To be read in conjunction with A Self-Guided (History) Tour of Muzium Negara

MURALS

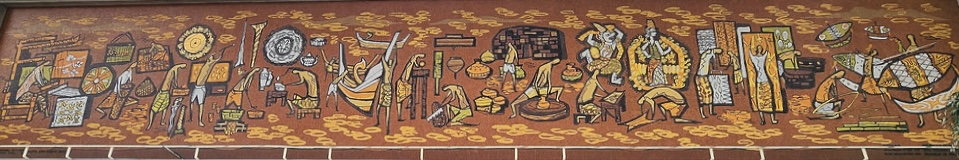

The sweep of Malaysia’s culture and history is emblazoned across the front of the National Museum in the form of two massive murals flanking the main entrance. The murals are made of glass mosaics from Florence, Italy. The artist, Datuk Cheong Lai Tong, created the murals in 1962 after winning a competition commissioned by Tunku Abdul Rahman, Malaysia’s first Prime Minister. The two murals are titled Episodes of Malayan History (the East Mural) and Malayan Crafts and Craftsmen (the West Mural). You’ll notice that they are labelled Malayan, as Malaysia only came into being in 1963.

West Mural: Malayan Crafts & Craftsmen

The West Mural highlights crafts that are synonymous with Malaysian culture. Handloom weaving of songket fabric is shown on the left end of the mural. This traditional craft involves inserting silver or gold threads to create motifs while weaving silk or cotton fabric. The craft, which goes back to the 13th–14th century, comes from Terengganu. The mural goes on to depict more weaving scenes, but this time of mengkuang (screw pine) leaves, bamboo or rattan to create baskets, bags and mats.

Next, metal crafts are shown, starting with two figures forging metal to create metal objects, including the keris (Malay dagger) and brass gong. Crafting of the keris is almost a sacred art. Next to this, two silversmiths are at work, one smelting silver and the other crafting silver objects, which include jewellery, teapots and vases.

Gallery A: Prehistory

The beginnings of culture took root in prehistory, as seen from the tangible remains from that time. Even as culture evolves with time, tenets such as a sense of community and adventure, the search for spirituality and connection, and innate adaptability and curiosity endure into the modern world.

Cave drawings

A common discovery from prehistory around the world is cave paintings or cave art. Cave paintings are time capsules that tell a story across millennia about early humans’ way of life, thought processes and environment.

The earliest known cave paintings in Malaysia are found in Gua Tambun, Perak, and Gua Kain Hitam in Niah, Sarawak. Believed to have been drawn c. 2,000 years ago, the paintings are of animals, geometric designs and symbolic boats. More recent cave paintings in Gua Badak in Lenggong, Perak, were drawn by the Orang Asli communities to record life during the British colonial period. Other cave paintings discovered were paintings of a group of men and women gathering. The red and black pigments are derived from hematite and charcoal, respectively.

Cave paintings have several cultural significances. It shows the early human’s ability to express themselves in abstract and creative ways—the earliest art form before Picasso and Monet were even born. Cave paintings of deer and dugong, discovered in Gua Tambun in Perak, give us insights into other creatures alive then and the game animals hunted for sustenance. These paintings could be part of rituals and practices to revere elements of nature, wish for bountiful hunts/harvests and remember the dead, suggesting a belief in animism, the supernatural and the afterlife. Or it could simply be a record of the day-to-day life of the ancient painter. A picture is worth a thousand words, indeed!

Dongson drum

What is now an ancient village in Thanh Hoa Province, Northern Vietnam, and presently home to 330 households, used to be the site of the Dongson culture, which spread its influence to other parts of Southeast Asia. One of the most recognisable artefacts from the Dongson culture, which existed between the middle of the first millennium BCE to the 3rd century CE, is the Dongson drum.

The drum, found throughout Southeast Asia with the possible exception of the Philippines, is made from bronze and easily identified by the bulging star at the centre of the tympanum. The star has an even number of rays, between 8 and 16. Other decorations on Dongson drums are motifs of animals such as deers, buffaloes, stylised forms of birds, humans engaged in various activities and geometric designs.

The Dongson drum’s presence in many parts of Southeast Asia is a testament to the interaction of cultures and communities in this region through trade. It is believed to have made its way across the mainland down to Peninsula Malaysia through riverine networks. Eight such drums were discovered in Malaysia at several locations in Selangor, Terengganu and Pahang.

The Dongson drums are believed to have been status symbols. Only the wealthy could afford to own them. The drums were buried with the owner or passed down to descendants as family heirlooms. Apart from that, the drums may have been used to summon ancestor spirits during feasts and ritual sacrifices, appease nature spirits residing in rocks and trees in animistic practices, induce rain in ritual dances in farming societies and may also be used during battles between warring factions.

No matter what the Dongson drum was used for in the past, its eye-catching beauty and uniqueness have been well-preserved over the centuries. Apart from being a tangible relic of the ancient Dongson culture, the drum also tells a story of the cultural and socio-economic realities of centuries past.

Megaliths

Megaliths are structures made of huge slabs of rocks, either standing alone or clustered with other stones. Like cave drawings, megaliths are found in different parts of the world. The megalithic site of Pengkalan Kempas is located near Linggi, Negeri Sembilan. The locals call the megaliths ‘living stones’ or ‘batu hidup’ because these stones appear to grow taller by one or two inches every year. The reality is less fanciful—it is due to soil erosion. As time passes, the soil at the base of this megalith is worn away by wind and water.

The rocks comprise three megaliths—the Rudder, Spoon and Sword, so named for its shape. The Rudder contains images of a four-legged creature, possibly a horse, and a bird, possibly a peacock. Its top resembles either an elephant trunk or a lotus stem and flower. The Sword, as its name suggests, rises to point skywards. Archaeologist I.H.N. Evans speculated that the Arabic inscription for ‘Allah’ carved between two lines at the top of the Sword records circumcision practices in Islam. The Sword’s mid-section is decorated with motifs that are the subject of differing interpretations—an ancestor stone of a face with a protruding tongue used to ward against evil and Hindu symbols of Vishnu, Kala head and lingam. The Spoon is undecorated but shaped like a rudimentary Hindu yoni. It may have been place beside the lingam-shaped Sword.

Studies on the megaliths show that Islamic, Hindu and ancestor motifs were carved in the same, albeit undetermined, period. This points to a coexistence of different cultures and practices within a local community, likely made possible through trade with foreign merchants. Visiting merchants arrived with their own beliefs, religions and practices, influencing the native beliefs and mores to create a unique blend of culture.

The megalith is currently part of an early Islamic grave complex near the tomb of a 15th-century “saint”, Ahmad Majanu. Its original purpose and creators are unknown. It was likely a sacred ground for the community that lived nearby for generations, an important location for the community to gather for rites and ceremonies—whether in celebration of life, mourning of death, or praying for good tidings.

There are more questions than answers for now. What is clear is that these stones from an earlier time speak to our search for meaning, a sense of community and belief in spirituality.

Buddhagupta Stone

The written script is one of human history’s most significant cultural developments. It is a means of communication to disseminate information and ideas, record history and events, and tell an interesting story. Each region develops its writing system at its own pace. Southeast Asia developed its written script later than India and China. Enabled by trade contacts, written records are kept of another culture that has yet to develop its own written language. The Buddhagupta stone, discovered in Seberang Prai, Penang, in 1834 by Captain James Low, is one such instance. The piece in the museum is a replica of the protohistoric stone; the original is at the Indian Museum, Kolkata, India.

The stone stele was donated by Mahanavika Buddhagupta to a local shrine. Buddhagupta was a Buddhist seafarer who lived in 400 AD and visited the northern Malay peninsula. The stone stele contains karma and gratitude verses inscribed in Sanskrit using the Pallava script.

Until the 7th century, there was no written script in local languages. As the region made more contact with foreign traders and travellers, the Malay language came to be written in Pallava script. Later, local versions of these scripts, including Kawi and Rencong, were developed to write the local languages. These scripts were popular until the early 13th century.

With the widespread adoption of Islam and close contact with the Islamic world, written Malay gradually evolved away from Pallava, Kawi and Rencong. The Quran, Islam’s holy book, was written in Arabic letters. The Jawi script was introduced to portray specific phrases more accurately. It is derived from the Arabic script but with six additional characters to reflect Malay pronunciation.

As trade boomed, Malay and Jawi became the lingua franca of this region, used widely by monarchs, officials and commoners. After Portugal conquered Melaka, the Jawi script became less popular. While not definitive, records exist that Malay was Romanised as early as 1516. The Malay language changed with different colonial powers adopting different spelling systems (Wilkinson for Malaya and van Ophuijsen for Indonesia). A Malay scholar, Zainal Abidin Ahmad, also known as Pendeta Za’ba, is credited for modernising the Malay language by publishing a series of Malay grammar books, “Pelita Bahasa”, in 1936.

Kuala Selinsing

First excavated by I.H.N. Evans in 1928, the Kuala Selinsing settlement is a riverine community that existed contemporaneously with the Bujang Valley civilisation. Located on the fringes of mangrove swamps at the mouth of Selinsing River, the community is believed to have occupied the area between 200 BCE and 1,000 CE. Homes were constructed on stilts using wood and thatch over small mudflats. The settlement’s location was marked with mounds composed of shells and earth. The mounds resulted from the accumulation of refuse discarded from the dwellings.

Excavations have yielded much insight into the Kuala Selinsing settlement. Beads made from semi-precious stones and glass, glazed wares, cowrie shells and earthenware pottery were among the artefacts discovered. Based on wasters, undrilled and partially drilled beads and chunks of coloured glass, researchers believe that the beads were manufactured onsite in Kuala Selinsing. The Kuala Selinsing settlement may have also served as a feeder port for local products collected from the hinterland, such as forest resins. Bujang Valley could have acted as the export hub for Kuala Selinsing’s beads after it developed into an entrepot.

The bones of deep-sea fish on site suggest that the people at the Kuala Selinsing settlement were likely seafarers. Despite interactions with Bujang Valley, which practised Hindu-Buddhism, researchers believe the Kuala Selinsing settlement practised animism. Unearthed burials contained skeletons buried in an extended position and grave goods such as beads, pottery, stone ornaments and food. Even in later periods, the dead were properly buried.

The Kuala Selinsing settlement was believed to be abandoned after 1,200 years of continuous settlement. Economic and geographic factors may have caused the people to leave the area.

Burials

There is a saying that nothing is certain except death and taxes. Death is a time of mourning and sorrow for those left behind, but it also marks the start of the deceased’s journey into the spiritual world. Many cultures worldwide today have different rituals and rites that started in prehistory.

The burial ritual with funerary goods or grave goods has its roots in prehistory. Grave goods have been discovered alongside prehistoric graves in Malaysia as early as c. 10,000 years ago. The ritual is based on the belief in an afterlife. The dead are buried with items used/consumed while they were alive, such as stone tools, shells and food as discovered buried with the Perak Man, or beads, glass and iron tools accompanying the Bernam Valley cist-slab graves. Grave goods indicate the social status of the dead; more elaborate goods often suggest someone from a higher social hierarchy.

Findings from the Niah Cave prehistoric graves indicate the development of discrete burials from c. 10,000 to 5,500 BCE, which signified a changed perception of death and cultural attitudes towards its appropriate treatment. This period also saw the creation of ancestral identities as communities buried their dead in specific localised groups.

Skeletons from before the Neolithic Age were mainly found buried in a flexed position. The flexed position, where the body is laid on the side or the back with knees bent close to the chest, is a common burial practice in Southeast Asia before the Neolithic Age. Skeletons buried in an extended position at Gua Harimau in Perak were said to be from the early Neolithic Age. There is no definitive explanation for the different burial positions. Hypotheses revolve around social status, age, and sex, as well as the influence of burial practices of other cultures interacting with the native culture.

In Malaysia, there were several types of burials, namely cist-slab burials, log burials, jar burials and Dongson burials, uncovered in different regions in the country:

-Dongson burial—The Dongson burial discovered in Kampung Sungai Lang in Selangor can be traced to the Bronze Age in Malaysia (c. 600 BCE to 200 CE). Two Dongson drums, originating from Dongson in North Vietnam, were found among the grave goods, such as earthenware bowls and glass beads. It is the only such burial found in Malaysia. This grave may have been a boat burial, considering the planks covering the grave are similar to wood used in boat making.

-Cist-slab burials—These are found in several locations in Bernam Valley Perak. Constructed from undressed granite, these graves were likely the burial sites of the elite who lived in riverine communities near the Bernam River during the Iron Age (c. 300 CE until 1,400 CE). It would have taken considerable manpower to construct the graves—from extracting the granite from the foothills of the Main Range, transporting it downstream to the burial sites and the actual construction of the grave. Funerary goods such as glass, beads, and iron tools were found inside and outside the graves.

-Log burial—Log coffins have been discovered in limestone caves in Sabah. The log coffins were made from local hardwood harvested from the rainforest, like Belian or Merbau. The log coffins discovered in the Sabah limestone caves were dated as 1,100 years old. It was also said that these coffins, with their handles decorated with animals such as snakes, buffalo, crocodiles or bird heads, were used to bury the elite. Grave goods such as weapons and food have been found around log coffins.

-Jar burial—Jar burial is a secondary burial practice in which the remains of the deceased are interred in jars with the bones after the body has been allowed to decompose elsewhere. Practised mainly in Borneo, burial jars discovered in Niah Caves were said to be from the Metal Age. The jars were locally made terracotta urns, but the usage of martabans and Chinese jars became prevalent later.

Gallery B: MALAY KINGDOMS

The emergence of the Malay Kingdoms in the 2nd century CE was a significant historical event that shaped the region’s cultural landscape. These kingdoms, spanning Borneo, Java, Celebes, the archipelagos of the Philippines and Indonesia, and parts of Indochina, established trade relations with China and India. This led to the growth of some kingdoms into large empires, thus expanding their influence. A significant section of this gallery highlights the glory of the Malay Kingdom of Melaka in the 15th century, a pivotal period that contributed to the formation of present-day nations across the region.

The cultural aspects of the Malay Kingdoms, including people, their beliefs, festivals, entertainment, and traditions, were naturally shaped by the historical events that took place there.

Pintu Setul

Gallery B invites you to step into history through the 120-year-old Pintu Setul, a door panel from a former palatial residence in Setul, southern Thailand, bordering the northern Malaysian state of Kedah. This teak wooden panel, built between 1843 and 1909 during the Kedah Sultanate, uniquely blends traditional Malay and Javanese designs, symbolic of the region’s rich cultural heritage and royal traditions.

Floral motifs cover the entire span of the door panel, giving the otherwise plain wood a decorative effect. Islamic art is typically presented through non-human representations, showcasing abstract or geometric designs, floral, fauna, the cosmos and calligraphy.

The carvings on the Pintu Setul reflect a rich tapestry of cultural heritage, incorporating influences from ancient traditions. In the Malay Kingdoms, a diverse blend of Hindu-Buddhist civilisations, Islamic art and colonial history led to captivating carvings produced by skilful local artisans. The process involved tearing the surface of a board or piece of wood to carefully design and carve out a motif, which can be superficial or penetrated through the entire thickness of the wood. These carvings, commonly found in wood and stone, as well as other materials such as metal and ivory, are aesthetic and functional, allowing ample daylight into the interior spaces or serving as light filtering devices to provide shade.

Such ornate carvings reflect the craftsmanship and cultural identity of the region. In modern times, wood carving is still prominent for cultural use in places such as Penang, where Chinese artisans would carve wooden signboards, ancestral tablets and furniture. The motifs used in woodcarvings play a significant role in conveying the cultural and social values of the community as well as enhancing our understanding of its traditional art amidst modern art.

Dragon Head

After passing through the conspicuous Pintu Setul, a coloured dragon’s head stands majestically on the left-hand side of the gallery. This dragon’s head is over 100 years old, and in the late 19th century, it was used as a prow on a traditional boat owned by the royal family of Pahang, an East Coast region of Peninsular Malaysia. Intricately carved from the wood of a jackfruit tree and suitably painted in vibrant colours, this dragon has carvings of bean tendrils that delicately intertwine with other detailed elements, showcasing the high level of craftsmanship by the artisan. The dragon’s head was believed to protect and guide the seafarers during their unpredictable journeys where maritime trade was vital to the culture and economy of the Malay kingdoms such as Srivijaya and Majapahit.

The cultural significance of dragons in the Malay Kingdoms provides a fascinating view of their effect on the people and their beliefs. In ancient Malay culture, which has roots in Hinduism and Buddhism, dragons are called naga, representing their physical form as a serpent or dragon-like creature residing in water or caves. The naga is commonly regarded as a symbol of fertility, protection, wisdom and auspiciousness.

The tranquil Lake Chini, located on the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia, Pahang, is thought to be inhabited by a naga called Sri Gumum that protects its flora and fauna and holds stories about an ancient sunken empire. The legend of Lake Chini holds cultural significance for the Orang Asli (original people in Malaysia) community, which reflects their strong spiritual connection to the natural environment and their deep beliefs about the spiritual forces attached to it. Similarly, other parts of Indochina have versions of legends and folklore around dragons, highlighting this mythical creature’s deep spiritual meaning and profound symbolism.

In Malaysia, Islamic principles modified ancient ideas, expressing them through floral motifs over forms of animals and humans. However, some dragon ornaments are preserved and exist symbolically, such as dagger hilts, often used in traditional ceremonies. The rich heritage of dragons is still celebrated and preserved in present times through religious and cultural festivals and maritime events.

Spices

Melaka, located in the southwest of Malaysia, prospered in the 15th century as a port city for trading spices, textiles, and pottery, among other trade items, due to its strategic location in the Straits of Malacca, one of the world’s busiest shipping routes. The influences of these trade activities bestowed Melaka town with a multicultural heritage that is still alive today.

Spices were among the high-value products exchanged with foreign traders, and spices gave birth to a vibrant culture of unique cuisines in this region. The rich and diverse array of spices, which included pepper, cinnamon, mace, cloves and nutmeg, was highly sought after due to their high commodity value, medicinal properties, and tantalising fragrance for perfumery. The rich and diverse array of spices is also used in cooking various cuisines, with each ethnicity combining different spices to produce signature dishes representative of that community.

The multicultural setting of Melaka, with the influx of foreign and local traders, gave rise to the Peranakan (local-born) communities, which came from the descendants of intermarriages between foreign migrants and local women. These minority mixed-race communities each have their own lifestyle that is culturally unique from Malaysia’s main ethnic groups, as they are a hybrid of various cultures.

The Baba-Nyonya (Chinese Peranakan) cuisine uses spices like turmeric, lemongrass, galangal and peppers, resulting in a vibrant set of exquisite dishes from the merging of herbal elements of Malay cooking with the intricate flavours and Chinese cooking techniques. One of the signature dishes of Baba-Nyonya cuisine is ayam pongteh (chicken braised in fermented soybean paste), which utilises ginseng, ginger, star anise, lemongrass and cinnamon, among others, to showcase the complexity of this unique culinary style, which has stood the test of time for its delicious combination of flavours.

The Chitty (Indian Peranakan) people originated from South India and adopted Malay and Chinese cultural practices while retaining their Hindu faith. Their culinary heritage is a unique blend of South Indian and Malay cuisines. Common wet spices used to prepare Chetti culinary staples like pindang are lemongrass, galangal, and turmeric, ground into a fine paste and simmered in thick coconut cream that cooks the wolf herring fish. This is in contrast with Indian cuisine, which is widely known for the use of spice mixes made from dry spices.

Cuisines from Indonesia and Malaysia prominently incorporate aromatic spices such as cardamom, cinnamon, and star anise to prepare rendang, meat that is slowly stewed in coconut milk and spices for hours.

Spices are essential in Asian cooking and for traditional wellness and healing. Traditional remedies with spices are still regularly practised in many local communities. These include aromatherapy ointments made from lemongrass and cloves, Traditional Chinese Medicine, Ayurvedic medicine, and Jamu (Indonesian traditional medicine). From the era of the Malay Kingdoms to the present day, spices were not simply commodities but helped to shape the economy and influence culture and societal structures. The spice trade generated wealth in the Malay Kingdoms, where cities like Melaka became active trade and cultural exchange hubs attracting global merchants, travellers and scholars, further contributing to the development of maritime empires in the region and leading to diversity that is reflected in contemporary Southeast Asian societies coexisting and influencing each other.

Rebab

Every region in the Malay Kingdom has its musical concept as part of community entertainment. Trade routes from East and West introduced a mix of musical instruments and folk music from the Arab world, China and India. Apart from being a mere tool of entertainment, music, in general, offers a healing and therapeutic experience to the performer and its audience. The gamelan is a traditional orchestra originating in Java.

A fiddle instrument known as rebab is part of the gamelan orchestra. Like the traditional Chinese instrument erhu, the rebab is played by friction of a bow against the two strings attached to the instrument’s body. The craftsmanship of skilled artisans is reflected in the meticulous construction of the instrument, which is made of wood, horsehair, buffalo bladder, or gut and completed with intricate decorative carvings.

On the east coast of Malaysia, the rebab accompanied ancient healing traditions conducted by a shaman that included trances and rituals, making it a mystical instrument. It is one of the main instruments played in Mak Yong, a dance drama from southern Thailand that initially incorporated animistic practices into its performance and, later, Hinduism, Buddhism and Islamic influences.

Whether these performances are staged in villages or sophisticated urban settings, a strong connection exists between ritual and entertainment. These noteworthy connections involve the stories of legendary princes and princesses, ritual activities as displayed in the opening and closing sections of the performance and the ceremonial activity of mengadap rebab. The latter pays homage to the rebab and is an obligatory opening dance of every Mak Yong performance. It has symbolic and spiritual meanings connected to its ultimate teacher, who remains unnamed to protect the sensitivities of this idea.

Other roles of the rebab can also be witnessed in Main Puteri, another form of healing performance that aims to cure patients bearing emotional or spiritual illness, and the shadow puppet theatre, where the esteemed rebab not only acts as a melodic accompaniment but also enhances dramatic effect by interacting with the shadow puppeteer.

The rebab is of significant cultural importance in the Malay Kingdoms of Southeast Asia. It continues to be part of traditional Malay cultural heritage through ritual accompaniment, courtly ceremonies and public entertainment.

Keris

The keris is a Malay defence tool, along with the spear, sword and dagger. Tucked at the waist, it used to be a companion of every Malay man, as it accompanied the wearer everywhere. The keris worn by royalty, nobles, and warriors have distinguishing features that display the status and lineage of the wearer; for example, the number of luk (waves) on the keris distinguishes royalty from commoners.

The earliest-known keris dates to the 9th century, a carving on Borobudur. However, some researchers opine that Vietnam’s 3rd-century Dongsonian bronze culture influenced its manufacturing technique. Naturally, the use of the keris spread to the entire Malay Archipelago. Due to its multi-function, aesthetic arts, and philosophy, the status of the keris as a weapon is elevated to the highest level in Malay civilisation. At the same time, its significance is attached to the identity and dignity of the Malays.

This Royal Keris of Celebes has a sword-like wavy blade. Its hilt is made of carved ivory neatly wrapped by a copper band at the base. The crosspiece of the sheath is also made of ivory, and the gold sheath itself has intricate carvings of bean tendrils. Altogether, the keris and its sheath measure 43cm long and 10cm wide.

Apart from its purpose for self-defence, general protection and daily cutting tasks, the keris was also used as a ritual offering for the supreme being, as amulets for protecting oneself or the family, and for one’s good fortune. In modern-day times, the keris is a ceremonial item at the courts of royal families and is worn as part of the traditional Malay wedding attire.

Hang Tuah

One of the most prominent spots in this gallery is a towering mural of Hang Tuah, the most famous warrior and admiral in Melaka.

Based on the Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals), Hang Tuah was born in the 1430s and is celebrated as the greatest master of silat, a traditional martial art form in the Malay Kingdoms. In this artist’s depiction of Hang Tuah, he dons a complete customary Malay ensemble. One of his prized possessions was a keris named Tamingsari. The seven-luk blade of the Tamingsari was made from several types of iron that possessed magical and mystical properties, believed to supply its owner with invincible power. Revered for his loyalty, courage, and relentless dedication to Sultan Mansur Shah and his country, his legendary status has been recorded in several works of literature and brought to life in cultural performances.

Carved across the top of this mural is “TA’ MELAYU HILANG DI-DUNIA”, which means that the Malays shall not vanish from this earth. This symbolises the bravery of the Malays during the golden age of Melaka.

His epic adventures emphasise traditional Malay values of loyalty, honour and integrity in fulfilling one’s duties and responsibilities, coupled with courage in the face of adversity. Across the Malay Kingdoms, his stories continue to inspire tales of heroism and resilience.

Despite available literary works swaying between the history and legend of Hang Tuah, he remains a cultural icon from the ancient Malay Kingdoms to present-day Malaysia. His lasting impact on literature, arts, and education, as well as being a symbol of unity in a multicultural setting while preserving Malay traditions, is a testament to his existence, transcending time.

Gallery C: COLONIAL ERA

Gallery C explores the Colonial Era in Malaya, which lasted over 450 years and was marked by consecutive influences from Portuguese, Dutch, British, and Japanese rule. Each colonial power brought the culture of their home countries to the Malay world, shaping the language, cuisine, architecture, and societal norms of the local culture; their influences continue to be felt today.

Portuguese Rule

The Portuguese era in Melaka, which spanned 130 years, left an indelible mark on the region’s history and culture. The influence of Christianity became prominent, shaping religious practices and beliefs among the Eurasians in Melaka. This period also saw significant architectural developments, including the construction of forts and churches that still stand today as a testament to the enduring Portuguese influence, namely Porta di Santiago and St Paul’s Church.

The Portuguese settlers married local women, forming the Kristang community, a Portuguese-Eurasian community that continues to speak the Kristang language, a hybrid of Portuguese, Malay, and English. Celebrations like the Fiesta San Pedro and Intrudu Festival, featuring Portuguese dance and local songs like Jingkli Nona, remain integral to Melaka’s Portuguese cultural heritage. They foster a sense of communal joy and tradition.

The Dutch Rule

During the Dutch rule, the region experienced significant cultural changes. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) played a key role in the spice trade and governance, influencing local culture through architecture, language and daily life. The Dutch architectural influence is still visible in Melaka’s Stadthuys building.

Artefacts like the VOC’s cobalt blue and white porcelain plate, adorned with foliage, bamboo, and pomegranate motifs, were used as corporate gifts throughout their colonies, including Melaka. These plates symbolised the VOC’s branding and the power of its officers. The elaborately carved wooden armchair, featuring elegant motifs of flora, foliage and eagles, along with the use of local rattan, showcases a blend of Dutch and Javanese artistry.

The plate and armchair, adorned with natural motifs, were designed for people in positions of power. They underline the culture of status and authority prevalent during this period of colonial rule.

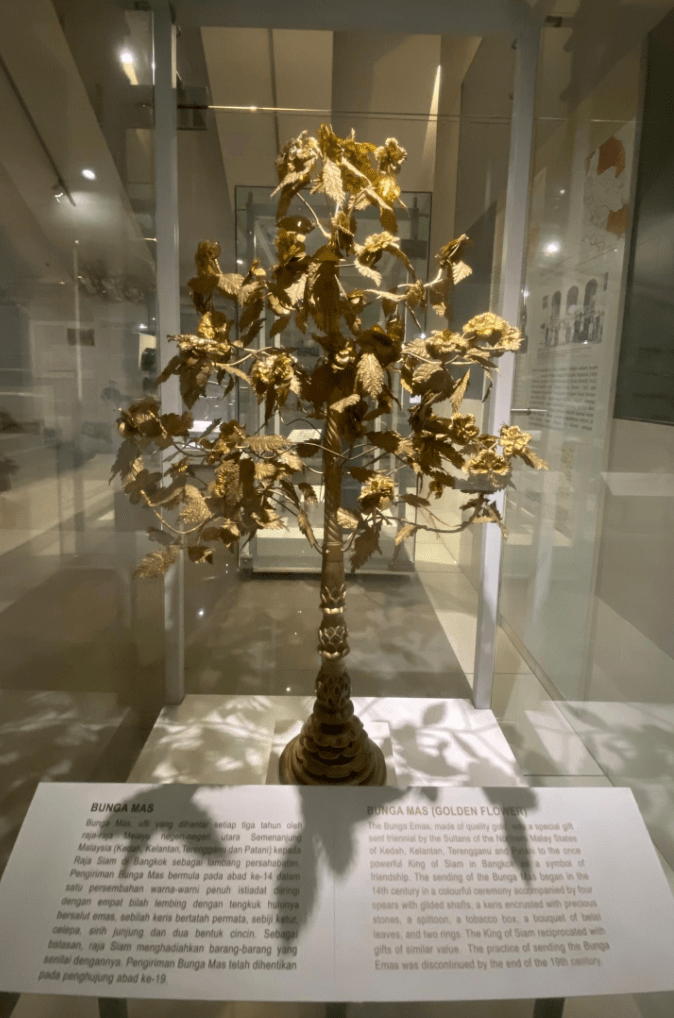

Bunga Mas

The Bunga Mas, or golden flowers, are beautiful decorative flowers made by expert Malay craftsmen using quality gold and silver. They were a traditional gift presented every three years to the King of Siam (now Thailand) by the rulers of the Malay states of Kelantan, Terengganu, Kedah and Pattani as a symbol of friendship and recognition of the Siamese king’s sovereignty. The exchange strengthened diplomatic ties and facilitated peaceful relations between the Malay states and Siam.

The last Bunga Mas from Kedah to the King of Siam was sent in 1906. In March 1909, the signing of the Bangkok Treaty between Britain and Siam resulted in the transfer of sovereignty over the northern sultanates of Malaya (excluding Patani and Setul) to Britain, altering the diplomatic and economic landscape of the region.

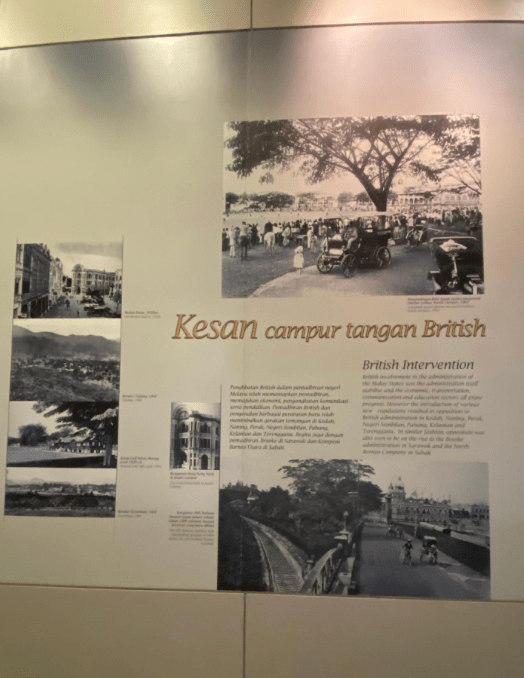

British Rule

The British introduced the process of formal agreements and treaties with governments, establishing a binding word of law. This laid the groundwork for Malaysia’s adoption of the legal commonwealth system, a legacy that remains a strong influence in the nation’s democratic rule.

On a lighter note, recreational sites at hilltops, known as hill stations, were established for officers and soldiers’ families to escape the tropical heat during British rule. A notable example is Fraser’s Hill. The tradition of enjoying English tea with scones and strawberries in the cool mountain air has endured. It is now a popular cultural getaway for local Malaysians seeking a respite from the tropical humidity.

Football match at the second Durbar, Kuala Lumpur, 1903

Sports and recreation, introduced by the British to the locals in the early days of the Colonial Era included tennis, cricket, golf, football and horse racing. In the late 19th century, sport as a leisure activity was mainly the preserve of the small European elite. The less privileged were too busy making a living, while the wealthy Chinese preferred to spend their off-duty hours gambling or smoking opium. The Malays, on the other hand, enjoyed sepak takraw (a game in which we kick a rattan ball in the air), wrestling and kite-flying.

Football has been a popular school sport since its inception and is still Malaysia’s most popular game. At the second Durbar, the Conference of Rulers, held in Kuala Lumpur in 1903, a team from the Victoria Institution played against a town team. The diversity captured in this photograph illustrates the multicultural and multi-ethnic fabric of early 20th-century Malaya. It gives us insights into the historical and social context of the time, understanding how colonial influences and local traditions merged to shape the cultural landscape of Kuala Lumpur.

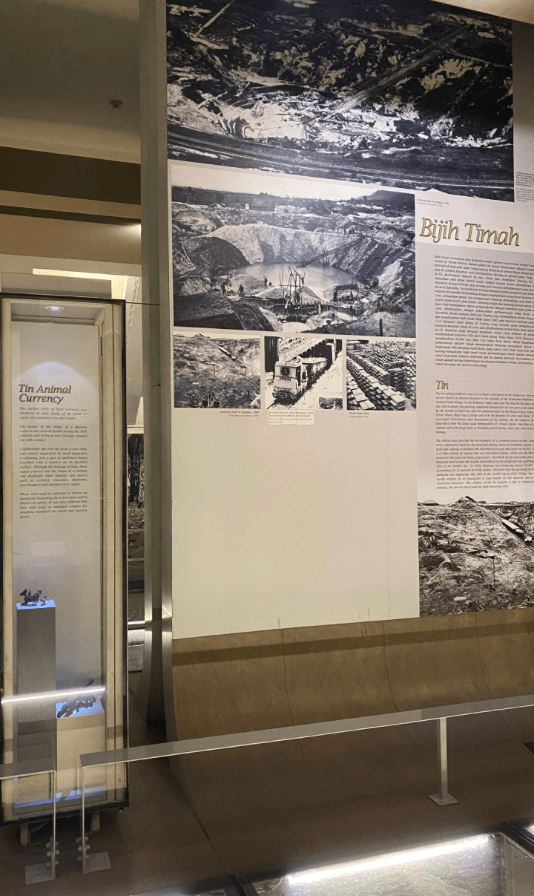

Tin Mining – Tin Animal Money

Tin animal money was the earliest form of currency used in the Malay Peninsula. These forms of currency were believed to have been used by the royal courts of the Malay Peninsular from the 15th century as gifts to royalty and for magical rites related to newly opened tin mines. It later evolved into a form of currency used in Perak, Selangor and Negeri Sembilan. These currencies were produced from solid blocks of tin metal or ingots and have animal forms such as tortoises, grasshoppers, cockerels, crocodiles and elephants. Animal money facilitated trade within the mining communities and with local merchants, serving as a medium of exchange before the widespread adoption of standardised coinage.

Rubber

Natural rubber has been the economic backbone of Malaysia since the industry’s early days, bringing prosperity to the nation. When Henry Ridley brought Brazilian wild rubber tree seeds to Malaya, he initiated an economically and socially significant industry for the country.

Mention rubber, and some people might recall the rubber tappers visible only by the glow of dynamo-powered torch lights and the crunching of dried leaves on the estate floor as they cycled between rows of rubber trees before dawn. These tappers play a crucial role in the rubber industry, utilising specific containers to collect and store fresh latex, the milky fluid obtained from rubber trees (Hevea brasiliensis). An essential tool for rubber tappers is the geredi (tapping knife), specifically designed for making precise incisions on the bark of rubber trees, and it continues to be used by rubber smallholders in Malaysia today.

Coconut and Rice

Coconut and rice hold multifaceted significance in Malaysian culture and daily life. They are a source of income, a symbol of hospitality, and play a central part in cultural rituals and traditions.

Coconut products like coconut milk, palm sugar and oil are integral to Malay and Peranakan cuisine and are rich in herbs and spices. The offering of coconuts in religious rituals like Thaipusam, whereby coconuts are smashed during this celebration, as the coconut symbolises the ego and shattering the ego exposes our inner spiritual purity, an act of humility.

Rice is the staple food, central to many dishes and cultural traditions. It is enjoyed by Malaysians of all ethnic backgrounds, making it a unifying symbol of national identity. The communal aspect of sharing a nasi lemak, rice cooked with coconut milk, further strengthens social bonds among family and friends. Rice holds a central place in the economic, culinary, social and cultural fabric of Malaysian society, reflecting its importance as both a dietary staple and a symbol of cultural heritage and identity.

Gallery D: MALAYSIA TODAY

Trade and travel have always contributed to Malaysia’s multicultural makeup. From discoveries in ancient sites to the country’s current globalised centres, it is clear that Malaysia today is not very different from the past in respect of its role as a centre of trade and migration.

The current demography in Malaysia’s society was accelerated by the socio-economic development during the Colonial Era. Labour-intensive economic activities like tin mining and rubber planting necessitated the importation of labour from India and China by the British to Peninsular Malaya and, to a lesser extent, Sarawak and British North Borneo (Sabah). Migration and settlement, as well as the creation of the Federation of Malaysia, resulted in a multi-ethnic society that is diverse in its culture, as seen through its languages, customs and practices, beliefs and religions.

Education & Languages

According to the website Ethnologue, almost 140 languages are spoken in Malaysia. Article 152 of the constitution states that Malay is the national language but also provides that “no person shall be prohibited or prevented from using (other than for official purposes), or from teaching or learning any other language.”

Although initially not standardised, Malaysia’s national education system structure is now well established, and the medium of instruction is Malay. However, there are also vernacular schools that provide instruction in Mandarin and Tamil, schools that teach Malay using the Jawi script, schools that provide lessons in Iban, and so on. In addition, there are also private and international schools. A common implement used by teachers of yesteryears was a rotan, a long, thin cane used for maintaining discipline. Those were the days when capital punishment was the norm!

Malaysians also speak various dialects—for instance, there are regional variations to the Malay language from North to South, East to West of Peninsula Malaysia. While using standard ideogrammatic writing, Chinese can be read according to dialects spoken by various Chinese subgroups, such as Mandarin, Hokkien, Cantonese, Hakka and Hainanese, to name a few. Similarly, the Indian subgroups in Malaysia also speak Hindi, Bengali, Telugu, Malayalam, Punjabi, etc. Print and broadcast media also reflect this mix with print papers in Malay (both in English and Jawi alphabet, English, Mandarin and Tamil) and TV/radio channels offering a variety of shows in the various dialects.

Malaysians often use a mix of languages in a sentence—affectionately termed Manglish or “rojak” language after a local mixed salad. Many terms have come into everyday use with meanings slightly different from their original definition. However, they are universally understood locally!

Communications

With education and improved literacy, print and broadcast media grew concurrently. Newspapers and other publications were printed in a number of languages. The growth in Malay journalism helped spur the growing consciousness of Malays to group and fight for the community’s welfare. These writings also championed the fight for nationalism. Radio broadcasting started with amateur wireless societies broadcasting in Johor, Kuala Lumpur and Penang. In 1934, the Penang Wireless Society broadcasted in Malay, Chinese, Tamil, and English. Radio Malaysia was established in 1946, but television services only commenced in 1963 with limited broadcast and, eventually, colour television was introduced in 1978.

Society

An overseas education meant a greater exposure to nationalist movements around the world. When these scholars came home, many served as teachers and writers and were in religious institutions where they could influence the masses. Hence, there was a growing political awareness among Malayans, which spurred nationalism. Self-governance was something to be aspired to. Political parties were formed, and campaigning commenced for the local Alliance Party to determine if it had the support of the people for self-governance.

Women played a great role in navigating grassroots work and spreading the word. As they moved easily in informal spaces—within homes, kitchens, and the like—they were able to pass on information regarding the fight for independence during moments of shared work or conversation. Political parties like UMNO had a women’s wing, which executed much of the home-to-home campaigning during elections. Women also played a role during the anti-colonial movement, whatever their ideology—some bearing arms, others spreading the word—all while playing their traditional roles in the economy, society and family.

During the Malayan Emergency from 1948 to 1960, many counterinsurgency measures had a profound effect on Malaysian society. The introduction of the Home Guards, National Identity Cards, and the establishment of New Villages shaped how society operated.

The spirit of gotong-royong—the communal obligation of individuals to their community and society—permeates all the different communities. This can be seen in the community coming together to ensure that the preparation for any celebration is shared or that the burden of any event, such as a bereavement, is lightened.

Merdeka—Celebrating Malaya’s Diversity

During the ceremony to proclaim Malaya’s independence, the Malay rulers attended in their traditional costumes. In their distinguished Malay suits made with the finest traditional textiles and wearing the tengkolok (traditional headgear), they were an eye-catching group.

The Merdeka celebrations in 1957 showcased the diversity of Malayans, with the different ethnic communities given the opportunity to showcase their cultural performances, ranging from dances to singing and stage performances. From the Sultans in their state finery to the performers in their costumes, the people of Malaya provided a colourful introduction to the country’s cultural diversity. The performances included the bangsawan, lion dance, asyik dance, Indian dance and singing by the Tres Amigos, a Portuguese group.

The States of Malaysia

A quick look at the flags and emblems of the different states of Malaysia offers insight into what the states were known for, be it a state flower, animal, or crop. Some states with Sultans also have an honorific Arabic name—beginning with ‘Darul’—while others, like Sabah and Sarawak, have honorific titles such as ‘Land of….’ Discover the different names by flipping the cubes!

Common Threads

These ten figures showcase a variety of costumes from a selection of communities in Malaysia. While the costumes are specific to certain ethnic groups, it is common for members of one group to wear the costume of another. Often, people have mixed lineage, which may not be readily apparent from their appearance.

From left:

- Male in a Hanfu/Magua—Chinese-style long tunic with a mandarin collar—worn over trousers. This is the male equivalent of the qipao.

- Female in a Baju Kebaya Labuh—traditional Malay dress with a long blouse generally reaching over the knee worn over a sarong.

- Female in Puteri Perak (Perak Princess) dress, distinguished by the use of trousers instead of a sarong. It is completed with a samping over the trousers and a selendang over the shoulder.

- Male in Iban warrior costume made with pua textile and headgear decorated with hornbill feathers.

- Female in a sari, tied in a Tamil Nadu style. This Indian garment comprises a short blouse, skirt petticoat and six metres of fabric wound round the body, with the ends draped across the body over one shoulder.

- Female in a Baju Kebaya Pendek, which is made from songket fabric. The top garment falls only a little past the hips.

- Female in a Chinese cheongsam or qipao, generally a long figure-hugging gown.

- Male in a KadazanDusun Penampang suit with a folded fabric headgear called a siga made from the dastar cloth

- Malay female in the style of Cik Siti Wan Kembang, a Kelantanese ruler. Note the keris that she is holding in her hand.

- Male in a Mengan top and Aceh-style trousers, commonly worn by male Kelantan rulers.

Beliefs & Religions

Malaysia recognises many cultural and religious celebrations by declaring national and state public holidays for them. The communities represented here include the Malays, Chinese, Indians, native people of Sabah and Sarawak, Baba Nyonya, Punjabi, Serani, Siamese, Orang Asli and Chitty. These groups practise religions like Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism, Christianity, Catholicism, Taoism, Buddhism and aboriginal beliefs, to name a few.

Some of the festivals celebrated are as follows, including the relevant greetings:

| Hari Raya Aidil Fitri | Selamat Hari Raya Aidil Fitri |

| Hari Raya Aidil Adha | Selamat Hari Raya Aidil Adha |

| Deepavali | Deepavali Valthugal |

| Chinese New Year | Gong Xi Fa Cai |

| Keamatan | Kotobian Tadau Tagazo Do Kaamatan |

| Gawai | Gayu guru, Gerai nyamai |

| Vaisakhi | Happy Vaisakhi |

| Loy Kratong | Sook San / Happy Loy Kratong Day |

| Wesak | Happy Wesak |

| Thaipusam | Happy Thaipusam |

| Christmas | Merry Christmas |

| Hari Moyang | Selamat Ari/Ayik Muyang |

Attending these festivals gives one an opportunity to experience the culture, especially the cuisine, and to gain insight into the various communities’ beliefs and rituals.