Focus Talk with Professor Dr. Masatoshi Sone

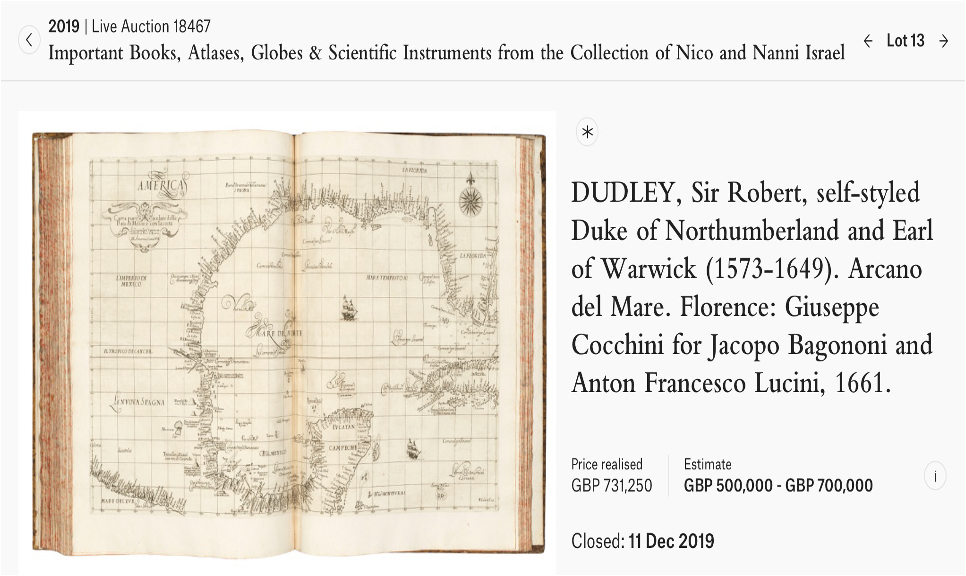

Written by Manjeet Dhillon

Introduction: Unveiling Lost Diversity in Borneo

At the MV Focus Talk series, the subject of the day was ‘Lost Diversity of Sundaic Borneo: New Findings from Sarawak.’ Our speaker was Dr. Masatoshi Sone, who shared insightful findings from his recent expedition where he spent a good ten days in the coal fields of Ulu Rajang looking for fossils. The talk began with an exploration of Sundaland, the name of the ancient continent that once included Borneo, Peninsula Malaysia, Sumatra, and Jawa Island. Geologically, Kuala Lumpur is situated in the heart of this vast continent.

Sundaland: A Fragmented Ancient Continent

About 11,000 years ago, this was one big piece of land. As sea levels rose, Borneo became separated from mainland Asia and other islands. The Wallace Line, named after Alfred Russell Wallace, a British naturalist who explored the region over a century ago, marks a transition zone between the distinct fauna of Asia and Australasia. This imaginary line runs from the Lombok Strait between Bali and Lombok in the south, all the way up through the Makassar Strait between Kalimantan (Borneo) and Sulawesi in the north. The islands on one side, like Sumatra, are mostly volcanic within a subduction zone with tectonic plates. This goes all the way to the east, including the Komodo islands, Timor Leste, Papua New Guinea, and Australia.

Plate 1: Wallace’s Line

Following Wallace’s Lead: Biogeography and Island Evolution

During his expeditions, Alfred Wallace, a naturalist with a keen eye for geology, noticed a peculiar phenomenon. Many animals, including birds of the same species, were present in Sumatra but seemed to disappear as you moved towards Lombok and the regions west of it. Wallace identified a significant biogeographic boundary between Bali and Lombok. Surprisingly, this invisible line had a profound impact on the distribution of various bird species. Many birds, it appeared, were reluctant to cross even the narrowest stretches of open ocean water. Essentially, Wallace believed that species change over time so they could fit into new environments.

This led Wallace to observe that in Bali, you’d find thrushes, woodpeckers, barbets, trogons, paradise flycatchers, paradise shrikes, minivets, blue drongos, pheasants, and jungle fowl, but colourful exotic birds were a rare sight. In contrast, in Sulawesi, Papua, and Timor, parrots, cockatoos, and lories were abundant.

The Wallace Line extends further between Borneo and Sulawesi, although this boundary is not visible to the human eye. However, animals seem to sense or perceive this invisible division. It’s important to note that Wallace’s discoveries were primarily based on biological observations (where he spent many years obtaining samples of birds, insects and animals) rather than in-depth geological knowledge of the islands. His research led him to a conclusion: animals evolve by adapting to their specific environments rather than by migrating to new ones.

Fueled by a passion to understand how new species arise, Wallace joined an Amazon expedition in 1848 (with Henry Bates). Sadly, a shipwreck in 1852 claimed most of their collected specimens. Undeterred, Wallace embarked on a groundbreaking Southeast Asian voyage (1854) that spanned eight years. His meticulous collection efforts yielded a staggering 125,000 specimens, including the iconic flying frog, and significantly advanced our understanding of the natural world.

A Glimpse into Earth’s Geological Timeline

Next ,we looked into the Earth’s geological timeline, which spans an immense 4.6 billion years. A particularly noteworthy period within this timeline is the Cenozoic era, which commenced approximately 66 million years ago. During this era, we witnessed the emergence of mammals and birds, along with the gradual evolution of primates and early hominids.

In the midst of the Cenozoic era (at the boundary between the Cretaceous and Paleogene periods), a large meteorite crashed into our planet, specifically in the area of the Caribbean Sea. This catastrophic impact spelled doom for the dinosaurs and many other species, opening the door for mammals to flourish and diversify.

As we consider Earth’s geological timeline, we find a key division between the Quaternary and Tertiary eras. This shift hinges on the transition from the Tertiary period, encompassing epochs like the Pliocene and earlier, to the Pleistocene and Holocene epochs of the Quaternary. This change mirrors significant shifts in climate, marked by a warming trend and rising sea levels. It’s also notable for the emergence of Homo sapiens, making it a pivotal juncture in our planet’s history.

Furthermore, the shift from the Pleistocene to the Holocene epochs indicates a transition from the last ice age, characterised by glaciers atop Mount Kinabalu. Interestingly, this transition aligns with Earth’s broader climatic cycle, suggesting that we’re gradually heading towards the next ice age in the grand scheme of geological time.

Plate 2: Geological Time Scale

Fossil Fuels: A Legacy of the Cenozoic Era in Malaysia

In the context of Malaysian geology, the Cenozoic period takes on paramount importance. This geological era witnessed the formation of numerous oil and gas (hydrocarbon) resources within the country. Throughout this time, a series of geological processes transpired, which included the accumulation of organic material and the creation of suitable conditions for the development of oil and gas reservoirs.

These developments have solidified Malaysia’s standing as one of the key regions for oil and gas production in Southeast Asia. Notably, substantial reserves can be found both onshore and offshore, underlining the nation’s significance in the oil and gas industry.

Borneo: From Sundaland to Fragmented Islands

Before the end of the ice age, Southeast Asia was part of a landmass known as Sundaland. This area connected many of today’s islands (Peninsula Malaysia, Sumatra and Borneo but also Java, Bali, parts of the Malay Peninsula, and other smaller islands in the region) into a single landmass due to lower sea levels caused by the extensive ice sheets.

As the Ice Age concluded, the rising sea levels, about 110 metres higher, submerged much of Sundaland, including the lowlands between the elevated regions of Peninsula Malaysia, Sumatra, Jawa, and Borneo. This flooding led to the formation of rivers like the Chao Phraya, Pahang, Pekan, Kuching, and Rajang rivers, which were previously part of the terrestrial landscape.

Sarawak’s Caves: A Treasure Trove for Prehistory

Looking at Sarawak, we have some famous caves such as Niah cave, and also Mulu. The caves in this region have been of interest to palaeontologists due to the discovery of prehistoric fossils and archaeological artefacts. These findings have contributed to our understanding of the region’s prehistoric past.

In archaeology, the Niah caves (Sarawak – discovery of skulls in 1958) and Madai caves (eastern Sabah), contain remains of prehistoric human activity, where Niah is famous with coffins together with animal remains, These caves also hold animal remains alongside human artefacts, otherwise for most of Sarawak there is no paleontological record. Evidence suggests human activity in the area began around 30,000 years ago. Fossils, including those of tigers and tapirs, have also been found. Notably, these animals are no longer present in Borneo, having disappeared naturally before human arrival.

The third largest city in Sarawak is Sibu, where we can journey along the Rajang River (longest river in Malaysia) to Kapit, a town located inland along the river. The Rajang river also flows in the general direction towards the largest dam in Malaysia, the Bakun Dam which is located on the Balui River (a tributary of the Rajang River). Here we now have two smaller rivers or tributaries merging with the Rajang River in Kapit, then continuing downstream towards the river’s estuary, where it meets the South China Sea. This is where the fresh water from the river mixes with the saltwater of the sea.

Plate 3: Rajang river basin

Unearthing Borneo’s Past: The Rajang River and Fossil Discoveries

The Rajang River’s characteristics stand out in contrast to typical slow-flowing and meandering rivers in Malaysia, where it is a straight course and fast flowing. This might be because it originates in or flows through areas with steeper terrain, where the river descends more rapidly. As it approaches Sibu, the river transforms into smaller channels, creating a delta structure. This delta is the product of sediment deposits and the river’s interactions with the sea. It provides a favourable environment for a notable population of large crocodiles, making Sibu their known habitat.

Here at this delta, many fossil remains have been discovered such as spines, fins or ribs of fish. Fossils are often found in black or brown hues, indicating they have undergone the fossilisation process including phosphatisation.

Island Endemism: The Case of the Bornean Banteng

Fascinating fossil discoveries in Sabah include the premolars of the Banteng or Tembadau in Malay (species: bos javanicus), a wild cow species, which we understand has been here before humans and during Sundaic time as well. Bornean bantengs are smaller due to a phenomenon called “insular dwarfism” or “miniaturisation.”, where island-dwelling mammals tend to evolve smaller body sizes over time (same applies for African elephants and Asian elephants). This phenomenon is a remarkable example of how isolated island environments can influence the evolution of species, leading to unique adaptations and characteristics. The Banteng is facing a gradual decline in Sarawak and is on the brink of extinction in Malaysia. Currently, Cambodia hosts the largest population, followed by Australia. It’s important to note that these populations in Cambodia and Australia are not native but were introduced by humans.

Plate 4: Banteng (wild cow)

Echoes of the Past: Fossil Tapirs and Their Relatives

Fossils of tapirs, identified as a type of metatarsal belonging to the extinct Tapirus sp., have been found in the Niah and Madai Caves. However, these tapirs are not directly ancestral to the present-day Malayan tapir. While they may have shared similar black and white stripes, these extinct tapirs inspired legends of a mythical creature that came through China and could eat our trees.

There are four species (four genus) of Tapirs in the world:

- Lowland Tapir (Tapirus terrestris)

- Baird’s Tapir (Tapirus bairdii)

- Mountain Tapir (Tapirus pinchaque)

- Malayan Tapir (Tapirus indicus)

Plate 5: Tapir

Today’s DNA studies confirm the Malayan tapir as the sole surviving Asian tapir species, with its closest relative being the American tapir. Evidence suggests tapirs originated in Eurasia, where they are now extinct. The split between Malayan and American tapirs likely occurred around 25 million years ago, predating the most recent ice age. This time frame coincides with periods of lower sea levels that exposed land bridges, allowing many mammal migrations like horses, sheep, and even some Asian monkeys to move from Eurasia to North America and eventually South America. While the tapir story might not directly involve the most recent ice bridge, it highlights how continental movements and changing sea levels have shaped the distribution of animals throughout history.

Extinct Tapir Diversity and Zooarchaeology

While the Malayan tapir is the only survivor in Asia, evidence suggests a greater diversity of tapirs once existed. A striking example comes from the Lubang Jeriji Saléh cave in East Kalimantan, Borneo. This prehistoric limestone cave, dating back to the Pleistocene epoch, features a large reddish-orange figurative cave drawing of animals. These depictions, alongside fossil remains like those of tigers now absent from Borneo, highlight the valuable role of zooarchaeology in reconstructing past ecosystems. By studying animal remains and artistic representations, we can gain insights into species that no longer roam these regions.

Plate 6: Cave drawing at Lubang Jeriji Saléh, East Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo

Uncertain Fossil Identity and Regional Rhino Extinction

Some fossils unearthed in East Malaysia reveal animal hooves that could belong to either tapirs or rhinoceroses. Unfortunately, differentiating between them solely based on hoof characteristics is challenging. Sadly, rhinoceroses are already regionally extinct in East Malaysia. The last recorded Sumatran rhinoceros in Sabah died in 2015, prompting the government to declare its local extinction. However, there’s a glimmer of hope. A small population of 10 to 20 individuals was discovered in East Kalimantan in 2016, highlighting the importance of conservation efforts for this critically endangered species.

Fossil Evidence of Sea Cows (Sirenia) in Sarawak

Aquatic mammal fossils, identified as sea cows (Sirenia) or dugongs, have also been unearthed in Sarawak. These gentle giants, related to manatees found in Central America and the Caribbean, once thrived in the coastal regions. They fed primarily on seaweeds. Sadly, sea cows are now locally extinct in Sarawak.

One key characteristic that aids in identifying Sirenia fossils is their density. Due to their composition of calcium carbonate, these bones are significantly heavier than most other animal remains. This weight factor alerted Dr. Sone’s team to the possibility of a Sirenia fossil upon discovery.

The Enigma of the Tambun Cave Dugong

The Tambun limestone cave in Ipoh boasts archaeological paintings, estimated to be around 5,000 years old, featuring an image resembling a dugong. This poses a fascinating puzzle considering the significant distance between the current coastline and the cave’s inland location. Further research, potentially involving geological studies and a deeper analysis of the cave paintings, might shed light on this intriguing mystery.

Plate 7: Tambun (Ipoh) cave painting: dugong

The Story of the Suidae Family and the Bearded Pig

The Suidae family, encompassing wild pigs and boars, boasts a global distribution across Eurasia, North Africa, and the Greater Sunda Islands. Evidence suggests their origin lies in Southeast Asia during the Pleistocene epoch (1.4 million to 11,000 years ago). From this ancestral homeland, they likely migrated outwards into other parts of Eurasia.

Wild Pigs of Borneo: Bearded Natives and Introduced Relatives

Borneo boasts two distinct wild pig species, both belonging to the genus Sus. The first, and likely more familiar, is the wild boar (Sus scrofa). While not native to Borneo, this species can interbreed with domestic pigs. The second, and truly indigenous pig, is the bearded pig (Sus barbatus). Fossil evidence, particularly differences in molar morphology, helps differentiate these two species.

Distribution patterns paint a clear picture. The common wild boar, also known as the Eurasian wild boar, dominates across Eurasia, with introduced populations in Australia and northern South America. In contrast, the bearded pig reigns supreme in Borneo, with a smaller presence in Peninsular Malaysia. Interestingly, fossils from the Niah Caves reveal no evidence of the common wild boar, only the bearded pig. This suggests that the wild boars currently found in Borneo were likely introduced by humans.

However, there’s a twist! Fossil discoveries in central Sarawak showcase the presence of both pig species even before human arrival. This intriguing find remains an active area of research.

Summary

Understanding Borneo’s rich biodiversity, both past and present, is crucial for informing conservation efforts and protecting this irreplaceable natural heritage. Dr. Masatoshi’s team is currently exploring fossils of a fly and plant fossils in a coal mine in Sarawak.

Reading material from MV Library

Here are some books that would likely be excellent reading material for further exploration:

1. Borneo Biodiversity: Tropical Rainforests from the Heart of Southeast Asia (ISBN 9789811073447) by Eric D. Wikramanayake, Michael D. Sorenson, and Thomas J. Conway

2. Island Biogeography: Theory and Conservation Practice (ISBN 9780691166488) by David Wright

3. A Field Guide to the Mammals of Borneo (ISBN 9789834280635) by J. Payne, C. Francis, and K. Phillipps

4. The Quaternary Period (ISBN 9780131174749) by John A. Quaternary

5. Encyclopaedia of Malaysia: Volume 4. Early History by Dato’ Nik Hassan Shuhaimi Nik Abdul Rahman

6. The Malay Archipelago by Alfred Russell Wallace