By Noriko Nishizawa, inspired by professor Dr. Farish A Noor’s talk on January 27th, 2024

Sir Thomas Stamford Bingley Raffles (1781-1826) by George Francis Joseph, 1817 (Source: National Portrait Gallery (London) )

When you google Stamford Raffles, the first sentence that you will most likely come across is, “Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (1781 – 1826) was the founder of the city of Singapore, and was largely responsible for the British Far East Empire”. That was my perception of him as well.

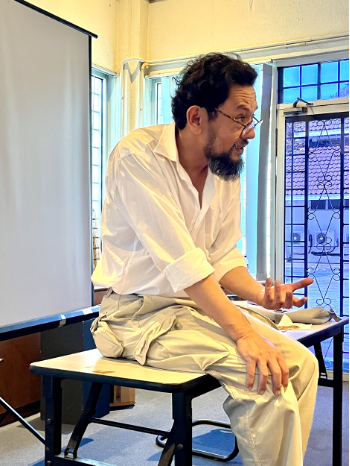

The talk by Professor Dr. Farish Noor to the museum volunteers on January 27 was very fascinating. He is a well-respected academic and is currently professor at the Department of History, University Malaya. Dr. Farish believes that the 19th century was the most important century as far as Southeast Asia (SEA) is concerned, because the construction of SEA during that century by the forces of capitalism and imperialism remains a potent aspect of political, economic, and cultural disputes in the region today. He told us that it is important to look at historical as well as institutional context to understand history. His talk focused on Stamford Raffles’ administration in Java, and he explained very interesting insights into why and how Raffles is recognized as a hero today.

Professor Dr. Farish Noor (Photo taken by Noriko Nishizawa)

He opened his talk, “Raffles in Java”, with a question: What makes Stamford Raffles special? His answer was “nothing”. Of course, he was exaggerating, but he wanted to make a point. He told us that when we look at Raffles in Java, historical and institutional contexts need to be taken into account.

First, we need to know about the historical background. The war for independence fought by the Netherlands against Spain became a commercial competition as well as a military and naval war. The United Dutch East India Company (VOC) was founded to operate and organize trade. The VOC became a chartered trading company and the first joint-stock company in the world. This was very significant because, throughout the European history of politics, the states were always dictated by kings and a handful of elites. For the first time, the Dutch citizens invested capital and sponsored the formation of the VOC which acted as an arm of the state.

The Dutch government granted the VOC the right to conclude treaties, build forts, maintain armed forces, carry on administrative functions in colonies, etc. The VOC became a trading colossus and is considered the world’s first multinational company. The success of the VOC sparked a chain reaction throughout Europe, and the English East India Company (EIC) was founded as well. This was the start of the middle class merchants gaining power and control.

Stamford Raffles came from a humble background and joined the EIC as a young man. Naturally, as Dr. Farish mentioned, the power vested in Raffles later, came not from himself, but from the mechanism of the institution (the EIC) that shaped British colonialism. He also said what was special about Raffles was that he understood well how the mechanism of the company worked. At the age of 14, he started working as a clerk in London for the EIC. Nine years later, he was sent to Penang. Raffles did not complete a formal education, but he studied science, natural history, and languages, since he had started at the EIC, which made him unique in the company. It didn’t take long before Raffles’ knowledge of the Malay language and their customs, as well as his paternalism and concern for the Javanese, helped him to become a protégé of Lord Minto, the governor-general of India. The British were given an opportunity during the French revolutionary wars to invade Java, when Prince William V of Orange requested Britain to take control of Dutch possessions until the wars were over. Raffles’ intellectual and administrative abilities played a large part in planning the capture of Java from the Dutch. Minto gave considerable credit for its success to Raffles and put him in charge. Raffles, at the age of 30, became lieutenant governor of Java; to administer the island of Java and govern over several million Javanese. Java was under British rule from 1811 to 1816.

Incidentally, the invasion of Java was controversial, and it was criticized by the British public. William Cobbett was a popular English journalist who played an important political role as a champion of traditional rural England against the changes wrought by British colonialism. Cobbett pointed out that the invasion of Java was not simply an extension of the war against Napoleon and his Dutch allies beyond Europe. He questioned if the rights of the natives of Java themselves were denied, and whether the British crown possessed the moral right to usurp power from the Dutch.

Nevertheless, Raffles suddenly possessed enormous power in Java. He inaugurated a mass of reforms aimed at transforming the Dutch colonial system and improving the condition of the native population. Raffles’ reforms were generally well accepted in Java. He introduced partial self-government. He also attempted to replace the Dutch system of forced labour and fixed quotas with a cash-based land-tenure system. As Dr. Farish explained, we must be aware that Raffles was a very modern individual with innovative ideas, who also became renowned for his outstanding liberal attitude toward people under colonial rule. As a result, Java was elevated in a few short years to a degree of liberty and prosperity. However, upon the Dutch’s return to power, Raffles’ reforms were phased out. The new government returned to the system of enforced labour, production restrictions, etc.

Raffles’ reforms, however, proved too costly to the EIC, which was primarily concerned with profit. His lieutenant-governorship in Java ended just before the Dutch came back to Java, after the Napoleonic wars ended. That became Raffles’ greatest disappointment in his life. Raffles was removed from his post by the EIC on account of poor financial performance, financial misconducts, and more. His reputation was tarnished.

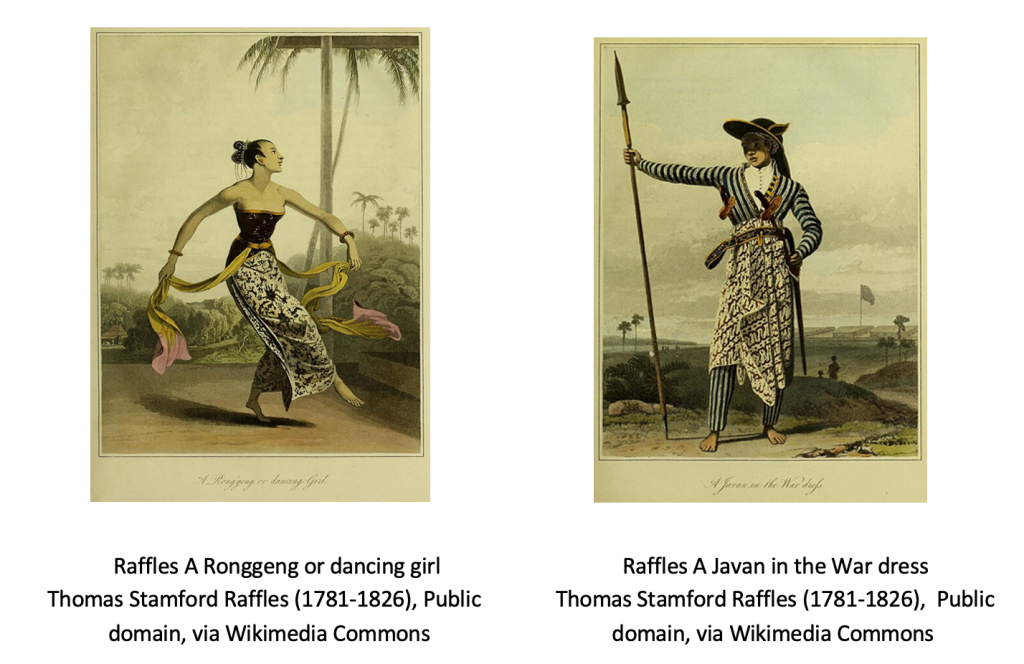

In order to reinvent himself, he wrote a book: The History of Java, that was published in 1817. The book (volume 1 and 2) contains plates depicting Javanese costumes, some describing language and music, others illustrating Javanese weapons, and one showing traditional masks and shadow puppets. Interestingly, the book is not much about the history of Java, but contains enormous information about the Javanese people and culture, which he had catalogued during his stay. His original motive to write the book might have been purely humanitarian, fundamentally favourable to the Javanese, but unfortunately, he was more concerned that his tenure as lieutenant governor of Java would be seen in a favourable light. In order to do so, he needed to show the British that he was capable of transforming these natives into a “civilized nation”. According to Dr. Farish, Raffles also had a typical colonialist view of this country when he said, “Java and the Javanese are a land of antiquity trapped in the past; therefore, they needed to be conquered in order to be rescued.” This wasn’t based on a political rationale. Dr. Farish explained that their culture was in a sense considered reductive and regressive. In fact, this colonial bias was the common sentiment and logic of colonialism during the 18th– 19th centuries.

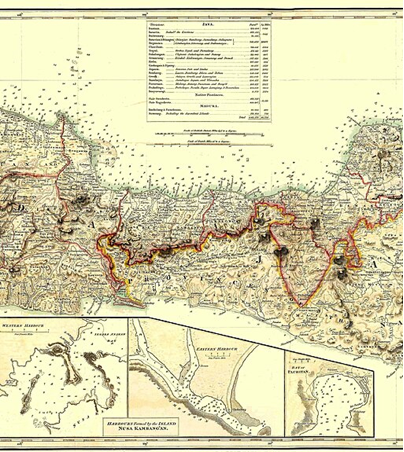

As previously mentioned, Raffles was a modern individual with innovative ideas. It was only during the British occupation of Java (1811-1816) that men like Stamford Raffles and John Crawfurd, who was appointed to the post of Resident Governor at the Court of Yogyakarta,would begin to compile vast information about the island and its people. Dr. Farish emphasized that Raffles’ idea of data collecting was actually a very modern technique. It could have been used as a powerful tool to maintain power/control over the people. Not many people at the time realized how significant that was. We could wonder what would have happened to Java if Raffles had stayed there longer. Incidentally, under Raffles’ instructions, ancient monuments such as Prambanan and Borobudur were catalogued and uncloaked out of overgrown vegetation by his officers. He had a large number of troops at his disposal, and he sent them out everywhere to collect information. Eventually, he succeeded in reintroducing himself as a scholar to the British public. He was invited to join the Royal Society, the leading body of scholarly investigation in early 19th-century Britain and was awarded a knighthood in 1817.

Thomas Stamford Raffles Map of Java (Central Java)

Thomas Stamford Raffles, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Although Raffles was sent back to the East by the EIC later; he became the lieutenant governor in Bencoolen, and also negotiated the right to establish Singapore, etc., these roles came with only reduced and restricted authority. He never regained the same status and glory that he had in Java. Due to his deteriorating health, he went back to England, and he died in 1826 at the age of 44. Then he seemed to be forgotten by the public for a few decades.

Dr. Farish continued to tell us that the story about Raffles didn’t end at his death, and it wasinteresting to see how history turns around in a very funny way. When England was at the peak of its power during the Victorian Era (1837-1901) the politicians and writers questioned Britain’s imperial systems and responsibilities. When imperial rule was seen to be done particularly well or particularly badly, it attracted considerable public attention, and this attention often focused on individual imperial agents. This Victorian mentality needed to create heroes as imperial agents to glorify the British Empire. As a result, Raffles was brought back as an icon of imperial colonization in the late 19th-century. He has been commemorated by statues, institutions and establishments were named after him, to solidify and justify a British presence in the region and larger imperial history.

Sir Stamford Raffles statue Singapore (Photo taken by Noriko Nishizawa)

Dr. Farish reminded us that although Raffles genuinely tried to help the Javanese and Victorians presented him as a hero, he had flaws that have to be looked at from a historical and institutional context. Today he is known as the founder of Singapore. Although his work in Java was short and he didn’t have a significant impact on its history, what Raffles tried to do in Java cannot be overlooked. He is remembered today because he was a true modern thinker for his time.

References:

Farish A. Noor, Anti-Imperialism in the 19th Century:

A Contemporary Critique of the British Invasion of Java in 1811 (2014)” https://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/WP279.pdf

Farish A. Noor, Where Do We Begin? Reclaiming and Reviving Southeast Asia’s Shared Histories and Geographies https://www.eria.org/ASEAN_at_50_4B.4_Noor_final.pdf

Natalie A. Mault, Java as a Western construct: an examination of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles’ “The History of Java” (2005) https://repository.lsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4005&context=gradschool_theses

Sir Stamford Raffles, Prosper Australia https://www.prosper.org.au/geoists-in-history/sir-stamford-raffles/#:~:text=Through%20his%20keen%20knowledge%20of,of%20some%20five%20million%20people.

Sir Stamford Raffles, Britannica https://www.britannica.com/biography/Stamford-Raffles

William Cobbett, Britannica https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-Cobbett-British-journalist

The History of Java Royal Collection Trust https://www.rct.uk/collection/1074474/the-history-of-java-volume-1