By Eric Lim

Introduction

As we all know, Federal Territory Day has been celebrated on 1 February every year since its inception in 1974 when Kuala Lumpur was transferred to the Federal Government. Of late, areas around Kuala Lumpur Chinatown have come under close scrutiny. Authorities have launched a security operation to curb the influx of foreigners to the area. The area is also affected by the increasing presence of homeless individuals and the worsening rubbish problem.

The relocation of the popular Pasar Karat / flea market to a new location which was supposed to have been carried out at the start of the new year has met with objections from traders of both locations.

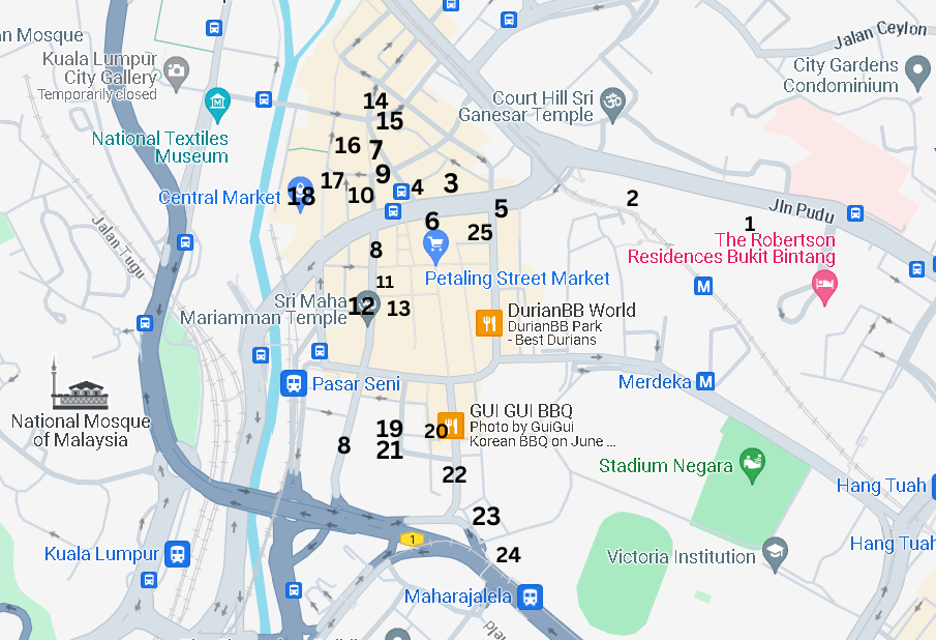

I had the opportunity to participate in an early morning walking tour covering the heritage sites in and around Chinatown, and probably get a first hand impression of the issues as mentioned above.

Construction site of Plaza Rakyat, photo taken on 17/3/2023 – Photo source : Wikimedia Commons

The first site was (1) Plaza Rakyat which is located on Jalan Pudu. When the project was first announced in 1993, it was to be a large-scale mixed use development in prime CBD location. Following the 1997 Asian financial crisis, the developer faced financial difficulties and the project was halted. In 2014, DBKL took over possession of Plaza Rakyat and in the following year, it was sold to a new developer. However, there has been little progress in the project until today. With the completion of commercial developments within the city like Tun Razak Exchange (TRX) and Menara Merdeka 118, Plaza Rakyat will have a huge task to market its office and commercial space, and that again, if the project ever sees the light of day.

Prior, the site was a football ground for the Selangor Chinese Recreation Club (SCRC). The club had produced many Chinese footballers who went on to don state and the black and yellow national jerseys. The most illustrious player was the late Wong Choon Wah. He was the first Malaysian player to play professional football in Hong Kong, from 1972 to 1974 and was a member of the national team that played in the 1972 Munich Olympic (the only time that we played in the Olympic). In all, he won 88 caps and scored 20 goals for the country.

UTC KL (Pudu Sentral / Puduraya Terminal) / Photo source : Eric Lim

Sitting next to Plaza Rakyat is what is known today as the (2) Urban Transformation Centre KL (UTC KL). It is one of the initiatives undertaken by the government in providing the urban community with key government and private sector services under one roof. The building was originally built to be a bus terminal / interchange and was known at that time as Puduraya Terminal (Hentian Puduraya in Malay). It was officially opened in 1976 by the late Prime Minister Tun Hussein Onn, the third Prime Minister of Malaysia. It soon became the major transportation hub in the city and as a result, it created massive congestion in the area. Bus operators were then gradually moved to inter-regional hubs in other parts of the city, namely Jalan Duta bus terminal (or Hentian Duta) and Bandar Tasik Selatan Integrated Transport Terminal (BTS ITT) which started operation on 1 January 2011. In 2011, Puduraya was renamed as Pudu Sentral after it had undergone major renovations and upgrading works. The following year, it became the Urban Transformation Centre for Kuala Lumpur.

According to Teo Chee Keong, a researcher, architect and co-author of the book “The Disappearing Kuala Lumpur”,the site of the current UTC KL was once a dam. He backed this up with a photo of the dam which he believes to be taken in the 1910’s and an old map showing a stream that flowed from Bukit Bintang (near Jalan Alor) to the dam, and continued westward towards the Central Market area and finally merged into the Klang River. Later, the British built a railway track and a road next to the dam (right and left respectively). The road eventually turned into an arterial thoroughfare connecting Jalan Pudu to Cheras. Further checking on the progress of the dam over the years, there are two historical records from Malaysia National Archives (see link below). The first document is a Minutes of Meeting dated 9/4/1903 which recorded the call for tenders for the Pudoh (the initial name) Dam Fish Farm. This confirmed the fishing activity that can be seen in the photograph taken from the book. And the second record is a document dated 17/7/1914 on the reclamation of Pudoh Dam which by this time, was downsized to a pond and accordingly called Pudoh Pond.

Photo of the dam taken from the book “The Disappearing Kuala Lumpur” – Photo source : There once was a dam in KL | The Star

Kota Raya and Wisma Fui Chiu (building on the far left) / Photo source : Eric Lim

We walked across the busy Jalan Pudu intersection towards Jalan Tun Tan Cheng Lock and stopped in front of (3) Kota Raya. Tun Tan Cheng Lock was the first President of Malayan Chinese Association (MCA). It was said that the building was built in the 1960’s but this information could not be true as the first shopping complex built in the country was Ampang Park Shopping Complex which was built in 1973 (sadly, Ampang Park ceased operations on 31 December 2017). Boosted by its high street location, Kota Raya soon became a popular shopping complex when it was opened. Overtime and with the emergence of newer and bigger shopping malls particularly around neighboring Bukit Bintang, it saw a major shift in clientele and it faded into oblivion. Today, the retail podium and kiosks in Kota Raya are mainly operated by foreigners and the fifth floor has been repurposed and converted into a budget hotel. Kota Raya has acquired a reputation as the hub for workers and tourists from the Philippines and is tagged as “Little Manila’.

Jalan Tun Tan Cheng Lock was previously known as Foch Avenue. There were two landmarks along this road, and the first was the (4) Fui Chiu Association Building. The original building was four-storey high and was built in the 1930’s. One of the tenants during its early days was the Communist Party of Malaya (or Malayan Communist Party / MCP). The party stayed on until it was declared illegal in 1948. It also houses the Tsun Jin High School when its campus was destroyed by the Japanese during the war. In November 1985, the building was torn down for the construction of a new (4) Wisma Fui Chiu. The project was delayed and only received the Certificate of Fitness in 1992. The top two floors are being used by the clan association until today.

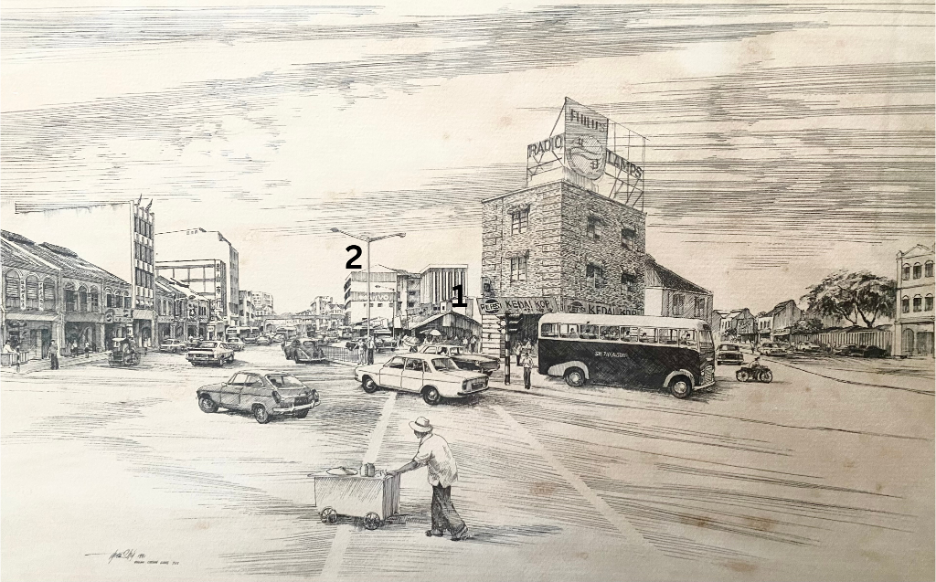

Drawing of Foch Avenue in the 1970’s, showing the exact location of Kota Raya before it was built (1) which was then a bazaar with a row of stalls and next to it on the background was Fui Chiu Association Building (2) / Photo source : Eric Lim

The second landmark was the (5) Sultan Street Railway Station. It was the second station built in Kuala Lumpur, after the first Kuala Lumpur station which was nicknamed Resident Station. The line connecting the first KL Main Station to Pudu through Sultan Street Railway Station was opened on 1 June 1893, and was followed by the extension to Sungai Besi in 1895 and Kajang in 1897. The beginning track between the first KL Main Station and Sultan Street Railway Station ran across the Klang River and between two busy carriageways located at Foch Avenue. This railway track was dismantled in the 1910’s and Sultan Street Railway Station became a terminus station. It remained until 1972 when it was closed for the construction of Puduraya Terminal. Some part of the old route is still being used by LRT Ampang Line

Sultan Street Railway Station in the 1950’s. Photo source : Asian Railways

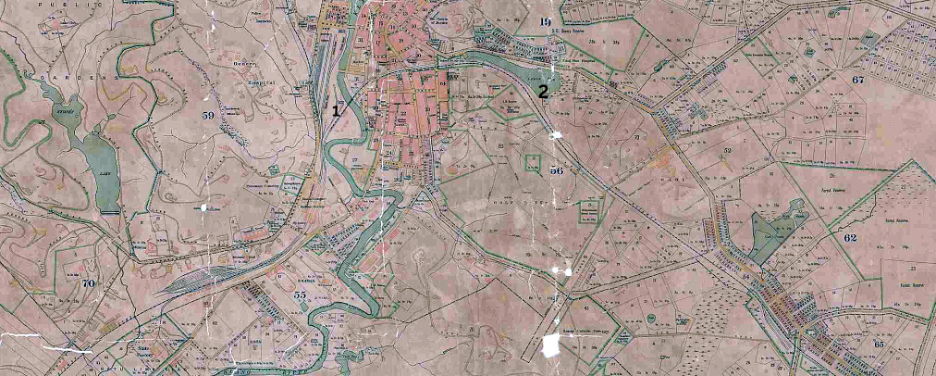

1908 KL Map showing the railway track from the first KL Main Station to Sultan Street Railway Station (1) and location of the Pudoh Dam / Pond (2) / Photo source : Asian Railways

We have reached the intersection between Jalan Tun Tan Cheng Lock and Jalan Petaling, standing directly opposite the (6) arch / gate entrance to Petaling Street. This bustling section of Petaling Street has recently been given another boost when it was voted as one of the coolest streets in the world’s best cities by global magazine, Time Out. The last few years have seen a renaissance rollicking through this part of old Kuala Lumpur with the emergence of trendy, bold and creative food, drink, and nightlife scenes. We continued our walk on the other section of Petaling Street to its end point and at the junction, it connects to High Street that runs across and a bit further down the road, Pudu Street intersects and joins Jalan Petaling, forming a triangle of sorts. And rightfully, this area was known in the early days as (7) The Triangle. However, for the Chinese, they called it ‘Ng Jee Dang’ (five lamps). This area encompasses mostly goldsmiths and pawn shops and the set up of these lamps had helped to improve visibility and security for the area. At that time, it was believed that it was the most brightly lit area in town.

(8) High Street was so named because of its elevated position above the average flood water level of the nearby Klang River and it stretches across old Kuala Lumpur.

Colourised photo of The Triangle, circa 1920’s (Petaling Street on the left, High Street on the right and Pudu Street at the center) / Photo source : KUALA LUMPUR | OLD Pictorial Thread | SkyscraperCity Forum

Today, there are many changes to the name of the areas and the streets in Kuala Lumpur. Pudu Street at The Triangle is now changed to (9) Lebuh Pudu. Still, there are a rare few that still maintain its original names and a good example is Petaling Street. Of course, today it is Jalan Petaling. But still, the Chinese, until today, prefer to call it Chee Cheong Kai / Tapioca Factory Street (茨厂街) in reference to the tapioca factory that was owned by Kapitan Yap Ah Loy and was located along the street. The Triangle / Ng Jee Dang is today known as the (7) Historic Triangle. Most of the goldsmiths and pawn shops have moved out or ceased operations, and the area is strewn with rubbish. Many homeless folks are seen in the area too. Save for some newly planted trees and shrubs that add some greenery, the Historic Triangle will never catch up to the other triangle i.e KL Golden Triangle. High Street was later changed to Jalan Bandar, and followed by another change in 1988, to be known until today as (8) Jalan Tun HS Lee. It is in honour of Colonel Tun Sir Henry Lee Hau Shik who passed away in 1988 and he was our country’s first finance minister (1957 – 1959). He was one of the representatives of the Independence Group to London which met officials from the British Colonial Office to demand independence for the Federation of Malaya.

Independence Group to London (Colonel Tun Sir Henry Lee Hau Shik, standing 3rd from right) / Photo source : MCOBs paved the way to Merdeka – Berita MCOBA

There are several historical landmarks particularly places of worship that are more than 100 years old, located along Jalan Tun HS Lee –

(10) Sin Sze Si Ya Temple(仙四师爷庙)

The temple that Kapitan Yap Ah Loy built in 1864 is believed to be the oldest Chinese temple in Kuala Lumpur. Last year, they started a museum on the top floor of the shophouses in front of the temple, that showcases the history of Kuala Lumpur and Sin Sze Si Ya Temple. The museum is open daily, from 10.00 am to 5.00 pm (effective 1 April 2024).

(11) Guan Di Temple (关帝庙)

In 1886, Chinese immigrants from two prefectures namely Guangzhou and Zhaoqing, both in Southern China, got together and formed the Kwong Siew Association. The following year, Guan Di Temple was built and is dedicated to the God of War / God of Righteousness. Besides the temple, the association also runs a Library (now called Zhou Yu Library and Information Centre after one of its founding members) which started in 1924 and a free school that provides tuition classes in Mandarin since 1927. One of the main attractions is the Guan Dao (Long Knife) which was brought in from China and is more than 100 years old. It will be on display at the centre court on certain festivals.

(12) Sri Maha Mariamman Temple

Initially used by Thamboosamy Pillai (prominent leader of the Tamil community during the pre-Independence years) and his family as a private shrine before it was moved to the current site in 1885. It transformed from attap structure to brick building in 1887 and to the current temple building in 1968. Visitors to the temple will be greeted by an impressive 5 tiered gopuram (temple gateway) which is 22.9m / 75 feet high, decorated with depictions of Hindu gods sculpted by artisans from southern India. During the annual Thaipusam festival, the silver chariot which is kept in the temple will be used to transport the statue of Lord Muruga and his consorts through the streets of KL to Batu Caves. The temple is open daily from 6.00 am to 9.00 pm.

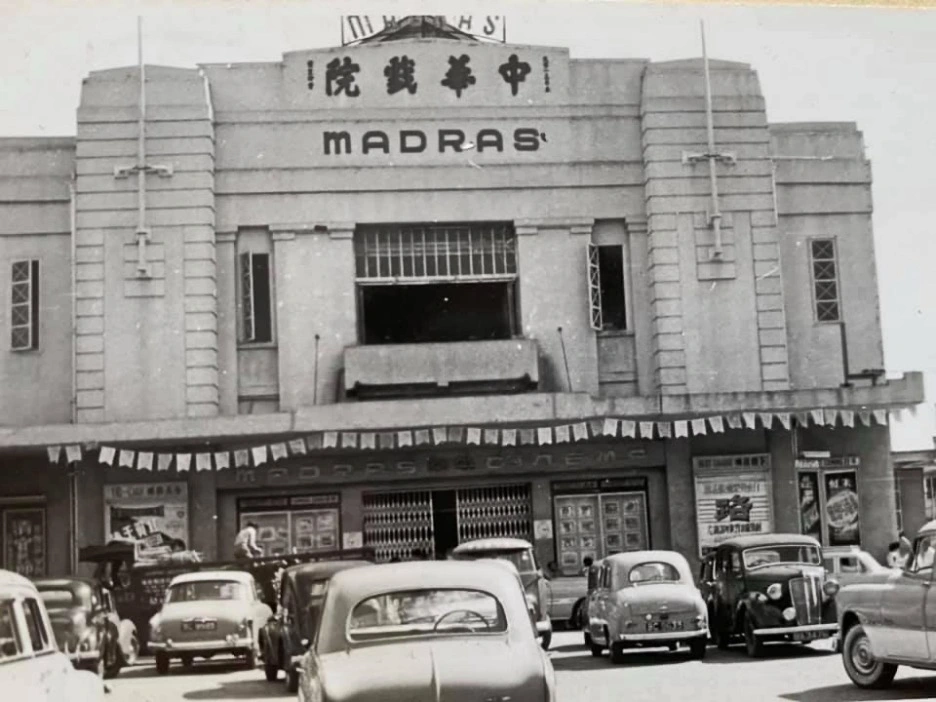

(13) Madras Theater

Opposite Sri Maha Mariamman Temple is a small alley which used to be called by the name of Madras Lane. It was called in conjunction with the Madras Theater which was sited inside. The theater shows only Chinese movies despite its name and was run by Shaw Brothers. It was burned down in a fire in 1978 but was never rebuilt and has since turned into an open air car park. And this is the new site for the relocation of the Pasar Karat / flea market which was to be carried out at the start of the year but it did not happen.

Madras Theater in the 1960’s / Photo source : KUALA LUMPUR | OLD Pictorial Thread | SkyscraperCity Forum

Moving ahead, we have arrived at another intersection where Jalan Yap Ah Loy is directly opposite where we stood. It is a short street and probably the most distinct structure located here is the (14) Maybank Tun HS Lee Branch. This corner lot, seven storey building is where Maybank first started its operations on 12 September 1960, becoming the first homegrown bank to serve Malaysian society. In its early years, Maybank was nicknamed ‘coffee shop bank’ because their branches mostly occupied shop lots that were formerly coffee shops or were situated next to one! Maybank Tun HS Lee Branch continues to operate, thus making it the oldest Maybank branch in the country. Opposite the bank and next to a red building is an alleyway called (15) Lorong Yap Ah Loy, and this is where a colourful information board depicting the life of Kapitan Yap Ah Loy is located. Lorong Yap Ah Loy was one of the laneways around the vicinity that was upgraded in a project in 2018 by DBKL and Think City (a community based organization) that aimed at creating clean, safe and vibrant spots for pedestrians and tourists. Also sited here is a pushcart lady offering cake, swiss roll and kaya puff; and farther down, a popular Chinese noodle eatery which was established before Independence.

Maybank Tun HS Lee Branch (left) and the red building (right) / Photo source : Eric Lim

We stopped for a breather on Leboh Pasar Besar, before we continued on until we reached the front of Pacific Express Hotel. Looking across the street, we have a clear view of the (16) Medan Pasar Clock Tower. And it was here at Medan Pasar that the first few wooden huts, stalls and a market were set up and it soon developed to become the commercial hub of the town. During the late 1800’s, most of the businesses were controlled by Kapitan Yap Ah Loy and the street was then known as Hokkien Street or Macao Street by the Chinese community. In 1884, Kapitan Yap Ah Loy built the first two storey brick shophouses here and some of these buildings are still standing until today. Later, under the British administration, the street name was changed to Old Market Square. The clock tower at the centre of the public square was erected in 1937 in commemoration of the coronation of King George VI but the original plaques have been removed sometime after Independence. The structure was designed by Arthur Oakley Coleman who also designed a number of buildings in Kuala Lumpur including the Odeon Cinema which was designed in 1936. Returning to the (17) Pacific Express Hotel, it was believed that it was once the location of Kapitan Yap Ah Loy’s house and Leboh Pasar Besar was then called Market Street. Leboh Pasar Besar continues past the Klang River Bridge, to the west bank of the river until it meets Jalan Raja. At the right side of the Klang River Bridge, there is a platform that offers a wonderful view of the confluence of Gombak River and Klang River (left and right respectively) with Masjid Jamek Sultan Abdul Samad (renamed in 2017) nestled in-between. In 2011, both rivers were roped in to the River of Life project which aimed at transforming its river basin areas from a previously uncompetitive and dirty river to a dynamic and habitable waterfront icon with high economic value. In the evening, the fog and lighting effects will further enhance the vicinity by transforming it into a Blue Pool. This lookout point is fast becoming a popular area for locals and tourists to gather.

2 storey brick shophouses built by Kapitan Yap Ah Loy / Photo source : KL City Gallery

Confluence of Gombak and Klang river and Masjid Jamek Sultan Abdul Samad lookout point / Photo source : Eric Lim

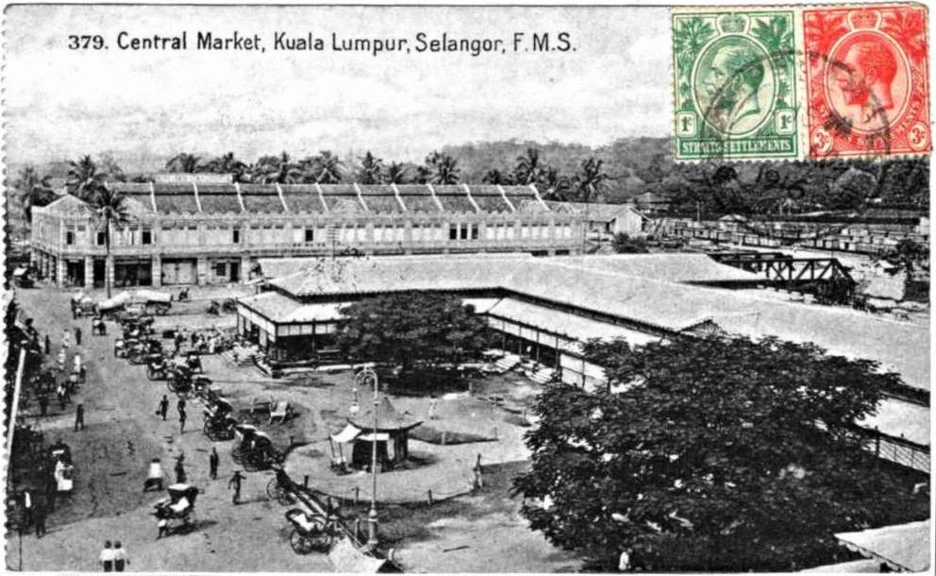

We then returned to the other side of the road to Jalan Benteng that runs along the embankment of Klang River, to our next destination, (18) Central Market or now known as Pasar Seni. The Central Market was to replace the earlier wet market that was built by Kapitan Yap Ah Loy at Medan Pasar. It was built at the same location and still functions as a wet market. It opened in 1888. Since then, it had undergone many expansions and upgrades until it was declared obsolete in 1930. The new Central Market was moved to the current site and a new building was constructed and was ready in 1937. It is built in the Art Deco architecture which was trendy during that era. The two structures mentioned earlier i.e Medan Pasar Clock Tower and Odeon Cinema are also of the Art Deco style. Art Deco comes from the French word ‘Arts decoratifs’ which literally means Decorative Arts. It was used until the 1970’s, and due to the rapid development and the massive traffic congestion in the city centre, of which the neighbouring Puduraya bus terminal which was opened in 1976 contributed much to the traffic woes, a new market was deemed necessary, thus Pasar Borong Selayang (Selayang Wholesale Market) came into being. Plan was afoot to re-develop Central Market and the surrounding area by the new owner but it was saved by concerned citizen groups including the Heritage of Malaysia Trust (Badan Warisan Malaysia), and the building was saved and declared a heritage site. In 1985, it underwent renovations and transformed to a centre for Malaysian cultures, arts and handicraft. It was officially opened by Dato Seri Rafidah Aziz who was then the Minister of Public Enterprises in 1986, in conjunction with the PATA Conference. There are new additions made to this popular tourist attraction, which include added mezzanine floors in the main building, Central Market Annexe which is located at the back of the building and Kasturi Walk; a covered pedestrian sidewalk market which took part of Jalan Kasturi (thus the name) which was formerly known as Rodger Street (named after the first British Resident of Pahang 1888-1896, Sir John Pickersgill Rodger). The Central Market / Pasar Seni is a successful example of the adaptive reuse of a historical building.

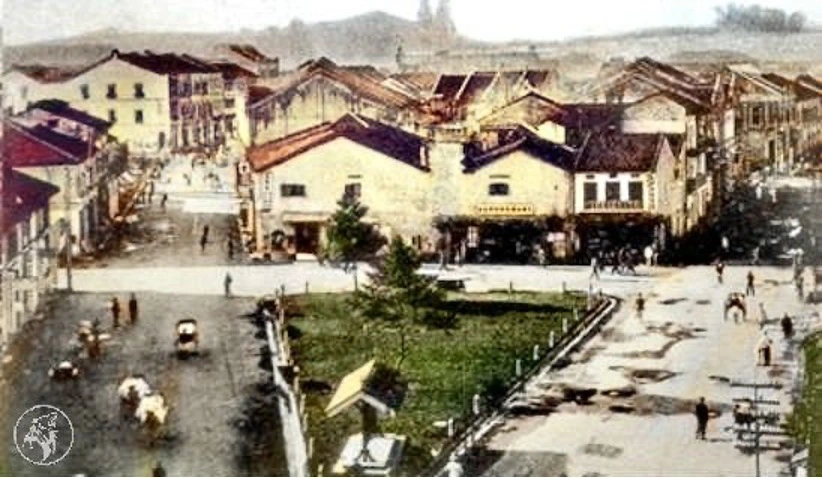

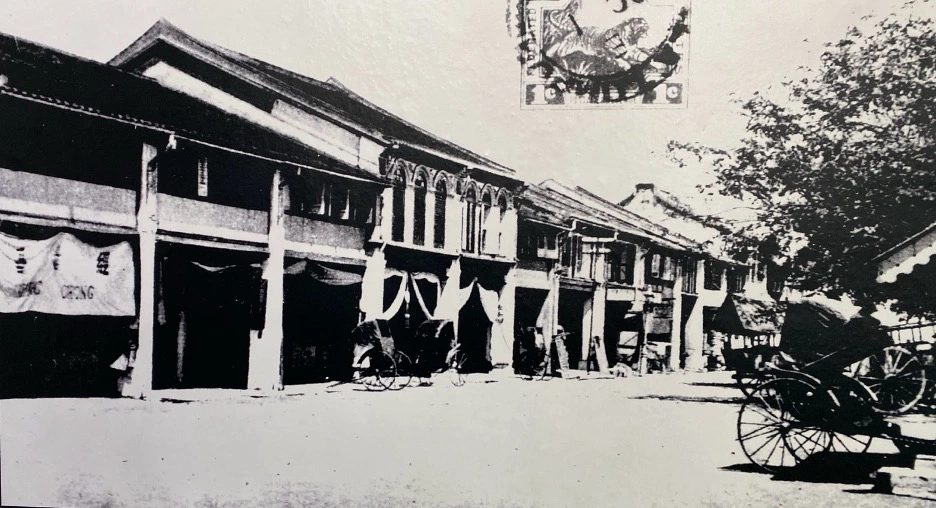

Postcard showing the first Central Market that was built in 1888 at Medan Pasar. The description from this photo source also went on to inform that the rotunda (round building with a dome on top) in the foreground is the approximate location of the Medan Pasar clock tower.

Photo source : Wikimedia Commons

Interestingly, there is an old British Colonial Post Box erected on the left side of the main entrance. According to the information available, it was placed there in 1989 and it is one of 27 such post boxes that still remain in our country. The cast iron pillar post box was made / crafted by McDowell, Steven And Company Limited, an iron foundry which was established in Glasgow, Scotland. It went on to say that the markings on the post box indicates that it was made during the reign of King George V i.e from 1910 to 1936. However the ‘GR’ insignia indicating the reign is missing. Pillar boxes were first installed on the island of Jersey, Channel Island on 23 November 1852 before it moved to the British mainland the following year. They were painted green and only changed to red in 1874 when people complained that they were difficult to find the green post boxes! By the end of the 19th century, red pillar post boxes were distributed to other Commonwealth nations.

The red pillar post box at Central Market / Photo source : Eric Lim

We are now coming to the last leg of the tour as we made our way through Jalan Tun HS Lee, passing by Guan Di Temple, Sri Maha Mariamman Temple and turning left at the MRT Pasar Seni Entrance A gate to Jalan Panggong, then to Kafei Dian for our lunch. This cafeteria is housed in an (19) old Post Office that was established in 1911. The cafeteria is conveniently located next to (20) Kwai Chai Hong which is just across the road and (21) Gurdwara Sahib Polis, located in front, on the connecting Jalan Balai Polis. And located just next to the Sikh temple is the Four Points by Sheraton Kuala Lumpur, Chinatown hotel.

Kwai Chai Hong is in the Cantonese dialect which translates to mean ‘Ghost Lane’ or ‘Little Demon Alley’, was launched in 2019 and has since been attracting visitors with its insta-worthy interactive murals,many instagrammable spots and interesting seasonal art installations. Incidentally, one can see a century old lamp post here, and it may probably be the same type as the ones installed at Ng Jee Dang!

Gurdwara Sahib Polis was originally known as Gurdwara Sahib Police High Street and it was built in 1898 by the Federated Malay States Police. At that time, more than half of the FMS Police were Sikhs. It is the second Police Gurdwara to be built in KL, the first being Gurdwara Sahib Police Jalan Parliament (previously Club Road). It was reported that there have been no major changes to the original structure of Gurdwara Sahib Polis.

Old Post Office @ Jalan Panggong / Photo source : Eric Lim

Gurdwara Sahib Polis / Photo source : Eric Lim

Now turning to the (22) southern end of Jalan Petaling which the Chinese community once referred to as Coffin Street due to the appearance of numerous funeral coffin shops along this section of the street. One of the participants remembered seeing one such shop in the 1980’s. It is the beginning point of Jalan Petaling for motorists coming in from Bulatan Merdeka. And situated at the corner, next to Lorong Petaling, is (23) Chan She Shu Yuen Clan Ancestral Hall. Looking at the facade, many would have guessed it is a Chinese temple but it is actually a clan association building. It is an association for Chinese people with the surname ‘Chan’, ‘Tan’ and ‘Chin’, all of which are written in the same Chinese characters. The association was founded in 1896 and in the following year, one of the founding members, Chan Sow Lin won a bid for seven adjoining shoplots (current location) from the Selangor Government. Construction of the building which follows the original association hall in Guangzhou, was delayed several times and was finally completed in 1906. In a recent restoration work, grey roof tiles were used in deference to the original model in Guangzhou.

Chan She Shu Yuen Clan Ancestral Hall (before and now) / Photo source : Chan She Shu Yuen Temple, Kuala Lumpurand Chan See Shu Yuen Temple Kuala Lumpur

Just a short distance away and situated on a hill to the right of Chan She Shu Yuen Clan Ancestral Hall is (24) Kuan Yin Temple. This temple was originally built by the Hokkien Chinese in the 1890’s and it served as a place to offer prayers for those buried in the graveyard that was once located on the hill. And right behind Kuan Yin Temple, is Menara Merdeka 118 which is currently the second tallest building and structure in the world, standing at a height of 678.9 m.

We made the last stop in front of the former (25) Rex Theater. It opened on 28 July 1947 and was operated by Shaw Brothers. It caught fire in 1972 and Golden Screen Cinemas (GSC) took over from 1976. Another fire destroyed the building in 2002 and it ended its glory days as a cinema. It came back to life in 2007 as a hostel but in the same year, fire again brought it down on its knees. In 2018, the building was repurposed into a cultural and creative hub known as REXKL. It also features F&B outlets, a bookstore and the newest addition of a digital art gallery on the first floor.

Rex Theater in its early days / Photo source : RXPKL

Location map

Reference

Resurrected Plaza Rakyat set to be new iconic landmark

Remembering a great footballer | The Star

There once was a dam in KL | The Star

https://ofa.arkib.gov.my/Pudoh Dam Fish Farm

https://ofa.arkib.gov.my/ Reclamation of Pudoh Pond

30 Coolest Streets in the World Right Now

Central Market – The Art Deco Structure Saved From Bulldozer

The history of letter boxes – The Postal Museum