Emna Esseghir

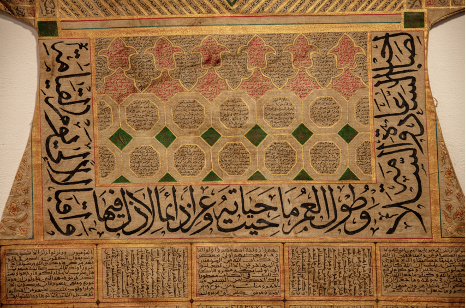

An Islamic ottoman talismanic shirt

(Source : https://www.orientalartauctions.com/object/artisla47916-an-islamic-ottoman-talismanic-shirt)

Imagine holding a garment crafted with painstaking care, where each stitch tells a story of centuries-old tradition and every pattern whispers ancient wisdom. Each talismanic shirt, adorned with symbols shrouded in mystery, acts as a tangible bridge between the earthly and celestial realms.

In the Islamic tradition, known for its emphasis on clarity and rationality, the talismanic shirt presents a contradiction – its intricate design captivates with an irresistible allure, yet it challenges the foundational principles of faith that prioritize logical inquiry and unwavering devotion. Within the intricate tapestry of this garment lies a narrative as timeless as humanity itself, a story of yearning and aspiration. It echoes our deep-seated desire for protection and our longing to connect with the unseen forces shaping our existence. This shirt embodies the eternal dance between tradition and modernity, belief and skepticism, urging us to ponder the delicate interplay of faith and reason.

Thus, the talismanic shirt transcends mere fabric, becoming a symbol of our eternal quest for meaning and connection. It serves as a tangible reminder of our innate curiosity about life’s mysteries, inviting us to delve into the depths of our spiritual consciousness. In its presence, we’re encouraged to contemplate the profound complexities of faith and spirituality, embracing the beauty found in the enigmatic unknown.

Why do humans need “protection” ?

The use of talismans is not exclusive to Islam but finds resonance across various religious and spiritual traditions, including Hinduism, Buddhism, and others. In Hinduism, for example, amulets and talismans are known as “yantras” or “lockets”, and are believed to possess divine powers that provide protection, blessings and spiritual guidance. Similarly, in Buddhism, practitioners often carry amulets known as “thokcha” or “phurba,” which are believed to offer protection against negative energies and obstacles on the spiritual path. These talismans often feature sacred symbols, mantras or images of deities, serving as reminders of spiritual principles and aiding in meditation and devotion.

Across various cultures and religious traditions, the use of talismans reflects a universal human desire for protection, guidance, and connection with the divine. Whether in the form of taweez, yantras, or amulets, these symbols serve as tangible expressions of faith and devotion, offering comfort and reassurance to believers in times of need. Moreover, the cultural and traditional significance of talismans transcends religious boundaries, with individuals from diverse backgrounds embracing these symbols as expressions of their cultural heritage and identity.

Psychologically, the act of wearing or possessing talismans can provide a sense of empowerment and agency, allowing individuals to feel more confident and secure in their daily lives. Additionally, the rituals associated with obtaining and wearing talismans can foster a sense of connection with one’s spiritual beliefs and community, promoting a deeper sense of belonging and purpose.

The appeal of talismans extends beyond religious affiliations, encompassing a wide range of cultural, spiritual and psychological needs. As symbols of faith, protection and tradition, talismans continue to play a significant role in the lives of believers worldwide; offering a source of comfort, strength and inspiration across diverse religious and cultural landscapes.

What is a talismanic shirt ?

An Islamic ottoman talismanic shirt

(Source : https://www.orientalartauctions.com/object/artisla47916-an-islamic-ottoman-talismanic-shirt)

A talismanic shirt stands as a unique fusion of garment and spiritual artifact, embodying mystical and protective properties woven into its very fabric. These shirts, found across diverse cultural and religious contexts, serve as tangible manifestations of spiritual beliefs and practices, offering wearers a tangible connection to the divine and a sense of comfort and protection in their daily lives. In Islamic culture, talismanic shirts, known as “jama’ah al-tawiz,” are meticulously crafted with symbols, inscriptions, and sacred verses from the Quran, believed to bestow blessings and safeguard the wearer from harm.

Each shirt is a testament to the unique traditions and beliefs of its creators, with intricate designs and symbols reflecting the spiritual heritage of the community. From intricate patterns to specific inscriptions, talismanic shirts serve as more than just clothing; they are conduits for spiritual connection and sources of solace and protection in a complex and ever-changing world.

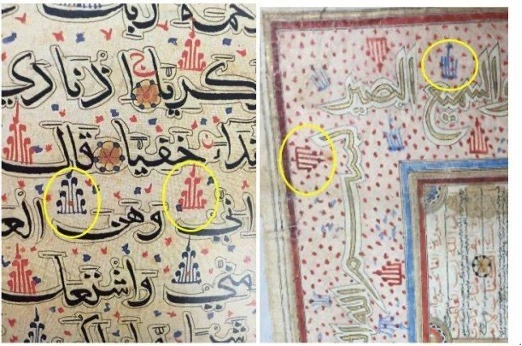

Image on the left: detail of a 15th-century Sultanate Quran, with the same motif (circled in yellow) resembling the word ‘Allah’ written in Arabic that is also present on the borders of the talismanic shirt. India, 15th century, © Khalili collection | Image on the right: detail of the talismanic shirt, India, 15th–16th century. Museum no T.59-1935 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

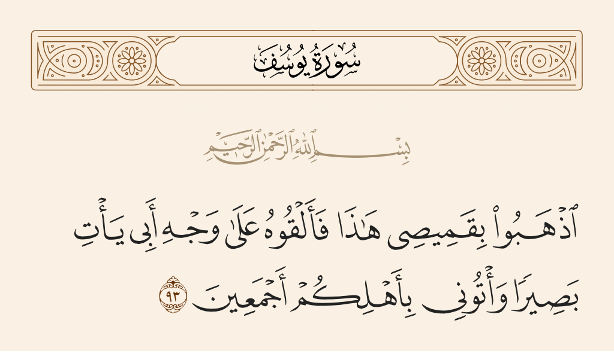

Magic Shirt in Quran

There is a story about Surah Yusuf Ayat 93 (12:93 Quran): “Go with this my shirt, and cast it over the face of my father: he will come to see (clearly). Then come ye (here) to me together with all your family.”

Here is the story of the shirt of Joseph (Yusuf), which he sent to Jacob (Yacoob) from paradise; and the secret behind Jacob regaining his sight from that hour.

The essence of the story mentioned is that when Nimrod (Namrood) threw Abraham (Ibrahim) into the fire naked, The Angel Gabriel descended to him with a shirt and a breath from paradise. He clothed him with the shirt and seated him on the breath, and the shirt remained with Abraham until he clothed Isaac, and Isaac clothed Jacob.

So Jacob took it and placed it in an iron or silver casket and hung it around Joseph’s neck when he feared for him from the evil eye.

The Angel Gabriel instructed Joseph to send it to Jacob so that his sight would be restored by the fragrance of paradise; for the fragrance of paradise will heal the sick and bring relief to those who are afflicted.

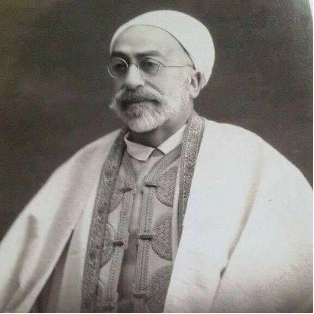

Muhammad Al-Tahir bin Ashur

(Source: Wikipedia)

The scholar Muhammad Al-Tahir bin Ashur commented on this narration in his exegesis, “Al-Tahrir wa al-Tanwir,” : It is said that the shirt was the shirt of Abraham, although the shirt of Joseph was brought by his brothers to their father when they came, with false blood on it. It seems that sending his shirt was a sign of the truthfulness of his brothers in what they conveyed to their father about the news of Joseph and his safety… As for Jacob regaining his sight through the shirt, it was a grace from Allah.

The spiritual and artistic sides of Islamic talismanic shirt

Example #1:

Talismanic Shirt 15th–early 16th century

(Source : https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/453498)

This talismanic shirt is decorated with painted squares, medallions, and lappet-shaped sections. Its surface features intricate designs encompassing most probably the entire Quran inscribed within. Surrounding these areas are the ninety-nine names of God, written in gold against an orange background. On the reverse side, a central panel bears a proclamation in gold script declaring, “God is the Merciful, the Compassionate”

Example #2

An Islamic ottoman talismanic shirt

(Source : https://www.orientalartauctions.com/object/artisla47916-an-islamic-ottoman-talismanic-shirt)

This shirt is decorated with intricate writing in Naskh script, in lots of bright colors and designs like cypress trees. The writings are from the Quran, prayers to God, and other sacred texts. They come in different sizes and shapes, sometimes mirrored or on different backgrounds in colors like black, red, green, and gold. On the back, there are more writings about Allah and parts of the Quran, surrounded by fancy designs like gilt lotus flowers and leaves, making the shirt look both fancy and spiritual.

Example #3:

An ottoman talismanic shirt, 18th century

(Source : https://www.orientalartauctions.com/object/art3002406-an-ottoman-talismanic-shirt-18th-century)

A striking shirt embellished with a rich tapestry of text, woven in Naskh, Thuluth and Kufic scripts, and adorned in an array of vibrant hues. It also has a myriad of panels, circular motifs, and intricate cypress tree designs, all meticulously arranged across the fabric. The inscriptions, drawn from the Quran, feature invocations, divine attributes, prayers, and the names of Allah, alongside verses rendered in a captivating blend of sizes, shapes, and colors. There are striking patterns and mirrored forms set against a backdrop of black, red, blue, and gold. The back of the garment features a captivating display of Allah’s names, Quranic verses and talismanic numbers, encircled by opulent gilt lotus blossoms, flowers, and foliage, completing a masterpiece of artistry and spirituality

Example #4

Talismanic shirt – Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts

Source: [https://islamicart.museumwnf.org/database_item.php?id=object;isl;tr;mus01;18;en&cp]

The front of the shirt has a round collar and is open down to the level of the abdomen. The entire surface of the shirt is decorated with Quranic verses, prayers, magic formulas and numerological charms. The back part of the shirt features a design of naturalistic flowers decorated in coloured pigments.

The inscriptions on talismanic shirts consist mostly of chapters and verses of the Quran. In addition to these, the names and epithets of God (the Asma al-Husna), the names of various prophets and the four major angels, the seal of the Prophet Muhammad and poems praising him. Occasionally written on the shirt is the hilya (Description of the Prophet), and the names of Fatima, her sons Hasan and Husayn, the first four caliphs, as well as the signs of the zodiac.

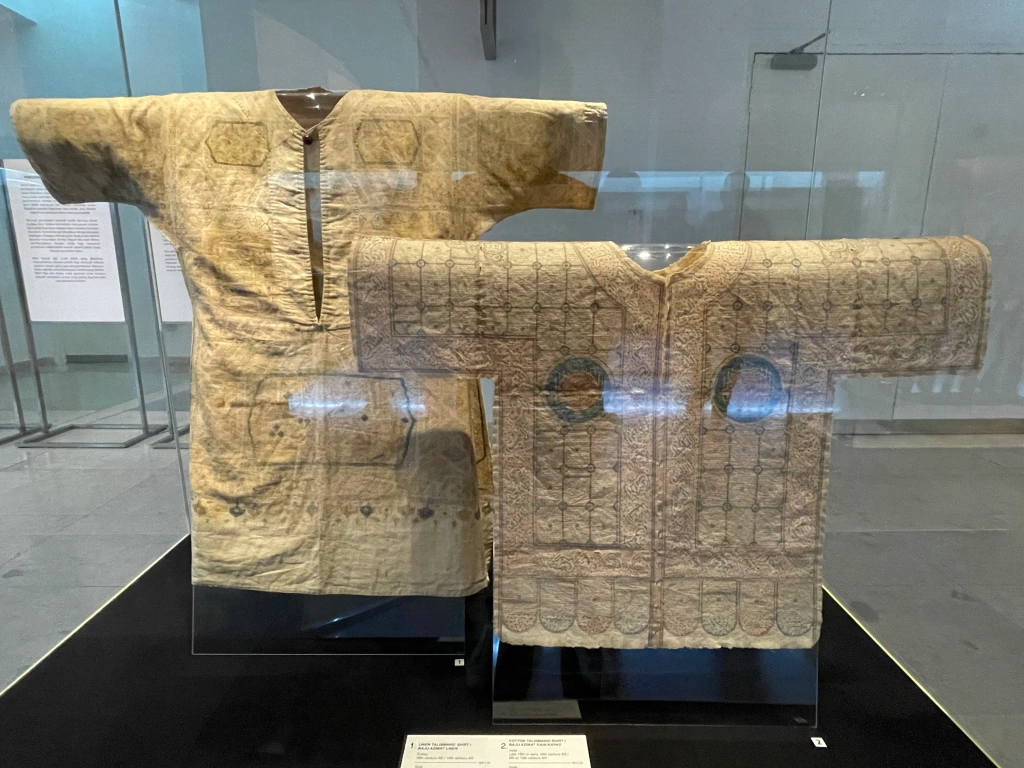

These are few examples of Islamic talismanic shirts; you can see two models exhibited in the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia.

Talismanic shirt from the Islamic Art Museum

credit : Emna Esseghir

In conclusion, the Islamic talismanic shirt represents more than just a piece of clothing; it is a profound symbol of spiritual belief and protection, deeply ingrained in Islamic culture. Adorned with intricate inscriptions, sacred verses, and symbols, these shirts serve as tangible manifestations of faith; offering wearers a sense of connection to the divine and a source of comfort and protection in their daily lives. Across diverse cultural and religious landscapes, talismanic shirts stand as testaments to the enduring power of belief and tradition, bridging the gap between the material and the spiritual realms. Through their intricate designs and spiritual significance, these shirts continue to captivate and inspire, reminding us of the profound depths of spirituality and the human quest for meaning and connection.

References

https://www.orientalartauctions.com/object/art3002406-an-ottoman-talismanic-shirt-18th-century

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/453498

https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/fabric-of-india/guest-post-a-warriors-magic-shirt

https://ajammc.com/2021/04/30/premodern-ppe-talismanic-shirts/

https://islamicart.museumwnf.org/database_item.php?id=object;isl;tr;mus01;18;en&cp]