To be read in conjunction with A Self-Guided Cultural Tour of Muzium Negara

Introduction

Welcome to Muzium Negara. This tour will take us through a journey with snippets of Malaysian history. We shall trace prehistoric times through to Malay kingdoms and the colonial era to the rise of a modern nation.

Murals and Lobby

Murals

The sweep of Malaysia’s culture and history is emblazoned across the facade of the National Museum in the form of two massive murals flanking the main entrance made of glass mosaics from Italy. The artist, Datuk Cheong Lai Tong, created the murals in 1962 after winning a competition commissioned by Tunku Abdul Rahman, Malaysia’s first Prime Minister. The two murals are titled Episodes of Malayan History (the East Mural) and Malayan Crafts and Craftsmen (the West Mural). You’ll notice that they are labelled Malayan as Malaysia only came into being just after the completion of the museum.

East Mural: Episodes of Malayan History

The East Mural, dealing with history, spans the years from the 12th century of the early Hindu-Buddhist Malay Kingdom to 1957, which marked the Independence of Malaya. Moving forward in time from the right, we see the date 1409 which marks the arrival of Admiral Cheng Ho from China with three figures presenting gifts to the Sultan of Melaka who had already embraced Islam. In return, tributes were presented showing gratitude for China’s protection. Melaka developed into an amazingly successful entrepôt, where 84 different languages were spoken.

The year 1475 marks an epic keris battle in which the Malay hero, Laksamana Hang Tuah vanquished his friend Laksamana Hang Jebat on the orders of the Sultan. Attracted by the profitable spice trade, Portugal attacked and defeated Melaka in 1511, controlling the thriving port until the Dutch conquered it in 1641. The Dutch remained in charge until 1824. Melaka’s last Sultan’s son founded the Johor dynasty. Around 1720, the Bugis re-established the Bendahara Dynasty in Johor.

In 1840 the Kedah Sultanate was restored after having been invaded and subdued two decades earlier by the Siamese. The figures paddling the boat are sending a bunga mas, a tree made of gold, to the Siamese king as tribute. Meanwhile the British involvement in tin had grown and it was called in to help settle a dispute that broke out between two groups of rival Chinese secret society tin miners in Perak.

The resulting Pangkor Treaty in 1874, established peace between the two factions allowing the tin trade to flourish. It also settled a simultaneous ascension conflict among two Perak Malay rulers, recognizing Raja Abdullah as the rightful Sultan of Perak. As a result of the Treaty, the British for the first time actually took on an administrative role in terms of governing, which had previously been in the hands of the Sultans.

In 1886 the first Selangor government railway was constructed opening up further investment opportunities. By 1900 rubber plantations were established. Rubber together with tin eventually became the major commodities of this land until the 1980s. World War II was in progress by 1941, and Japan, desirous of materials like rubber and tin to develop their economy, attacked the colony and became the occupying power for the next four years. Following the War, the desire for freedom arose and the new nation, Malaya, was granted independence by Britain in 1957.

Lobby

The museum’s soaring open lobby greets visitors as they enter through the main doorway. Windows, some displaying cut out wooden panels, extend vertically on the two opposite walls at the front and back of the museum, allowing light to flood in.

Close examination of the long wooden beam at the very pitch of the ceiling that extends from the front of the hall to the back reveals intricately carved decoration. These adornments continue on the portions of the shorter beams radiating out from the walls towards the centre beam.

A majestic staircase dominates the back wall splitting into two, both sides leading to the upper galleries. Exquisite blue and white geometric patterned tiles cover the floor. These were donated to the museum by the Government of Pakistan in 1963 when it opened and are still impressive to this day, 60 years later.

“No glass, no boxes,” was the remit for the museum design, issued by Tan Sri Mubin Sheppard, the first director of the National Museum from 1958 to 1963, manager of the project. He believed as a Malaysian museum, it must be something local. And so the design created by architect Ho Kok Hoe was adopted from the 1735 Balai Besar or Great Hall, an audience hall for the Sultan of Kedah in Alor Star. Muzium Negara was the only government building at that time, designed for the new nation after Merdeka reflecting traditional Malay architecture, which we can experience in the lobby.

Gallery A

Welcome to Gallery A. In this gallery we will discover a journey of humankind from hunter gatherers to early settlements, the types of tools used for everyday life and some of their beliefs and practices.

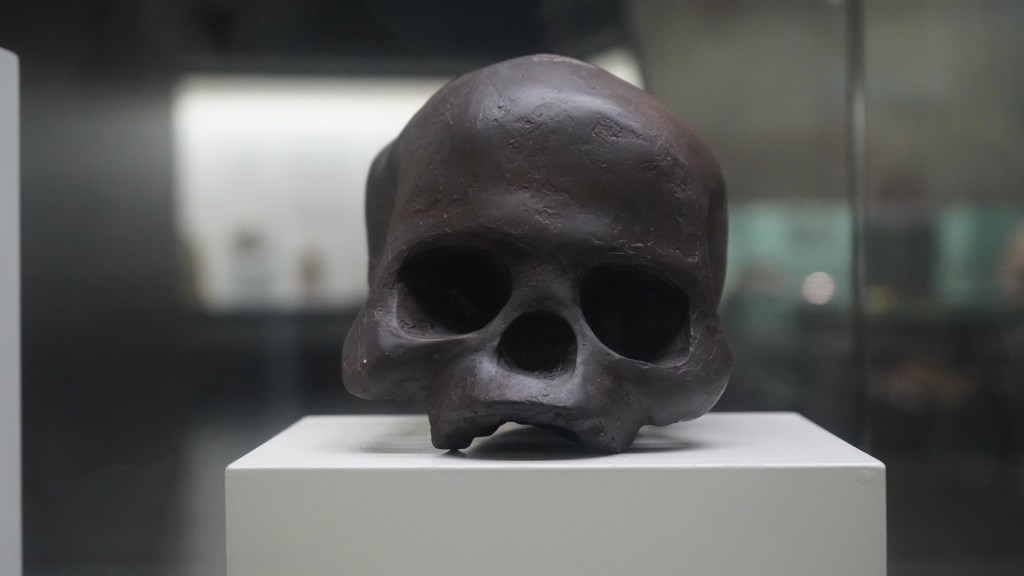

Deep Skull

The Deep Skull is a fossilized human skull discovered in Niah Cave, Sarawak, Malaysia in 1958. It is believed to be the skull of an anatomically modern human who lived in Southeast Asia around 35,000 to 45,000 years ago. The Deep Skull is so named because it was found in a deeper layer of sediment compared to other human remains found in the cave.

The skull is characterized by its elongated shape, sloping forehead, and robust features. It is believed to be of a young adult female, as indicated by the size and shape of the cranial features. The Deep Skull is of particular interest to anthropologists and archaeologists as it provides valuable insights into the physical characteristics and evolutionary history of early humans in Southeast Asia.

One of the most interesting aspects debated about the Deep Skull is that it may show evidence of having been modified through a practice known as “cranial deformation.” This is a cultural practice in which the skull is intentionally reshaped during infancy or childhood by applying pressure to the head using a variety of methods, such as binding the head with cloth or boards. The reasons for this practice are not entirely clear, but it may have been done for aesthetic or social reasons.

The Deep Skull of Niah remains an important artefact in the study of human evolution and serves as a testament to the diversity of human populations throughout history.

Evolution of Tools from the Paleolithic to the Neolithic Age

The evolution of tools from the Paleolithic to the Neolithic Age was characterized by the gradual development of human ingenuity and innovation. In the Paleolithic Age, early humans used simple stone tools such as choppers, scrapers, and hand axes for hunting, butchering, and food processing.

One important stone tool site found is at Kota Tampan in Perak, where a stone tool workshop was found intact as it had been abandoned about 74,000 years ago due to a volcanic eruption in Sumatra.

As time went on, humans created more complex tools such as spears, bows and arrows, and fishing nets. In the Neolithic Age, humans began to settle in one place and engage in agriculture and animal domestication. This led to the development of polished stone tools and the use of metals, such as copper, bronze, and iron. The evolution of tools during this time period reflects the changing needs and challenges faced by early humans as they adapted to their environment and advanced in technology and civilization.

Kodiang Tripod Vessel

Many debris of pottery were discovered at the site of Gua Berhala in Kodiang, District of Kubang, Kedah. These pottery objects were studied and elaborated on the technical aspects of the cones manufacture, noting, for instance, the way the cones were formed and decorated, as well as the firing conditions. Finding new fragments helped to propose that the cones belonged to a type of tripod vessel.

Archeologists think that the perforations in the legs may at first sight seem inexplicable and out of place. They may have been intended originally to permit the escape of air from the hollow interior during firing. Similar tripod vessels were discovered in other parts of Southeast Asia, including Thailand.

Perak Man

Perak Man refers to the prehistoric human remains that were discovered in 1991 in the Lenggong Valley, Perak, Malaysia. The skeletal remains, estimated to be around 11,000 years old, consist of a fragmented skull, jawbone, teeth, and a few bones from the spine, arms, legs, and hands. He represents a Stone Age human and one of the most complete Palaeolithic human skeletons discovered in South East Asia.

The body was placed in a one-metre-deep shallow grave in an East West Orientation, and perpendicular to the cave entrance.

Despite his handicap (congenital deformity known as Brachymesophalangia Type 2A where his left arm and hand was much smaller than his right arm and hand), he lived to be between 40 to 45 years old, a good age range for his time. It is speculated that Perak Man must have been a reputable member of his tribe and a high-up member in the society judging by his elaborate ceremonial burial. The discovery of Perak Man remains an important contribution to the understanding of human evolution and migration patterns in Southeast Asia.

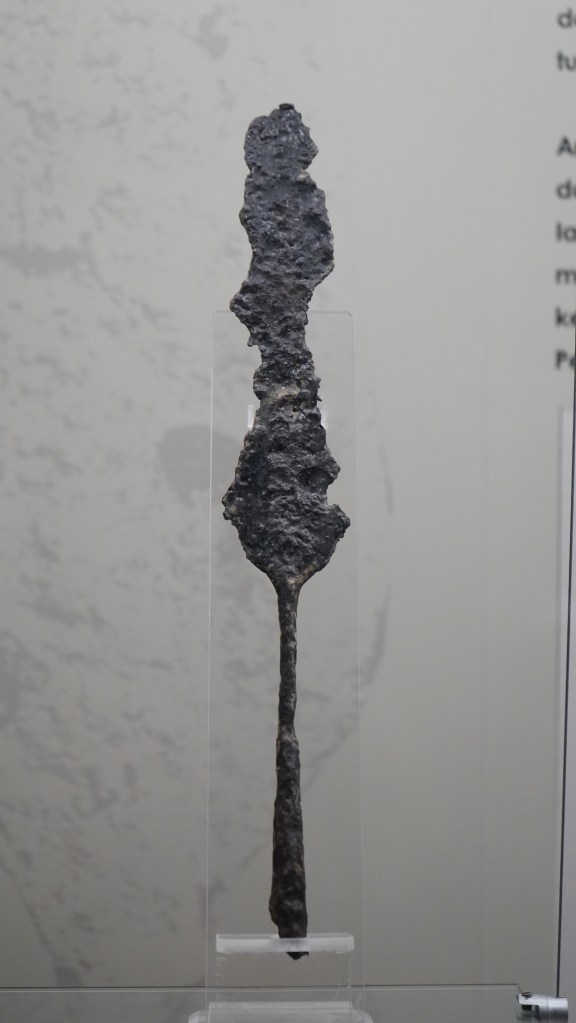

Tulang Mawas

Tulang Mawas is a long shafted socketed iron axe. It has a unique shape resembling the rib bones of animals and was only found in the peninsula.

Tulang Mawas literally “ape’s bones” found its origins in the legendary Tulang Mawas, the ancient hairy ape man with iron hands who once lived in the forest. It can be a folk memory but some scholars think that this legend could be a reference to an ethnic group in forests observed using this tool.

The use of iron was cheaper and more hard wearing than Bronze and easier to extract. In fact iron was the most abundant metal, suitable for simple smelting and was widely distributed in the form of surface deposits that could be scraped up without elaborate mining procedures.

Tulang Mawas may be found in the states of Perak, Pahang and also Selangor. The types of tools found in hordes are the long-shafted axes, sickles, knives and spearheads and it is speculated that these were part of a tool-kit

Many are wondering if these were tools or weapons. This is still debated because all tools are nowadays disfigured by rust and many found have deteriorated but the basic shape is identifiable. Most likely, tulang mawas had multi functions and since iron items were costly, the possession of iron tools was restricted to those who are higher in the hierarchy.

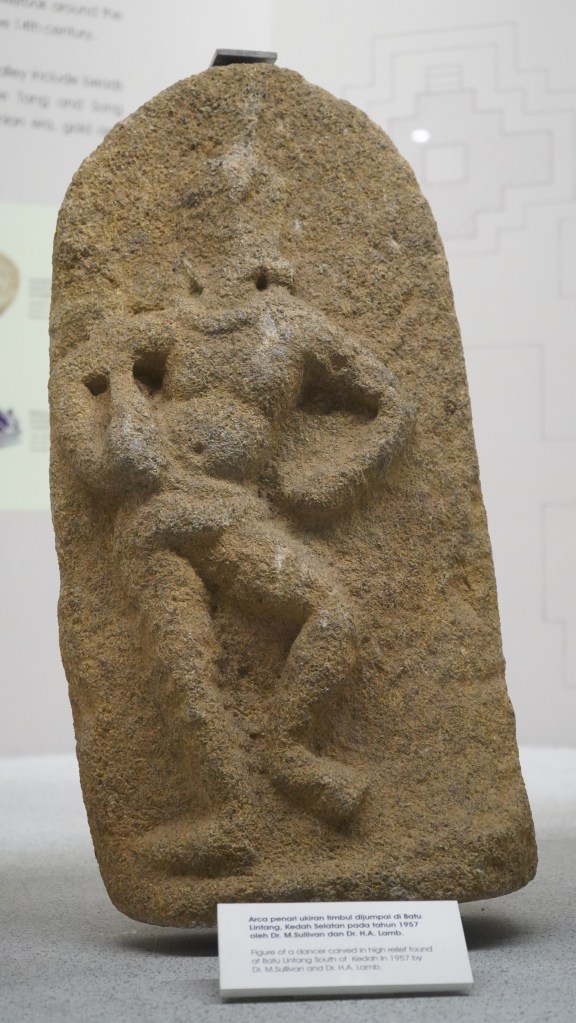

Stone sculptures in Bujang Valley

Bujang Valley, located in the northern state of Kedah in Malaysia, was an important center of trade and cultural exchange in Southeast Asia. During that Era, both Hinduism and Buddhism coexisted in the region, and their respective influences can be seen in the various archaeological and historical artefacts found in Bujang Valley.

Many candis, which are the remnants of temples, show evidence of a blending of Hindu and Buddhist imagery and statues became the medium through which a deity channelled its cosmic energy

One object showing the Hindu influence is the stone tablet with a Hindu dancing figure (Dvarapala) sculpted in relief which was discovered at Batu Lintang in south Kedah in 1957. Portrayed as fearsome, a Dvarapala is a term from Hindu and Buddhist cultures that refers to a type of deity or guardian figure often depicted as a statue or carving placed at the entrance of a temple or sacred space.

The Buddhist influence is seen in the Seated Bodhisattva, carved in terracotta. This artefact was unearthed at Pengkalan Bujang. It is a popular subject in Buddhist art representing the ideal of the Buddhist path, which is the attainment of enlightenment and the liberation from suffering. By meditating in the posture of a seated Bodhisattva, one can cultivate the same qualities of serenity, compassion, and wisdom.

Gallery B

The Malay Kingdoms gallery offers an overview of the kingdoms and sultanates established within what is known as the Malay Archipelago, aka the Malay World, between the 2nd and 16th centuries. This terminology refers to maritime Southeast-Asia whose peoples share cultural characteristics, history, and heritage. Technically, it covers a vast region as far-reaching as Madagascar to the Easter Islands, though what forms the emphasis of this gallery are areas that constitute modern day Malaysia – the Malay Peninsula and Borneo.

Remnants of Age-Old Malay Kingdoms in the Malay Peninsula

Archaeological evidence shows that Malay kingdoms had already been in existence since the 2nd century in locations like Borneo, Sumatra, Java, the Celebes and Moluccas as well as in parts of Indochina. The Kingdom of Kedah Tua, or Kataha, also Chieh-Cha, for example, dates back as early as the 5th century, possibly earlier. Historical artefacts found in the Bujang Valley in Kedah reveal that it was a significant node for trade. Among such artefacts is a 7th century makara shown here in the gallery. The makara – a composite mythical creature in the form of part elephant and part fish, was discovered in Kampung Sungai Mas.

Likewise, foundation stone bases for pillars have also been found in the Bujang Valley. They’re believed to be parts of Hindu-Buddhist temple structures which used to dot the area. Collectively, these artefacts communicate a Hindu-Buddhist culture that was present in Kedah Tua. Furthermore, historical records also tell us that other kingdoms like Gangga Negara in Perak, Foloan in Terengganu, Chih Tu in Kelantan and Temasik in Singapore once existed in the Malay Peninsula.

A Hindu-Buddhist Past

Indic culture was prevalent throughout classical Southeast-Asia. With the introduction of Hinduism and Buddhism, Sanskrit, and Indian-style political system, combined with existing indigenous traditions and beliefs, a hybrid Hindu-Buddhist culture unique to the region was born. Evidence of this syncretism can be found in Malaysia through the discovery of religious and/or artistic artefacts.

The Avalokitesvara or Bodhisattva of Compassion bronze (typically existing in the Buddhist pantheon) exhibited here before you is a strong proof of this Hindu-Buddhist hybridity. A bodhisattva is an enlightened being who has delayed achieving nirvana in order to help others attain enlightenment. This bronze is believed to be from the Gangga Negara era, an early Buddhist kingdom in the 8th – 9th century which collapsed after succumbing to attacks from the Chola Empire in the 11th century. Intriguingly, this statue is rather unique as it possesses attributes that are associated with Shiva, the Hindu deity of destruction. These attributes include: a high jatamakhota crown, a kendi jar, and a tiger skin slung around the waist. Discovered in Bidor, Perak, the image weighs 63kg and stands at 93cm tall.

Similarly, the Jalong Brahmin or Buddha Brahmin bronze cast in the Srivijayan style exhibited adjacent to the Avalokitesvara is the Vedic sage Agastya. He is highly revered and celebrated for his role in the spread of Hinduism, and for having compiled the Agattiyam – the earliest book on Tamil grammar, as well as for founding the Silambam – a form of martial arts.

The Founding of Melaka

The kingdom, and later sultanate, of Melaka traces its early history to circa 1400 when a settlement was formed by Parameswara, a Palembang prince. At that time, his priorities would have primarily been security and survival as he had killed the ruler of Temasek, a vassal state of the Siamese. This instigated their revenge. Melaka was the perfect location for his hideout. Parameswara was clever to seize the opportunity presented by collaborating with the sea gypsies and coastal communities who had already inhabited the area to develop the settlement as a port-of-call. As time went by, Melaka gradually gained footing and eventually became a superpower to be reckoned with. Threats from the Siamese and Majapahit powers were reduced as Parameswara pledged his loyalty to China for support and protection. In return, envoys and tributes were sent to China regularly to pay homage to the emperor. The conditions were optimal for Melaka to thrive as a commercial hub. One of key factors was the strict enforcement of the Undang-Undang Laut Melaka (Melaka Maritime Laws) which laid down the legal foundations on which trade was conducted. Likewise, the Undang-Undang Melaka (Melaka Laws) – the first law digest in the Malay world, set the standards of governance of the port town that offered confidence and certainty to its diverse inhabitants.

Ceramics from Shipwrecks

The seabed is a silent and wondrous resting place for shipwrecks of times past. Their discovery offers us an insight into the extent of the trade routes (aka maritime highways) established regionally that witnessed the participation of various communities as early as the 10th century. Off the coast of Malaysia alone, there are over 14 documented shipwrecks recovered. Here in the gallery, we are able to see some of the items recovered from the Turiang shipwreck (dated circa 1370), Longquan shipwreck (dated circa 1400) and Xuande shipwreck (dated circa 1540). The items recovered were varied. For example, the Turiang carried large Chinese celadon guans and dishes made in the renowned Longquan kilns in Zhejiang, China. The Longquan shipwreck on the other hand carried celadon dishes, vases and cups etc. which are exhibited here too. Also in the vitrine are items from the Xuande shipwreck where blue-and-white ceramics, and a variety of Thai ware were found. On closer inspection, these artefacts give us invaluable glimpses of the wares that were in trend of respective time periods – their origins, influences, materials and styles. On a larger perspective, chronicling the production and consumption patterns of peoples across geographies enabled by trade.

The Arrival of Islam in Melaka

One crucial turning point in the history of Melaka is the conversion of its second ruler Sultan Megat Iskandar Shah to Islam which further bolstered its position in the region as a distinctive economic superpower. By the middle of the 15th century, Melaka had largely been Islamised. The diorama before you depicts an artist’s impression of the conversion ceremony. The conditions formed by a Muslim monarch made it attractive for Muslim merchants on top of an already flourishing economy. Melaka subsequently became a centre for Islamic thought and intellectualism, which attracted many Islamic scholars. Expectedly, this setting had a strong and lasting impact on the local arts and society.

The Hybrid Society of Melaka

Melaka’s reputation as an international port was a key contributing factor to its cosmopolitanism. It witnessed the coming together of various peoples of different backgrounds from across the Malay archipelago and beyond, namely Siam, Burma, China, India, Persia, Arabia, etc. There were those who came only for trade, and there were those who chose to settle and intermingle with the locals, birthing new communities. No less than 84 languages were spoken in the port city during its peak, with Malay being the lingua franca. The Baba Nyonyas, Chitty Melaka, and Kristang communities in Melaka, descendants of Chinese traders, Indian traders and Portuguese settlers from the 15th and 16th century respectively, whom we refer to as the Peranakans, were formed under these circumstances. The cultural construct of these communities seamlessly bound the existing Malay cultural elements with those of respective backgrounds to create something colloquial yet unique. Their illustrious cultural heritage is well-preserved up to this day, and some of the arts and cultural items used by these communities are displayed here in this gallery: ceramics, jewellery, and traditional wear.

Gallery C

Introduction

Melaka was enjoying a golden era due to its strategic location at the Straits of Melaka. An effective administration, its close relations with China, monopolising the spice trade coupled with the coming of Islam, it became an important, prosperous and thriving entrepot.

Due to this too, Melaka became a target and attracted foreign powers and the fall of Melaka to the Portuguese in 1511 signalled the beginning of the colonial era in Malaya. This era of more than 440 years impacted many changes in the political, social and economic development in Malaya.

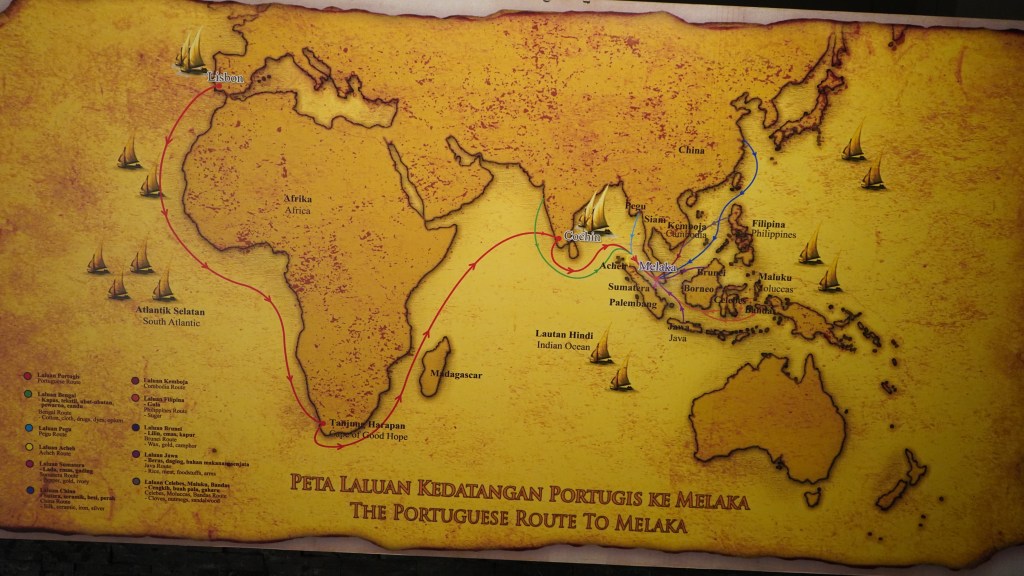

The Portuguese

The fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453, made the Asian land route for spices more costly and challenging. The Treaty of Tordesillas signed in 1494 between Portugal and Spain, saw Portugal seek alternative maritime voyages and colonies to their east, where Melaka is situated. This fitted in well to their intentions to expand their empire and conquer Melaka, well-known for its riches.

The King of Portugal sent a delegation to Melaka led by Diego Lopez de Sequeira to foster ties to trade especially in spices as it is was a lucrative business. However, they were not welcomed due to their misconduct with the locals and also, the dangers the Portuguese represented, especially the way they dealt with the Muslims in India. Ultimately, the King of Portugal sent 18 ships and 1,000 men led by Alfonso de Albuquerque to attack and capture Melaka in 1511 and ruled for 130 years. The Portuguese exploration and colonisation policy driven by the objectives of Glory, Gold and Gospel was not only to trade but to control the trade, the people and their lands. The Captain of the Fort administered Melaka and managed public affairs, financial and religious matters. For the local population, it retained the Bendahara, Temenggong and the Shahbandar to assist the Captain of the Fort.

In the defeat, the ruling family of Melaka fled to Pahang and eventually established a new Malay kingdom in Johor and Riau.

The Dutch Rule

The Dutch East India Company or the Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC), was a company-state that maintained armies, signed treaties with local rulers and governed vast possessions with its trading centre in Batavia (now Jakarta). The VOC captured Melaka for military and economic ambitions to control the maritime route, the lucrative spice trade and also to prevent other powers from taking Melaka and competing against the Dutch, The Dutch launched numerous attacks and finally in 1641, with the assistance of the Johor Sultanate and other allies, the Dutch captured Melaka and ruled for 183 years. The Governor was the authority that headed the Dutch administration in Melaka.

The British Occupation

The British came to establish a foothold in the Malay Peninsular to be part of the East-West trade between India and China which included new fashionable and highly profitable commodities like tea and opium from China. British involvement in Malaya began with the establishment of trading posts by the British East India Company in the late 18th century. Francis Light in 1791 and Stamford Raffles in 1819, negotiated with the Sultan of Kedah and the Johore chiefs, respectively, to gain control of Penang and Singapore. In 1824 the Anglo-Dutch Treaty was signed with the British occupying Melaka and surrendering Bencoolen in Sumatra to the Dutch. All these three states were combined administratively in 1826 and became known as the Straits Settlement and hence the start of the British influence in Peninsular Malaya.

The Pangkor Treaty

The British, to maintain stability and free-flowing trade out of Singapore and Penang, began their involvement in local politics with the signing of the Pangkor Treaty in 1874. Succession dispute in the royal family and conflict between Chinese secret societies that controlled the tin mines paved the way, for the British to organize and direct the governments of the Malay sultanates to protect their commercial investments.

The Pangkor Treaty was signed between Raja Abdullah of Perak and Sir Andrew Clarke in 1874, acknowledging Raja Abdullah as the legitimate Sultan of Perak and that he accepted a British Resident to be in charge of all State affairs except those concerning Islam and Malay customs. JWW Birch became the first British Resident of Malaya. This model was followed by the states of Selangor, Pahang and Negeri Sembilan that formed the Federated Malay States.

Impact of British Intervention to Commodities

British involvement in the administration of the Malay States saw major improvements and progress. The growing importance of commodities like the tin and rubber industry to the economy encouraged the government to build better road and rail systems, infrastructure, communication, education and a government system.

Tin mining is the oldest industry in Malaya and has been around since the time of the Melaka Sultanate. The importance of tin grew with the expansion of the food canning industry and the use of tinned food in Europe and America during the nineteenth century. Chinese immigrants were brought in to work in the tin mines. With the increase in demand, tin-mining improved from the ‘lampan’ mining to the open-cast “lombong”, and eventually the methods improved up to the introduction of the tin dredge by European companies. From the 20th century, Malaya became a major producer of tin.

Meanwhile, the rubber industry began in Malaya in 1878 when the first rubber tree was planted in Kuala Kangsar. Henry Ridley introduced rubber as a cash crop and Malaya became a major producer of natural rubber and to meet the shortfall of labour, the British brought in Indian migrants to work in the plantations.

The Japanese Occupation

As Japan entered World War Two, their increasing demand for tin, rubber and agricultural resources naturally caused Japan to include Malaya and Singapore as countries to be colonised. Since Britain was focusing on the war on the European front, Japan took the opportunity to invade British Malaya in December 1941. Interestingly, their onslaught included the mere bicycle that they brought and also obtained from local residents and retailers. The relatively quiet bicycles provided high mobility through the plantations and jungles, giving them a huge advantage in surprising the enemy. On 8th December 1941, Japanese troops landed in Kota Bahru and it took them 68 days to complete their invasion with Singapore and shortly after, Borneo. After the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, Japan surrendered.

Gallery D

In this gallery, we are exploring local history from the end of World War II right up to present time. The Japanese invasion of Malaya in 1941 discredited the British ability to protect the local people. This contributed to the rise of Malay nationalism and the hunger for independence became an aspiration. The return of the British to post-war Malaya posed new challenges leading up to independence.

From Nationalism to a Nation

The British Malaya economy through commodities like rubber and tin, expanded significantly under colonial rule. The size and role of government expanded as well. This brought about a need for a modern educational system as there was a need for trained people of local origin to work. Due to this, the British government introduced secular English education.

The Pondok or hut school was commonly found in rural areas. Education was informal where priority was given to religious education. Early Malay nationalism was inspired by a group of Pan-Islamic activists who received their education in the Middle East. Malay journalists and educators were thus exposed to ideas for independence there. Together with the secular intellectuals, the religious scholars took to influence the masses through their writings.

The turning point for Malay nationalism was the inauguration of the Malayan Union in April 1946. All citizens were given equal rights and with the loss of sovereignty by the Malay rulers, the British faced strong opposition to the Malayan Union so much so that it was replaced by the Federation of Malaya in 1948. Citizenship rules became stricter and rulers’ sovereignty were restored under the federation.

The Road to Independence and Beyond

The Federation of Malaya that was created under British protectorate ultimately manifested in the displeasure of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) which had fought alongside the British during the war. The Communists therefore started armed agitation in June 1948 resulting in the British declaration of Emergency in Malaya which lasted until 1960. During the emergency, movement of goods and people were restricted so as to isolate and contain the Communists who used guerilla tactics. The Communists claimed that they were fighting to free Malaya from the British yoke. Independence was seen by the larger community as the answer to stop the Communists. The British had stressed that independence would not be granted without evidence of unity among the races in Malaya.

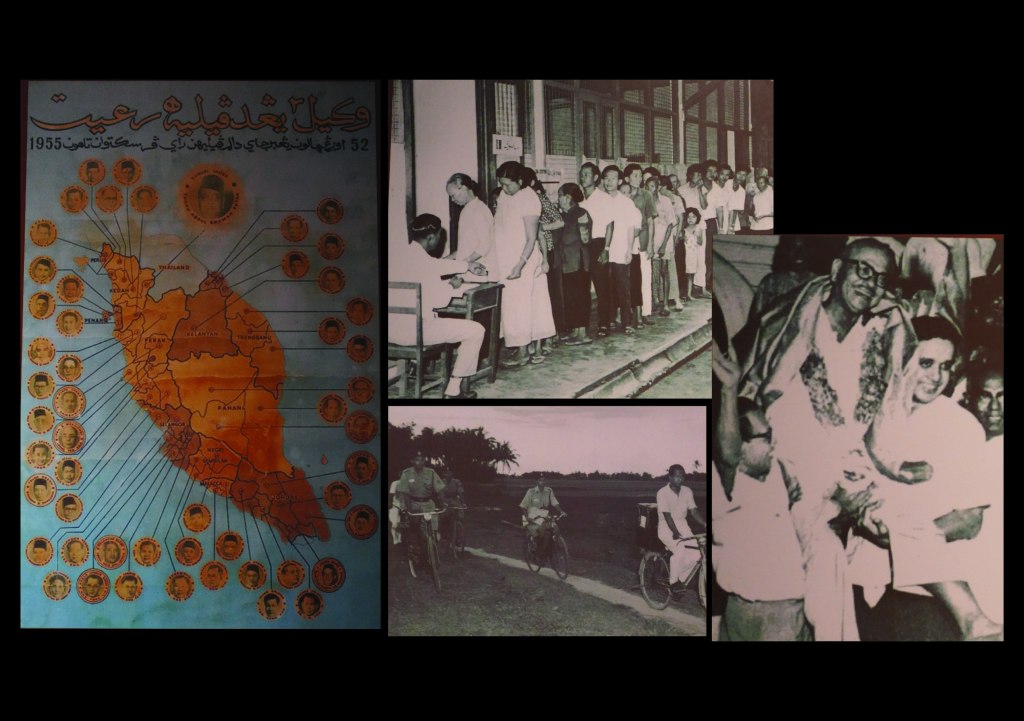

In 1955, the Alliance Party consisting of United Malay National Organisation (UMNO), Malayan Chinese Association (MCA) and Malayan Indian Congress (MIC) had a landslide victory in the first Federal Elections. The Alliance Party swept 51 of the 52 seats, proving that the main races could work together and that independence would not result in an outbreak of civil war, as feared. With this victory, the independence of Malaya was easily negotiated and agreed for August 1957. UMNO’s leader Tunku Abdul Rahman became the first Prime Minister of the independent Federation of Malaya.

Merdeka or Independence was the repeated shout of Tunku Abdul Rahman, broadcasted throughout Stadium Merdeka on 31 August 1957. The cry of independence was quickly echoed enthusiastically by more than 20,000 people of Malaya who were present to witness this monumental event. This day marks the end of the 446 years of foreign domination of the Malay Peninsula since the invasion of Portuguese in 1511.

On 27 May 1961, Tunku Abdul Rahman had mooted the merger of the remaining British colonies which include Singapore, North Borneo or Sabah, Sarawak and Brunei to become Malaysia. The Cobbold Commission report shows that eighty percent of the Sarawak and North Borneo population had supported this formation. Brunei had opted to withdraw. On 16 September 1963, Malaysia was formed. Even though Malaysia was formed by consensus of those concerned, it faced opposition in its early years. Indonesia had a policy of confrontation against Malaysia until 1966. The Philippines staked their claim on Sabah and only re-established diplomatic relations with Malaysia in 1964. Singapore became an independent nation after its separation from Malaysia on 9 August 1965. Malaysia today is made up of 13 states and the Federal territories.

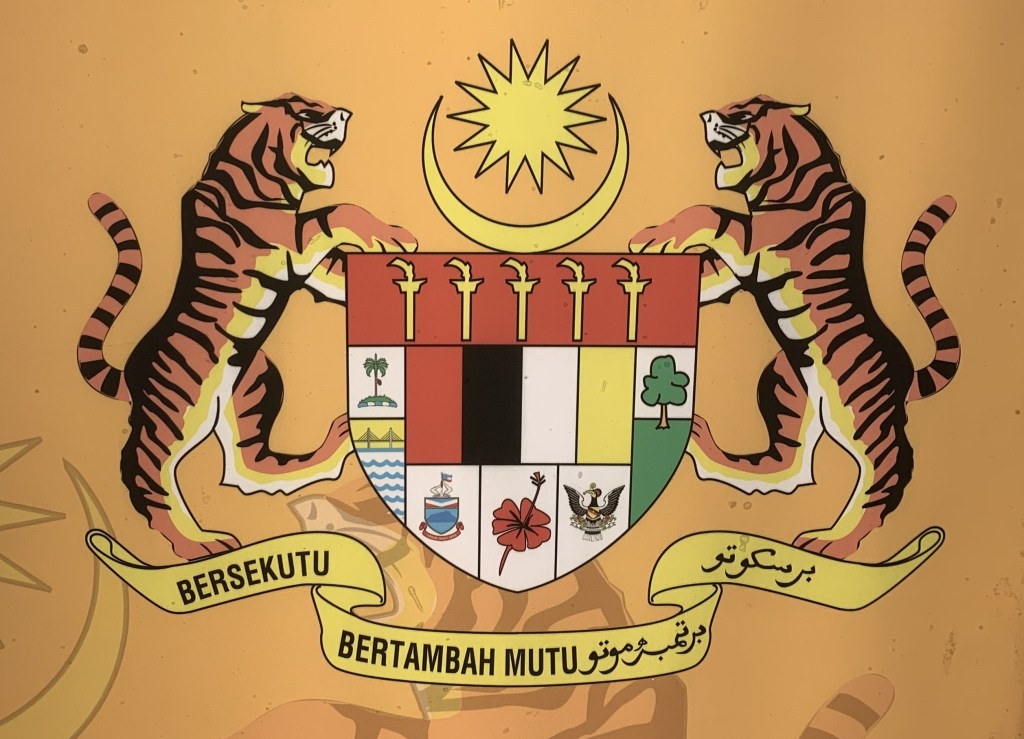

National Symbols of a New Nation

Malaysia, a new nation, has its own national identities. These include our monarchy, our national anthem, flag, the coat of arms and our national flower. These identities represent the strength, courage and unity of the Malaysian people to live in harmony in the pursuit of progress.

Royal Headdress (Tengkolok Diraja)

The traditional Malay headdress or Tengkolok is made of cloth, which can be tied in many shapes and styles. The royal headdress is a very important part of ceremonial dress for the Malay Royalty which is worn by the Sultans and the Yang Di-Pertuan Agong, the Supreme Ruler of Malaysia. The Yang Di-Pertuan Agong is elected among the nine royal rulers every five years. The royal headdress is folded and tied in the style originating from Negeri Sembilan as Malaya’s first Yang Di-Pertuan Agong, Tuanku Abdul Rahman was from this state.

National Anthem – Negaraku

The origin of this anthem was a song, “Rosalie”, a French creole song from the Seychelles. This was very much loved by Raja Abdullah, the Sultan of Perak who was then in exile on the island. It became a popular tune named “Terang Bulan” as well as the Perak State anthem. The national anthem plays an important role in developing patriotism whilst emphasising the ambitions, aspirations and hopes of Malaysian people.

Flag of Malaysia – Stripes of Glory

The Flag is a symbol of leadership, honour, dignity and sovereignty of a country. The flag in Malay culture is normally associated with the status of the Royal Rulers. On the evening of 31 August 1997, Tun Dr. Mahathir bin Mohamad, who was Prime Minister then, had carved another historical moment when he announced a new name for the Malaysian flag, JALUR GEMILANG or Stripes of Glory.

A total of 14 equal red and white stripes marks the 13 states and a Federal Territory. The crescent symbolises Islam as the official religion while the Royal colour yellow is indicated on both crescent and star. The 14-pointed star again represents a nation of 13 states and federal territories.

The National Crest – Jata Negara

Jata Negara or The Coat of Arms of Malaysia is the Malayan symbol that was agreed by the Rulers of Malaya on 30 May 1952. It comprises five elements: a shield (as an escutcheon), two tigers (as supports), a yellow crescent and a yellow 14-pointed star (as crest) and a banner (as motto). As the Malaysia emblem evolved from the coat of arms of the Federated Malay States (FMS) during the British Colonial rule, the current crest resembles European heraldic designs and symbolically includes all states.

National Flower – Red Hibiscus

The Bunga Raya or the hibiscus is the national flower of Malaysia. It was declared as the national flower by the first Prime Minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman in 1960. The flower represents the courage and vitality of the people.

Many People, One Heart

Malaysia is a unique nation where colours, flavours, sounds and sights come together as one. A country with people of various ethnic groups, have been able to live in peace and harmony since its independence in 1957. Each year Malaysians celebrate festivals of Hari Raya Aidilfitri at the end of Ramadan, Chinese New Year, Deepavali, the festival of lights, Tadau Kaamatan (Harvest Festival) by Kadazan Dusun in Sabah and Hari Gawai (Thanksgiving and Harvest Festival) by Gawai Dayak in Sarawak. Underneath such diverse cultures, festivals, traditions and customs, lies the same spirit – the spirit of being Malaysian.

Conclusion

Exploring history is like having a conversation with the past. It is empirical, multilayered, and often invokes imagination. We hope you have enjoyed snippets of Malaysian history from prehistoric times through Malay kingdoms and the colonial era to the rise of a modern nation, Malaysia as it is today.

Note

This self-guided tour material is brought to you by the Museum Volunteers, Department of Museums Malaysia. For more information on the free guided tours at Muzium Negara and on what we do, kindly visit https://museumvolunteersjmm.com/mv-tours-at-muzium-negara/.