By Chuah Siew Yen

Situated in north west Borneo, on the banks of the Sarawak River at approximately the same latitude of Kuala Lumpur, across the South China Sea, is Kuching.

Kuching was trading town for at least two centuries under the Bruneian Sultanate. In 1841, it became the capital of the Brooke ‘Rajah-dom’ after the territory west of the Sarawak River was ceded to James Brooke. From then on, Kuching became Sarawak’s capital, receiving attention and development, which continued under the second Rajah, Charles Brooke. After the third Rajah, Charles Vyner Brooke ceded Sarawak as part of the British Crown Colony in 1946, Kuching remained its capital … and retained its status as state capital after the formation of Malaysia in 1963.

Granted city status in 1988, the City of Kuching is administered by two separate local authorities – Kuching North (administered by a Commissioner) and Kuching South (administered by a Mayor). Kuching experienced further development and was declared ‘City of Unity’ for its racial harmony, on 29 July 2015 by One Malaysia Foundation.

This capital city is the main gateway for travellers visiting Sarawak and Borneo, and a member of the UNESCO Creative Cities Network (Field of Gastronomy).

Aerial view of Kuching City. To the left is north Kuching with the State Legislative Building dominating, and south Kuching to the right. Source: YouTube, Gazetica Explorer

Being driven around the city on a recent visit, I observed its natural and built heritage. As I mingled and chatted with its people and enjoyed the cuisine, I can attest to the fact that Kuching is indeed a city of unity as well as a city of gastronomy and creativity.

The diversity that we see in Kuching touches all spheres of life, from the people and nature to culture and food. This is the place where traditions thrive and history remains in the time-worn streets of Old Kuching where stories of the White Rajahs are retained. Kuching holds on to its past as it moves into the present. Juxtaposed among the new are Brooke era buildings in neo-classical and baroque designs which peer out in between modern contemporary structures. At every turn in the city, one is greeted with a mosque, temple, church or colonial building.

Sitting majestically on the north bank of the Sarawak River is the State Legislative Building with its distinctive umbrella-inspired roof, also reminiscent of the Bidayuh longhouse and the Melanau hat. Here, Sarawak’s 82 elected representatives (assemblymen and women) debate and pass laws.

In the courtyard of Fort Margherita with award-winning guide, Edward Mansel, who took us on a walking tour ‘On the Trail of the White Rajahs’. Photo by author.

The Astana was built in 1870 by Charles Brooke. It was the venue for various meetings of the General Council from 1873 – 1937. Laid out in the style of an English manor house, it was the third and last residence built by the Brooke Rajahs. Photo source: Old Kuching Smart Heritage booklet.

Walking along the waterfront, the Darul Hana Bridge catches the eye with its two towers designed to complement the hornbill-like structure of this 2017 icon. This S-shaped bridge, 12 meters above the water, is the only pedestrian crossing linking north and south Kuching.

The bot penambang (water taxi) still makes the crossing as it is the fastest and probably the cheapest way to cross the river, especially for the villagers of Kampung Boyan, Kampung Gersik and surrounds.

On the opposite bank of the river, moving away from the promenade, are the historical and heritage buildings that give Kuching its unique character such as Sarawak’s former administrative centre found in the Old Courthouse built in 1874, and the hub of the earliest trading activities. The area is a meeting spot of old and newer mosques, Brooke-era buildings, Chinese temples, and shop houses along India Street, a covered pedestrian street lined with shops and stalls selling textiles and sundries. The city then was a self-segregated area where heterogeneous communities of Chinese, Indian, and Malays lived and thrived in different areas while peacefully co-existing with each other.

Midway is a narrow alley named Masjid India Lane that passes by the entrance of the India Mosque and leads to Jalan Gambier, where Kuching’s Indian spice traders and Chinese hardware merchants are found. Further up is Carpenter Street, named for the many woodwork shops set up in the last century.

When James Brooke landed in 1839, the row of shops along the river were made of wood and nipah. This Attap Street soon became the prime trading area due to its proximity to the original piers, where goods were unloaded at the jetties and wharfs. Business activities picked up, and in 1872, the second Rajah had some shops rebuilt with bricks, with a 5-foot walkway in front connecting the shops of each block.

A street of Kuching town shortly after the surrender of Japan, image taken on 12 Sept 1945. Shops with 5-foot walkway visible. Photo source: Australian War Memorial

In 1884, a fire ravaged the wooden buildings, but these were quickly rebuilt with bricks. They are the quaint old shops we see today in Main Bazaar Road facing the river—a vestige of Kuching’s past, a lower working-class neighbourhood with hardware and bicycle shops amid gambling and opium dens, and brothels—and a haven for clandestine activities. What is interesting is that the local people were not aware of the Japanese spies in their midst who disappeared two days before the Japanese landing on 8 December 1941.

Here is the historic core of the city, well-preserved as a peaceful merging of Indians, Chinese, and Malays in its modern-day co-existence, an eclectic mix of history, culture, tradition, and community. A walk through the layers of history and architecture and everything in between is both educational and relaxing.

Main Entrance, Sarawak Club. The Club was established in 1876 for the recreational and entertainment needs of the White Rajahs and government officers. Sarawak-valued belian timber was used for the roofing truss and shingles. Photo by author.

As Kuching prospered, its boundaries expanded with de-centralisation combined with development of new commercial centres. Hotels, shopping malls, tertiary education institutions, civic and religious structures, and infrastructure were constructed or upgraded to meet the needs of an evolving demographic trend towards urbanisation and modernity. As in the past, Sarawak’s built environment was largely concentrated in Kuching, it being the capital and government centre.

After the opening of the Tun Abdul Rahman Yacob Bridge in 1974, the development of the city shifted from the old town to the northern side of the Sarawak River. Many government offices relocated here and Petra Jaya is now the administrative centre for the Sarawak Government.

The State Library of Sarawak is set amid beautiful surroundings and overlooks a man-made lake. The library offers a direct-to-consumer book borrowing service. Also in Petra Jaya, are the Sarawak Stadium, a multi-purpose sports facility with 40,000 seats, and the Sarawak State Jamek Mosque.

State Library of Sarawak (Pustaka Negeri Sarawak) in Petra Jaya Photo source: Wikimedia Commons

Greater Kuching is a metro area of 2,030 km sq., almost the size of Greater Kuala Lumpur at 2,243km sq., but with a much smaller population.

Sarawak’s population is made up of about 26 major ethnic groups, with sub-groups within them. The two biggest groups are the Ibans and the Bidayuhs. Those groups in the interior are collectively referred to as Orang Ulu (people of the interior). Inter-racial marriages, formerly rare and only between closely related groups, are increasingly common in this day and age.

The culture of some of these indigenous communities has been influenced by Islamic practices, while others have converted to Christianity. However, indigenous beliefs, customary rites, and social customs known as adat continue to be practised. Those practices, entwined with traditional beliefs, are carried out through customary law or adat.

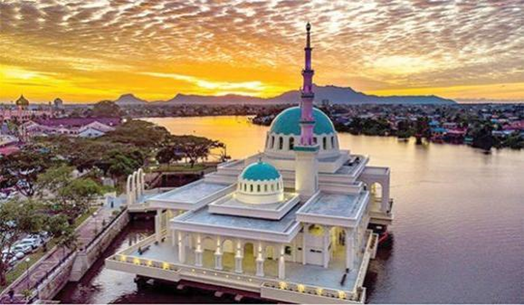

The Floating Mosque sits on the banks of the Sarawak River. It can accommodate 1,600 worshipers. At dusk, the architecture is accentuated when it is flooded with the light of the golden sunset. Photo source: KuchingSarawak.com – (https://www.kuchingsarawak.com/2020/01/10/top-3-beautiful-masjids-of-kuching/)

The diversity of Sarawak’s (and Kuching’s) population is seen in the places of worship throughout the city. The Floating Mosque is at least one of eight religious places in the historical core of Kuching. Masjid Bandaraya Kuching replaced the old wooden mosque in 1968. Masjid India, built in 1879, is the oldest extant in the city. Masjid Bandaraya Kuching is the main mosque in Kuching. It had served as the state mosque before the new mosque was built in Petra Jaya.

Other places of worship are St. Thomas Anglican Cathedral, originally built in 1856, followed by the neo-Gothic-style St. Joseph Cathedral, built in 1894 but has since been replaced by a modern building in 1969.

St Thomas Cathedral Kuching. Photo source: CW Food Travel (cwfoodtravel.blogspot.com/2010/01/kuching-architecture-st-thomas.html)

St. Peter’s Catholic Church is undergoing construction, which, when completed, will resemble Westminster Abbey in miniature. The Gothic-style building will have pointed spires, ogival arches, flying buttresses, rose windows, and a bell tower.

Temples in the vicinity are the Tua Pek Kong Temple, the Taoist Hong San Si Temple built in 1848, the rebuilt Siew San Teng Temple, and the 1889 Hiang Tiang Siang Ti Temple, an Indian temple and a Sikh gurdwara.

The original Sarawak Museum. Photo source: Wikipedia Commons

An aerial shot of the Borneo Cultures Museum at Jalan Tun Abang Haji Openg in Kuching. Photo source: Bernama

Museums – big or small, special or unique – are found all over Kuching. Among them are the original Sarawak Museum built in 1891 by Rajah Charles Brooke. Chinese History Museum housed in the former Chinese Courthouse built in 1912 by Rajah Vyner Brooke and the Sarawak Islamic Museum housed in the 1930 Maderasah Melayu Building also built by Rajah Vyner. But the Borneo Cultures Museum (BCM) tops it all. Opened in March 2022, this 5-storey building with distinctive architectural features reflecting the traditional crafts of Sarawak, displays the best examples of Sarawak’s material culture.

With Dr. Louise Macul, centre, founding member, Friends of Sarawak Museum in the BCM bookshop. Photo by author.

Murals in the Sarawak State Museum, commissioned by Tom Harrisson, Curator of the Sarawak Museum (1947 – 1966). Photo by author.

Kenyah painted wood carving by Tusau Padan, in Hotel Telang Usan. Photo by author.

The Kenyah-owned Hotel Telang Usan exhibits paintings by Kenyah artist extraordinaire Tusau Padan (1933–1996). Tusau often said he was doing ‘all that the old people taught me, not to seek fame but to preserve a beautiful tradition’. The paintings here complement the four masterpieces by artists from Long Nawang, East Kalimantan, in the old Sarawak Museum.

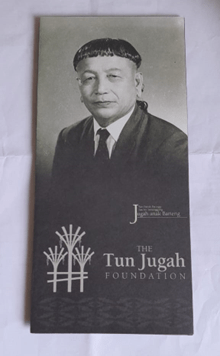

The Tun Jugah Foundation, registered in 1985 perpetuates the memory of Tun Datuk Patinggi Tan Sri Temenggong Jugah anak Barieng by collecting, recording and preserving Iban culture, language and oral history. The museum/gallery promotes traditional methods of Iban weaving through a display of costumes and pua kumbu, antique and modern, complete with weaving materials and implements. There is also an exquisite collection of beads, silverware and jewellery.

Janet Rata Noel, Curator, Museum and Gallery, Tun Jugah Foundation, at her loom. The Foundation encourages all its staff to learn the Iban crafts of weaving and beading. The Foundation conducts demonstrations and workshops. Photo by author.

Born in a longhouse in Kapit, Jugah anak Barieng was a Malaysian politician of Iban descent. Even though he had no formal education, he played a fundamental role in the formation of Malaysia in 1963. Tun Jugah is said to be ‘the bridge to Malaysia’ for without his signature (thumbprint!) there would not be any Malaysia. Photo source: Tun Jugah Foundation.

Kuching is also a major food destination. Each ethnic group has its own delicacies with varying preparation methods. Examples of ethnic foods are the Iban tuak (rice wine), Melanau tebaloi (sago palm crackers) and umai (raw fish in lime juice) and Orang Ulu urum girua (pudding).

A bowl of Sarawak laksa. Photo source: Goody Foodies (https://goodyfoodies.blogspot.com/2014/04/recipe-sarawak-laksa.html)

Wild herb: Motherwort. Photo source: Wikipedia.

Some of the notable dishes, such as Sarawak laksa, kolo mee, and ayam pansuh, have made their way into the menus of Kuala Lumpur eateries, their tastes being increasingly appreciated by the palates of west Malaysians. Creeping in are midin (edible fern), gula apong-flavoured desserts, kway chap (broad rice noodles in spiced broth with offal), and salted ikan terubok (a local fish).

Still relatively unknown are ayam kacangma, a chicken dish made with motherwort, its unique bitter taste complemented with tuak and a popular post-natal dish; wild brinjal (terung Dayak/terung assam) soup made with smoked or salted fish with ginger, garlic, onion, and pepper; and de-shelled smoked-dry prawns, chewy and flavourful, in kerabu or salads. Fresh prawns are shelled, then straightened (unlike the ordinary salted, curled up dried prawns) before being laid on mesh trays to be smoked. It’s a laborious process and retails at RM250 a kilo.

Terung Dayak, a native cultivar of wild eggplant. This local eggplant is spherical in shape and comes in yellow to orange hues. It is called terung asam due to its natural tart flavour. Photo source: Borneodictionary.com

Bario rice is a rare grain grown in the Kelabit Highlands, where the soil is fertile and the temperature is cool. It is irrigated by unpolluted water from the mountains and it takes six months for the grain to mature, yielding aromatic, marble-white rice with a sweet taste and slightly sticky texture, richer in minerals than normal rice. Cultivated by hand with no pesticides using traditional farming methods and with only one yield a year, real Bario rice is rare and retails at RM25 a kilo.

There is a cheaper, lesser-quality grain that goes by the same name, and many Malaysians are not aware of the difference. Genuine Bario Rice has been registered as a product of Geological Indication (GI), the practice of labelling food based on national or place origins to protect it as part of a nation’s heritage. Bario salt from the salt springs is another speciality from the highlands. Food can speak to a people’s taste and regional differences and signal a connection to culture and national pride.

For Asian cooking aficionados, Stutong Community Market is the place to go to source uncommon ingredients for traditional dishes. Available here is a wide variety of the bounty of the South China Sea, as well as a variety of fruits and vegetables cultivated, foraged, or imported. The range of products extends to local grocery items from other parts of Sarawak and ethnic cakes, puddings, and pastries. Cooked food and hawker stalls are conveniently located on the first floor (and you can even have your clothes tailored here!).

Sarawak has developed its own distinctive culture, different to what you would find in peninsula Malaysia. The geographical location of these two capital cities, separated by the South China Sea, has similarities and dis-similarities. Visit this City of Unity and Gastronomy for a comparative appreciation of Kuala Lumpur and Kuching.

Edited by Dr Louise Macul

Special thanks to:

- Dr. Louise Macul for taking us on a tour of the Borneo Cultures Museum and unstintingly sharing her knowledge, and articles in dayakdaily.com

- Edward Mansel who took us on a walking tour on the trail of the White Rajahs. An octogenarian, he has witnessed an exciting part of Sarawak’s history. The walking tour ended with a driving tour!

- Janet Rata Noel who took us through the Tun Jugah Foundation galleries.

- My friend of many years, Melinda Siew, her husband Kenny, mum Margaret and sons Keegan and Kaedan whose hospitality made our visit so comfortable. Margaret drove us to Stutong and all over Kuching south, and to Petra Jaya, from the airport and to the airport, unceasingly pointing out landmarks along the way, along with interesting snippets of people, places and things unique to Sarawak.

- Fellow Museum Volunteer JMM, Noriko Nishizawa, for her companionship and care throughout the trip.

References

- Munan, Heidi (2015) Sarawak Historical Landmarks

- Lim, Jerome. (7 July 2012). St. Joseph Cathedral, Kuching. The Long and Winding Road Blog. https://thelongnwindingroad.wordpress.com/

- Sarawak witnesses remarkable progress: Poverty rate reduced to 9 pct, major infrastructure projects underway: https://dayakdaily.com/sarawak-witnesses-remarkable-progress-poverty-rate-reduced-to-9-pct-major-infrastructure-projects-underway/

- Bario rice – a rare grain: https://www.theborneopost.com/2012/01/29/bario-rice-a-rare-grain/

- Kuching division starts Sarawak’s journey of progress: https://themalaysianreserve.com/2021/01/20/kuching-division-starts-sarawaks-journey-of-progress/

- “Kuching, Malaysia” in the Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/place/Kuching

- Ting, John H.S. (2018). The History of Architecture in Sarawak before Malaysia. Kuching: Pertubuhan Arkitek Malaysia Sarawak Chapter.

- Kuching in Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kuching

Interesting and informative.