By Emna Esseghir

Introduction

God is beautiful and He loves beauty.

— Tradition (hadith) of the Prophet Muhammad from Sahih Muslim

Within the Islamic theological framework, a core tenet asserts that God possesses the attribute of beauty, and this inherent beauty finds manifestation in His creations. It is a frequently reiterated notion that God is intrinsically beautiful, and He exhibits an affinity for aesthetics and beauty. This theological premise underscores the significance of aesthetics, harmony, and beauty across diverse facets of Islamic culture, encompassing art, architectural design, and the ethical comportment of individuals.

The concept that God cherishes beauty is intrinsically associated with the idea that human beings are encouraged to both recognise and cultivate beauty in their actions and environmental milieu. This is prominently exemplified in the rich artistic and architectural traditions of Islamic civilisation, wherein intricate designs, eloquent calligraphy, and geometric patterns are judiciously employed to embellish religious edifices, palatial structures, and various other architectural forms.

One of the major elements used to express this beauty in Islamic art was wood carving.

1. What is wood carving?

Wood, as the most abundant natural resource, has historically captivated the attention of humankind. Intriguingly, in numerous regions of the Islamic world, wood is relatively scarce, yet it enjoys a distinguished status and necessitates a high degree of craftsmanship. Within the context of Islamic art and architectural construction, woodcarving emerges as a prominent technique, particularly in the context of mosque construction. This art form exerts a profound influence, elevating the aesthetic appeal of these religious edifices while imbuing them with profound symbolism.

Woodcarving, at its core, entails the intricate creation of designs in wood, achieved through manual dexterity and specialised carving implements. The array of motifs ranges from the intricate and traditional to geometric precision or abstract patterns. A pivotal preliminary step in woodcarving involves the meticulous identification of the wood’s grain and texture before embarking on the carving process. The resulting carved elements consistently manifest in an abstract fashion, representing botanical elements or geometric configurations and can be categorised into three distinct architectural components: structural, elemental, and ornamental.

Woodcarving serves as both a technique and a final product, in which wood is meticulously shaped into decorative and artistic forms. Wood, as a widely accessible and sustainable resource, is available in diverse sizes suitable for crafting objects of various scales, from minor artefacts to grand architectural structures. Its intrinsic robustness enables it to bear substantial loads and span extensive areas. Furthermore, wood is amenable to manipulation by a judicious application of manual labor and lends itself readily to precision shaping using rudimentary hand tools. Its innate spectrum of colors, tonal nuances, and susceptibility to diverse surface treatments enhance its allure, rendering it an aesthetically pleasing and adaptable material.

2. Historic evolution of wood carving art in the Islamic world

Undoubtedly, the artistic evolution of wood carving among Muslim artisans during the formative centuries of Islam constitutes a remarkable historical and artistic phenomenon. This creative metamorphosis was profoundly molded by the convergence of Hellenistic (in the eastern Mediterranean and Middle East, the period between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE and the conquest of Egypt by Rome in 30 BCE) and Sassanian artistic influences (officially known as Eranshahr was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th–8th centuries AD).

The amalgamation of these disparate traditions ignited the development of a distinctive Islamic wood-carving style that left an enduring imprint on the artistic panorama of the Islamic realm.

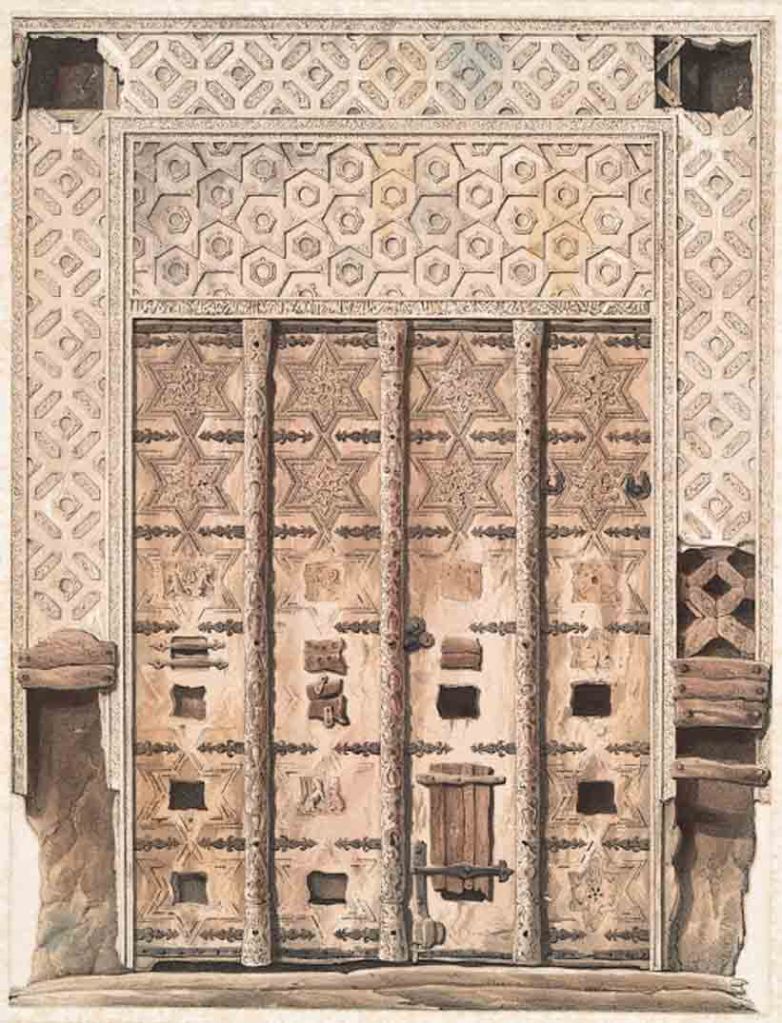

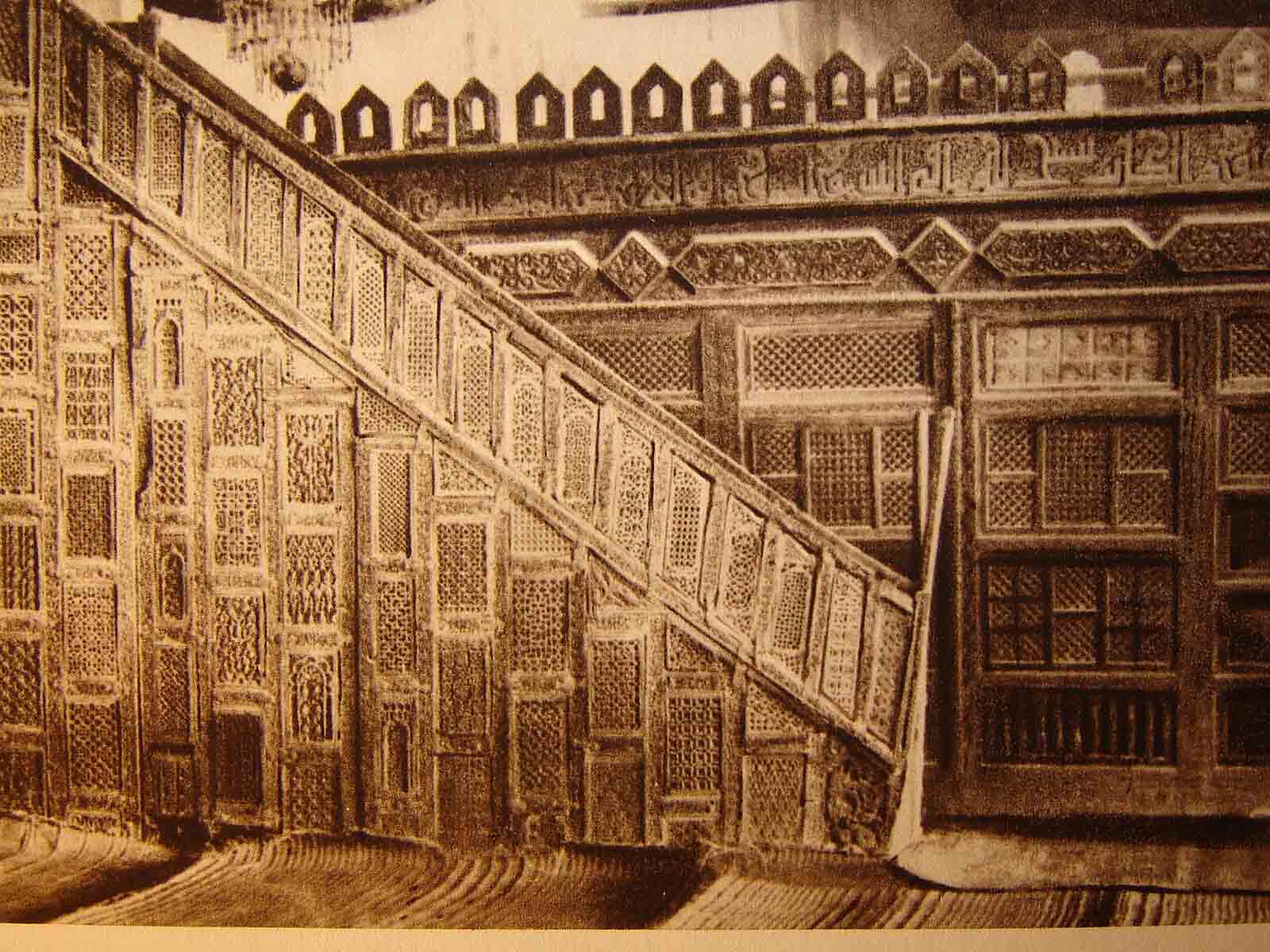

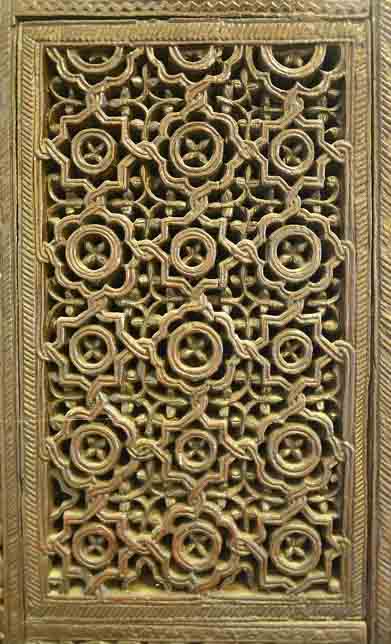

A prominent exemplar of early Abbasid wood carving, symbolising the culmination of these influences, resides in the prayer pulpit enshrined within the Qairawan mosque in Tunisia. This masterful creation, likely transported from Baghdad during the third/ninth century under the patronage of influential figures from the Aghlabid dynasty, stands as an epitome of wood-carving craftsmanship affiliated with the Baghdad School.

Adorned with meticulously crafted panels featuring geometric motifs and designs, it is believed to have been commissioned during the reign of Harun, the Abbasid Caliph.

This architectural marvel remains a source of inspiration for contemporary abstract art, serving as a testament to the enduring relevance of its patterns and designs.

An old postcard (1900) showing the carved teak

Minbar and the Maqsura. Photo source: Wikimedia

The intricate detailing of the minbar.

Photo source: Issam Barhoumi- Wikimedia

Over time, Abbasid artists developed their own unique style, breaking away from the artistic traditions of the Sassanian and Hellenistic periods. This new Abbasid style became popular among Egyptian craftsmen during the Tulunid era (935-969), especially in Cairo.

As the Abbasid artistic style matured, Egyptian craftsmen refined it further, creating a distinctive artistic expression by the 10th century. They began carving deeper and creating more rounded shapes, showcasing their creative skills.

Assessing how Egypt’s rich heritage of crafts and arts influenced the advancement of wood-carving by Egyptian artists is a complex task. Egypt’s legacy offered fertile ground for innovation, contributing to the mastery of Egyptian wood carving.

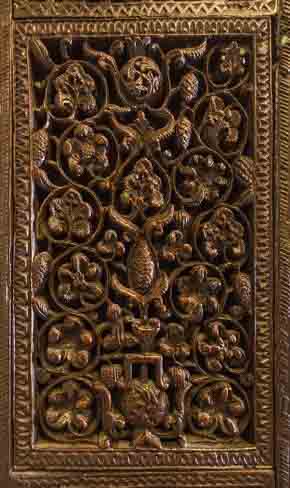

Over time, geometric patterns gave way to different forms of decoration, like intricate carvings of animals and arabesque scrolls. These works demonstrated the artists’ meticulous attention to detail, combining technical expertise and hard work.

During the Fatimid era, some wood panels stood out for their exquisite artistry. They portrayed typical Egyptian scenes, with a strong focus on birds and animals, reflecting the ancient Egyptian tradition of revering specific animals as deities, adding a cultural dimension to the wood carvings.

In the Ayyubid period, the influence of the Fatimids continued in wood carving, with arabesque scrolls becoming more intricate. The use of nasj script instead of Kufic inscriptions reflected evolving artistic tastes. This period also saw a greater commitment to intricate detailing, emphasising the dedication of the artists.

Panel with Inscription probably 13th century

Photo source: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/448499

In Egypt, wood carving reached its peak over time but gradually declined in the 15th century, marking a significant turning point in its evolution.

Conversely, in Iran, wood carving was mature even during Mahmud of Ghazni’s rule during Ghaznavide empire. A preserved door from his tomb in the Agra Museum demonstrates the innovative approach of Iranian artists, characterised by deep undercutting and multiple planes, showcasing an Iranian stylistic imprint.

Gates of the tomb of Mahmud of Ghazni, (James Atkinson in 1842)

Although there are relatively few wood carvings from the Saljug period, it’s reasonable to believe that artists in Asia Minor during the 12th and 13th centuries crafted exceptional works, resonating with the quality seen in Egypt and Syria.

Wooden Sarcophagus from the Seljuk Period

the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art in Istanbul.

Photo source: https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo/seljuq-period.html?sortBy=relevant

While wood carvings from the early Mongol period are scarce, historical evidence suggests that Iranian artists in Western Turkestan achieved remarkable technical perfection in the 14th century. The zenith of wood carving persisted during the Safavid period, although signs of decline appeared in the 17th and 18th centuries. During this era, panels transitioned from intricate carving to painting and lacquering, marking a transformative phase in the history of Islamic wood carving.

Wood carving from Safavid Period. Photo source: Hayk – Wikimedia

3. Wood carved artefacts with Islamic influence at the National Museum

The practice of traditional Malay wood carving represents a seminal facet within the domain of Malay cultural heritage, encompassing profound and substantive cultural importance.

It predates the arrival of Islam, but since the adoption of Islam as the religion of the Melaka Sultanate, we can distinguish some specific characteristics:

• Integration of Arabic Calligraphy: A defining feature of Malay wood carvings within Islamic art is the sophisticated integration of Arabic calligraphy. These carvings frequently incorporate Quranic verses or excerpts from Islamic texts, meticulously inscribed with exceptional finesse. The utilisation of calligraphy transcends mere ornamental aesthetics; it serves as a conduit for the visual representation of sacred Islamic scripture, infusing these wooden artefacts with profound religious significance. The interplay of script styles, such as Kufic or Naskh, further underscores the artistic and spiritual dimensions of these carvings.

Doors panels inscribed with Quranic verses, on display at

Gallery B, National Museum. Photo source: Emna Esseghir

Wooden panel with sentence from the Holy Quran used to

decorate a muslim chapel, on display at Gallery B, National Museum.

Photo source: Emna Esseghir

The Setul palace door, displayed at Gallery B, National Museum.

Photo source: Maganjeet Kaur

• Harmonious Synthesis of Malay and Islamic Aesthetics: A salient feature of these carvings is their ability to harmoniously blend indigenous Malay motifs with Islamic artistic elements. This synthesis culminates in a unique visual language that encapsulates the multifaceted cultural identity of the Malay-Muslim community. By seamlessly interweaving Malay flora for example with Islamic motifs, these carvings offer a nuanced expression of both regional and religious identities, emphasising their role as cultural artefacts and religious conveyors.

Wooden panel with flora and sentence from the Holy Quran,

on display at Gallery B, National Museum. Photo source: Emna Esseghir

To conclude, Arabic Calligraphy meticulously inscribed with Quranic verses adds profound religious significance, while geometric precision reflects metaphysical themes. The harmonious synthesis of Malay and Islamic aesthetics highlights cultural identity. But beyond aesthetics, these carvings serve functional roles in Islamic architecture, enhancing sacred spaces and connecting the physical and spiritual realms. In essence, Malay wood carvings contribute significantly to the artistry and spirituality of the Malay-Muslim heritage.

References

A Study of Woodcarving Motifs on Traditional Malay Houses in Kuala Pilah, Negeri Sembilan: https://melaka.uitm.edu.my/ijad/images/PDF/1.pdf

DEVELOPMENT OF MALAY WOOD-CARVING MOTIFS FROM ISLAMIC PERSPECTIVES: https://oarep.usim.edu.my/jspui/bitstream/123456789/14524/1/4.BI.%20SAIS2021%20-%20Development%20Of%20Malay%20Wood-Carving%20Motifs%20From%20Islamic%20Perspectives.pdf

Fatimid Wood-Carvings in the Victoria and Albert Museum: https://www.jstor.org/stable/862433

Gates of the tomb of Mahmud of Ghazni, by James Atkinson in 1842: https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gates_of_the_tomb_of_Mahmud_of_Ghazni,_by_James_Atkinson_in_1842.jpg

JULFA i. SAFAVID PERIOD: https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/julfa-i-safavid-period

Panel with Inscription: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/448499

The Islamic Art of Wood Carving: Exquisite Patterns on Furniture and Decorative Objects: https://russia-islworld.ru/en/kultura/the-islamic-art-of-wood-carving-exquisite-patterns-on-furniture-and-decorative-objects-2023-08-01-34970/

Wooden Sarcophagus from the Seljuk Period: https://etc.usf.edu/clippix/picture/wooden-sarcophagus-from-the-seljuk-period.htm