By Emna Esseghir

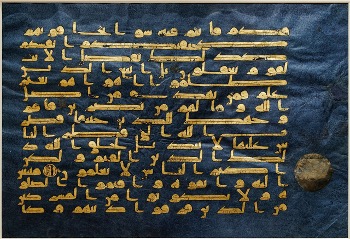

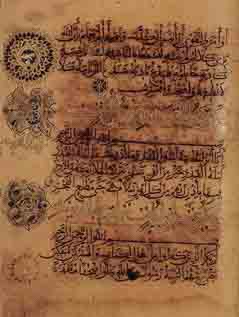

Leaf from the Blue Quran of Tunisia showing Sura 30: 28–32, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Human is Social by Nature

Ibn Khaldun, the distinguished Tunisian historian and scholar, expounded in his seminal work, the “Muqaddimah,” the profound idea that humans innately gravitate towards forming social groups, tribes, and communities. He persuasively argued that these intrinsic social bonds not only define our human nature but also serve as the bedrock for the development and sustainability of entire civilizations. This notion of social cohesion finds resonance in our broader human proclivity for connectivity, which echoes resoundingly throughout history.

The fascinating evolution of human communication further underscores our fundamental need to express and safeguard knowledge. This captivating journey commenced with rudimentary visual storytelling through cave paintings and progressively evolved into more structured forms of writing, including early pictograms and ideograms etched in cuneiform and hieroglyphics. As human societies advanced, the emergence of abstract scripts, epitomized by the Phoenician alphabet, substantially enhanced the efficacy of communication. The pinnacle of this progress was reached through the artistry of calligraphy, where skilled artisans elevated writing into a form of visual expression. Through the medium of calligraphy, they crafted exquisite manuscripts, sacred texts, and official documents, eloquently illustrating our unwavering commitment to conveying ideas, sharing wisdom, and etching an enduring legacy on the tapestry of human history.

To explore the captivating world of Arabic calligraphy, which serves as a testament to the beauty of written expression, In this article, I will explore the history and evolution of Arabic calligraphy. Additionally, I will elucidate various aspects of Arabic calligraphy exhibited within the Muzium Negara.

What’s Arabic Calligraphy?

Based on the definition given by the Unesco, Arabic calligraphy is the artful practice of elegantly writing Arabic script, aiming to convey a sense of harmony, grace, and beauty. This tradition, passed down through both formal and informal educational channels, involves the skillful arrangement of the twenty-eight letters of the Arabic alphabet in a flowing, cursive style, typically from right to left. Initially designed to enhance the legibility of written text, it gradually evolved into a revered form of Islamic Arab art, applicable to both traditional and contemporary works. The flowing nature of Arabic script offers endless creative possibilities, allowing letters to be elongated and transformed in various ways to create diverse visual patterns.

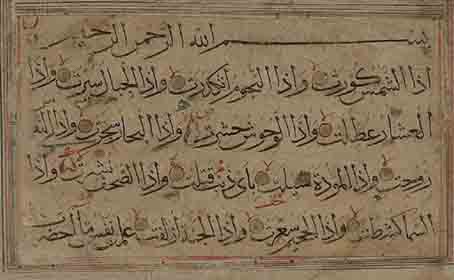

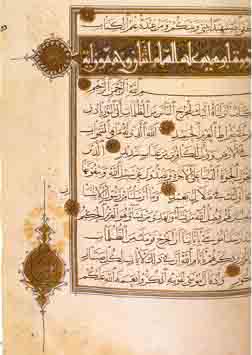

Text from a 14th century Quran written in the Rayhani script

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Traditional techniques employ natural materials like reeds and bamboo stems as writing tools, while ink is meticulously crafted from a mixture of honey, black soot, and saffron. The paper used is handmade and treated with starch, egg white, and alum. In contrast, modern calligraphy frequently employs markers and synthetic paints, and spray paint becomes the medium of choice for calligraffiti, which adorns walls, signs, and buildings. Artisans and designers utilize Arabic calligraphy to enhance various art forms, including marble and wood carving, embroidery, and metal etching.

Origins of Arabic Calligraphy

The pre-Islamic period in the history of Arabic calligraphy was characterized by a relatively rudimentary form of the Arabic script. During this time, the Arabian Peninsula was home to various tribal communities, and the Arabic script, which had evolved from the Nabatean script, was used primarily for practical purposes such as inscriptions and basic record-keeping.

Map of the Roman empire under Hadrian (ruled CE 117–138), showing the location of the Arabes Nabataei in the desert regions around the Roman province of Arabia Petraea

This script had a limited number of characters and was written from right to left. Over time, as the Arabian Peninsula became more interconnected through trade and cultural exchange, the script began to evolve to accommodate the Arabic language.

In pre-Islamic Arabia, the primary means of communication and cultural preservation was through oral tradition. Poems and stories were passed down orally from one generation to the next. Writing was less developed, and the use of the Arabic script was limited mainly to practical purposes such as inscribing names, tribal markings, and important declarations on stones and other surfaces.

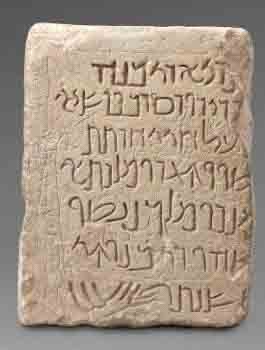

Examples of Nabataean inscriptions from Petra (Source: https://www.swissinfo.ch/spa/multimedia/tras-las-huellas-de-scheich-ibrahim_petra–esplendor-del-desierto/34695166)

The early Arabic script bore the influence of neighboring scripts like Aramaic and Syriac, evident in some of the shapes and characters present in early Arabic inscriptions.

These initial instances of Arabic script dating from that era are observable in inscriptions on pre-Islamic artifacts, including tombstones, coins, and the foundations of structures. These inscriptions tended to be straightforward and pragmatic, serving functional purposes rather than showcasing the artistic finesse associated with calligraphy.

It’s worth highlighting that the development of Arabic calligraphy as a refined and artistic tradition occurred later, coinciding with the rise of Islam. The Quran, revealed to the Prophet Muhammad, played a pivotal role in elevating the Arabic script to a higher status. This transformation ultimately gave rise to the diverse calligraphic styles and forms that we now associate with Arabic calligraphy.

Arabic Calligraphy’s Zenith

The early development of Arabic calligraphy represents a captivating narrative of artistic evolution that defies linear progression. Across geographically dispersed regions like Damascus, Baghdad, Morocco, and Spain, a rich tapestry of scripts flourished and waned in popularity. Among these, Kufic, originating from the city of Kufah in Iraq, emerged as the initial universal script, holding sway over Arabic calligraphy from the 7th to the 11th century. However, during this early period, Kufic retained a certain ruggedness and lacked the systematic refinement that would characterize its later incarnations during the “Golden Age” of calligraphy.

The turning point in the journey of Arabic calligraphy arrived in 762 when the Abbasid Caliph Mansur embarked on a grand endeavor—the construction of Baghdad, a meticulously planned city positioned strategically along the banks of the Tigris River. Baghdad swiftly ascended to the status of the cultural nucleus of the Middle East, attracting scholars, artists, and intellectuals from far and wide. It was in this vibrant and intellectually charged atmosphere that Arabic calligraphy reached its zenith of development.

This illustrious “Golden Age” of Arabic calligraphy is often epitomized by the contributions of three iconic calligraphers:

1- Ibn Muqla (886–940) introduced groundbreaking principles of proportion and aesthetics to the art, elevating it beyond mere utility.

2- Ibn al-Bawwab (believed to have lived from 961–1022) pushed the boundaries of script and composition, further enhancing the art’s visual appeal and complexity.

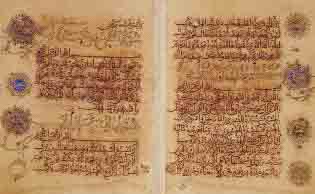

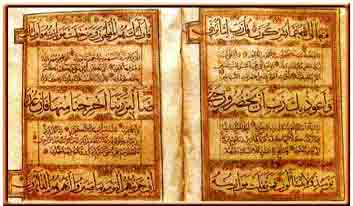

Two folios of the Quran, written by Ibn al-Bawwab in 1001 CE. The original copy is preserved in Chester Beatty Library, Dublin (Credit: Chester Beatty Library, Dublin)

A folio from the Quran written by Ibn al-Bawwab (Chapter 971 Al-Qadr and Chapter 98: Al-Bayyinah) (Credit: Chester Beatty Library, Dublin)

3- Yakut al-Musta’simi of Amasya (d. 1298) left an indelible mark with his intricate and ornate calligraphic works, exemplifying the pinnacle of the craft.

A folio of the Quran, written by Yaqut al-Mustasimi, preserved in Topkapi Saray Library, Istanbul

Two folios from the Quran, written by Yaqut al-Mustasimi in 1269 CE, are preserved in Khuda Bakhsh Library, Patna, India

In this era, Arabic calligraphy transcended mere writing; it became an art form that harmoniously blended form, function, and artistic expression. It was not merely a conduit for conveying words but a source of visual beauty and cultural significance.

The “Golden Age” of Arabic calligraphy refined the art to such an extent that it continues to inspire admiration and scholarly inquiry, standing as a testament to the enduring marriage of creativity and tradition. This legacy endures in the intricate and elegant calligraphic works that grace Islamic architecture, manuscripts, and various forms of artistic expression today.

4- Arabic Calligraphy different style

Arabic calligraphy encompasses an array of script styles characterized by cursive forms, vertical extensions, and intricate geometric designs. Some scripts adopt more pronounced curves and intricate linkages between letters. Each style of Arabic calligraphy serves a distinct purpose, tailored to the specific intentions of the calligrapher.

Same sentence written in 12 different styles

(Source: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/321514860892971724/)

5- Examples of fusion with the Arabic Calligraphy:

Here are photos of several buildings, ceramics, weapons, and artefacts adorned with Arabic calligraphy. They come in various forms and styles, usually designed to convey moral messages through Quranic verses.

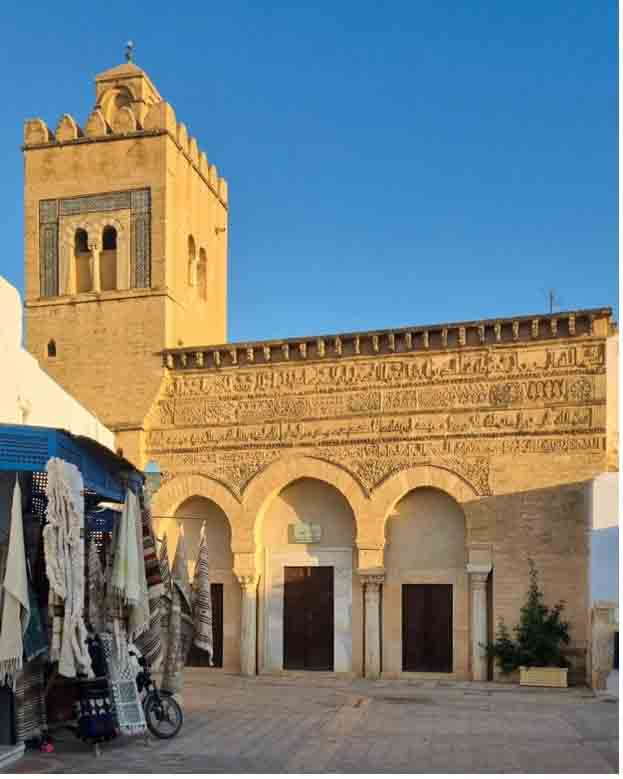

Facade of Mohamad Ben Khairoun El Maarefi’s Masjed in Kairouan – Tunisia With Kufi Script (Photo: Issam Barhoumi)

Calligraphic mosaic, Iran

(Source : https://www.sciencephoto.com/media/83654/view/calligraphic-mosaic-iran)

Ottoman Sword By Ahmad Al Khurasani with Arabic calligraphy, exhibited at IAMM (Photo: Emna Esseghir)

Aceh plate with Arabic calligraphy exhibited at Islamic Arts Museum, Malaysia

(Photo: Emna Esseghir)

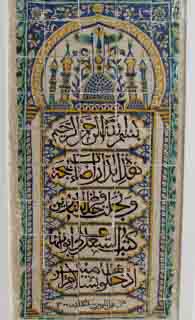

Tiles with Quran verses exhibited at Bardo Musuem Tunisia

(Photo: Mohamed Yazid Ben Abdessalem)

The Kaaba’s gold laced cover

(Photo: Sami Mansour)

The calligraphic inscription between the zigzag designs and medallion reads: Blessings to Allah and praise be to Him, Blessed be Allah the Great, Oh, Lord who give us riches, There is no God but Allah and Prophet Muhammad is the Messenger, Surah al-Baqarah (2:144), and Oh, Sultan.

Red vest with verses displayed in Gallery B, Muzium Negara

(Photo: Emna Esseghir)

*woodcarving is influenced by the moral ethical values with Quranic verses:

Wood carved plates, Gallery B Muzium Negara

(Photo: Emna Esseghir)

Persian or Iranian Brass Islamic Magic Bowl, Gallery B, Muzium Negara

(Photo: Emna Esseghir)

References

- Blue Quran: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue_Quran

- THE MUQADDIMAH by Abd Ar Rahman bin Muhammed ibn Khaldun: https://delong.typepad.com/files/muquaddimah.pdf

- Arabic calligraphy: knowledge, skills and practices: https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/arabic-calligraphy-knowledge-skills-and-practices-01718#:~:text=Arabic%20calligraphy%20is%20the%20artistic,cursive%2C%20from%20right%20to%20left

- A Brief History of Arabic Calligraphy: https://www.skillshare.com/en/blog/a-brief-history-of-arabic-calligraphy/

https://www.metmuseum.org/learn/educators/curriculum-resources/art-of-the-islamic-world/unit-two/origins-and-characteristics-of-the-arabic-alphabet - Ibn Muqla: https://artcalligraphy.net/en/ibn-muqla/

- Ibn Muqla: The prophet of Arabic Calligraphy by Md. Monirul Islam: https://ocd.lcwu.edu.pk/cfiles/Arabic/Min/FA-101/IbneMakla.pdf

- Hasan Celebi, Turkey’s Master Calligrapher by Professor A. R. MOMIN: https://www.iosminaret.org/vol-8/issue21/Hasan_Celebi.php

- Arabic Calligraphy Styles: https://www.arabic-calligraphy.com/arabic-calligraphy-styles/

- Some Islamic Artefacts at Muzium Negara: https://museumvolunteersjmm.com/2020/04/01/some-islamic-artefacts-at-muzium-negara/