by Manjeet Dhillon

A group of Museum Volunteers (MV) gathered bright and early on a Tuesday morning, 19 November 2024, to explore the National Textile Museum’s special exhibit, Telepuk: The Art of Gold Leaf (Pesona Telepuk: Seni Perada Emas). Adding to the buzz of the day, a telepuk-making workshop was in full swing, with our very own MV’s Hani and Farah, rolling up their sleeves and getting hands-on with the craft.

MV group photo, taken by Kulwant Kaur

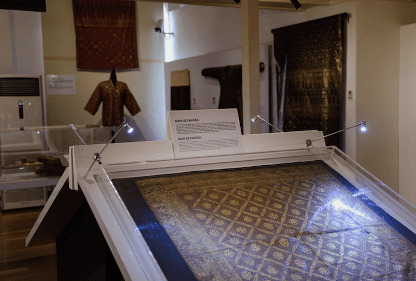

Puan Salmiah ushered us to Gallery Saindera, where the textile exhibit is being showcased from 28 October to 31 December 2024. It’s divided into five segments, showcasing a whopping 183 collections. Among these, you’ll find 49 stunning examples of telepuk textiles, 130 intricately designed telepuk stamps, and a handful of manuscripts and publications that tie it all together.

In ancient Malay literary texts, telepuk originally referred to a type of lotus, the nymphaea stellata. Over time, the word became closely tied to the textile itself. Some believe it refers to the floral stamps used in the process, while others think it describes the shimmering golden patterns on the fabric, reminiscent of sunlit lotuses glistening on a calm lake. (https://telepuk.com/history/)

The first segment focused on the history of telepuk. This traditional technique involves creating motifs and designs on fabric, especially woven cloth, using a stamping technique with gold leaf. Artisans stamp Arabic gum onto the forearm, followed by the telepuk stamp carved with motifs. The gum acts as an adhesive for the gold leaf, which is then pressed onto the fabric. Kulwant asked why the forearm is used, and Puan Salmiah explained that its temperature is ideal for stamping. If the forearm isn’t used, the thigh is the alternative.

The table below highlights the diverse names and practices of telepuk in Malaysia, Indonesia, and Korea, emphasising its royal connections and the use of gold leaf in textile decoration.

| Country | Name | Details |

| Malaysia | Telepuk / Kain Serasah | Uses 24k gold leaf (often imported from Thailand) and is applied on woven fabrics like limar and satin, but not songket, as the latter already incorporates gold threads, making the combination visually excessive. Note: Gold leaf is imported from Thailand for its superior quality. It is produced in Thailand because it is traditionally used in the royal attire of the King of Thailand. |

| Indonesia | Perada | Shares similarities with telepuk; the exact application and materials may vary. |

| Korea | Gyumbak | Reserved for royalty (Joseon Period, 1392~1910), often adorning fine textiles with gold leaf or foil. |

| Sri Lanka | Use gold water instead of gold leaf | |

| India | Varak | In Rajasthan, particularly in Jaipur, Sanganer, Jodhpur, Sawai Madhopur, and parts of Gujarat, artisans practise a technique called varak, where delicate sheets of gold leaf, known as patra, are adhered to textiles. This is done using a special glue called safeda or saresh, made from powdered resin. A later variation, known as khari, uses gold powder instead of leaf, giving the textiles a slightly different but equally striking effect. |

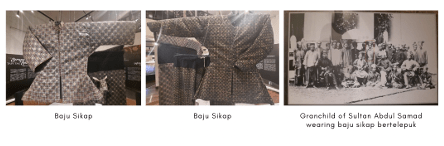

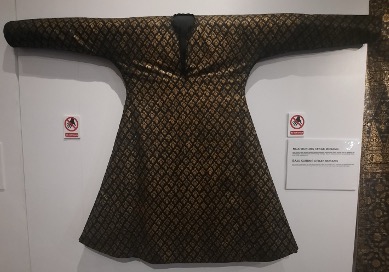

Among the displays was Sultan Abdul Hamid’s baju sikap, an outer garment worn over baju melayu, adorned with telepuk and featuring five gold buttons, typically a baju sikap has only one button. This piece was worn during King George V’s installation ceremony in 1911. Another was a baju sikap decorated with telepuk, belonging to Sultan Abdul Samad, the fourth Sultan of Selangor. Estimated to be 170 years old, this garment was also featured in a photo of his grandchild wearing it. Sultan Iskandar of Perak was also known to wear a headdress made of telepuk, while the late Sultan Hishamuddin of Selangor donned a baju layang, a cape-like garment that forms part of Selangor’s royal dress code.

We learned that telepuk was especially prominent in states like Selangor, Pahang, Terengganu, Perak, and Johor. Its historical significance is captured in Malay manuscripts such as Syair Siti Zubaidah Perang Chik, where it is referred to as perada.

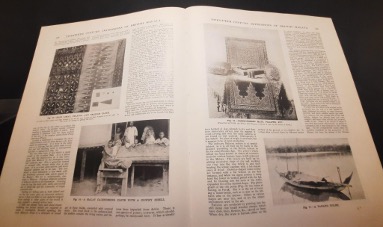

The exhibits also included a fascinating reference to The Malays: A Cultural History by R.O. Winstedt, which documented telepuk production in Pahang and Pattani. The book describes the process as practised in these regions, as well as in Selangor, noting its similarities to a technique from the state of Punjab, India. (excerpt from book: Patani, Pahang and Selangor produce cloths (kain telepuk) guided by a technique practised also in the Punjab. Cotton with a small pattern on a dark green or dark blue ground is polished (with cowry shells), stamped with armed wooden blocks that have been smeared with gum, and then covered with gold leaf that adheres to the gummy pattern.)

Twentieth Century Impressions of British Malaya: A historical reference capturing the art of telepuk, offering a glimpse into its cultural significance.

We now moved on to view collections, starting with one from Selangor. This piece stood out with its motifs of flora, fauna, and calligraphy. There’s even a section featuring the mirror image of a calligraphy inscription saying Bismillah ir Rahma ir Rahim (In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful), as well as Allah Muhammad, in a mirrored script. The designs aren’t just limited to nature and words, cosmic and geometric patterns also make appearances.

Kain telepuk with a mirror image of a calligraphy inscription saying Bismillah ir Rahma ir Rahim. Image source: www.https://tangankraf.com/

Baimi asked about the function of kain setangan, and Puan Salmiah explained that it’s folded into a headpiece for men, known as a tengkolok or tanjak. Kulwant chimed in, remarking how each wooden carving of the motifs is painstakingly detailed – definitely a lot of craftsmanship and precision goes into making these pieces!

A piece of sarong cloth from the collection of the late Tan Sri Mubin Sheppard was on display, donated by his wife to the legendary craftsperson Norhaiza Nordin. Each kain sarong is usually split into three parts:

- Kepala (head of the cloth), often placed at one end of the sarong. It serves as a focal point when the cloth is worn or displayed. For the sarong cloth below this is where the motif is made up of two types of pucuk rebung (bamboo shoot): one with bamboo shoots, the other floral.

- Tepi hati tengah (middle of the cloth), this central section connects the kepala and kaki kain. It usually contains repeating patterns or simpler motifs to complement the boldness of the kepala.The sarong below features scattered flowers and a mangosteen motif.

- Kaki kain (end of the cloth), this is the bottom or border of the fabric. It often features a band of more intricate or bold designs, framing the entire sarong.

From the collection of the late Tan Sri Mubin Sheppard

The MVs were further amused to learn that where you place the kepala kain on a woman’s attire actually symbolises her marital status! If it’s at the back, she’s married. In the front means she’s single, to the left is a divorcee (janda), and to the right is a widow (balu). The same idea applies to the samping worn with the baju Melayu: below the knee means the wearer is married, while above the knee signals they’re single.

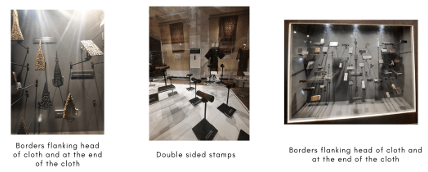

Moving on, we took a look at the stamps used to create the motifs. The main design we saw was a scattered flower pattern, and the stamps are typically made from kayu jelutong or kayu celah wood. Hani pointed out that some of the stamps had a metal-like top, which Puan Salmiah explained is a unique feature of a few stamps, but traditionally, they’re carved entirely from wood. The stamps on display, provided by the Department of Museums Malaysia, included both traditional ones and some whose origins could not be traced to a specific state.

Gold leaf is applied on these stamps to create the telepuk effect. The second vitrine featured stamps used for the kepala kain, often showcasing the pucuk rebung (bamboo shoot) design. We were all amazed by the intricacy of these carvings—each one carefully polished and varnished to a gleam. Next, we saw stamps for the tepi hati tengah section of the cloth, featuring a flower-in-a-box design. There were also stamps for bunga inti, smaller flowers placed between the pucuk rebung.

Continuing, we found stamps for the borders and kaki kain, known as sikat kain (comb stamps). These had more geometric, fence-like motifs (pagar istana) and some featuring awan larat (cloud patterns), ombak ombak (waves), and ulam raja (herbs).

One particularly special vitrine had double sided stamps, making it easier for the craftsman to switch from one side to the other when working on the telepuk design. This collection used both metal and wood.

MV Kulwant asked if these materials are still available for sale, and Puan Salmiah mentioned that Adiguru Norhaiza Nordin in Besut, Terengganu, would have some pieces for sale, as well as Gerakan Langkasuka.

We then explored the kebaya, where the gold leaf motif featured bunga kamunting cina. There was also a kain lepas(unstitched cloth) on display, typically used as a shawl or to cover one’s head. This was an example of wrap ikat (ikat tenun loseng) that incorporated telepuk. We also saw weft ikat pieces, like ikats limar, kebaya, and kain sarong (which didn’t include the tepi hati tengah motif).

One of the highlights was a pantaloon decorated with gold leaf. Then, we came across a 19th-century baju kurung cekak musang, covered in a full floral pattern. It’s said that it takes anywhere from 6 months to a year to complete the full telepuk pattern on such a piece. Most of the collection is about 100 years old because telepuk production stopped after WWII, making this craft a dying art. But now, with efforts from the Gerakan Langkasuka, Yayasan Hassanah, and collaborations with the National Textile Museum, there are workshops and knowledge-sharing sessions to revive it.

Baju kurung cekak musang

Hani shared an interesting piece of history—back in the day, artisans would view their fabric printing as an offering to God. It wasn’t just a craft; it was a gift, a present that was made with deep care. This heart and soul commitment resulted in pieces that were beautifully straight and exquisitely crafted.

We also checked out the tools of the trade. There was a sample of the wood block used to carve telepuk stamps, made from cengal or jelutong wood. We saw a carving knife, as well as sketches by Adiguru Norhaiza Nordin and collections from the Department of Museums Malaysia.

We then looked at a Bugis cloth from Indonesia, which had a distinctive chequered pattern. The shiny finish comes from a calendering process known as gerus. Along with that, there were several examples of kain setangan featuring both calligraphy and floral motifs.

The third segment focused on the calendering process, with a detailed step-by-step explanation. A key element of this process is the use of siput bintang (cowry shells) as gerus. An exhibit demonstrated how the woven cloth is placed along a stick, with the bottom of the stick covered in cowry shells. The stick is then glided across the fabric, polishing it, enhancing its durability, and compressing the weaving yarns. Typically, one cowry shell can be used to calendar 2 to 3 pieces of cloth, each about 4 metres in length.

Before the gerus process begins, the woven cloth is washed with soap nuts (buah kerang) for pest control. The cloth is then dried, and a layer of wax is applied before the calendering process starts. This process can take up to a week, depending on the length of the cloth, after which the telepuk process can begin.

The telepuk process involves several materials: gold leaf, woven cloth, telepuk stamps, Arabic glue, and bamboo spatulas (used on the forearms). The process starts with applying Arabic glue to the forearms. Once the glue is in place, the telepuk stamp is pressed onto the forearm and then transferred to the fabric. After leaving it for a short while, the gold leaf is applied, and any excess is carefully brushed away with a fine brush.

We went upstairs for a showcase of carefully-selected collections from the Department of Museums Malaysia and exhibition partners consisting of state museums and individuals. Among them are collections of telepuk from the Terengganu Museum Board, Kedah Museum Board, Selangor Malay Customs and Heritage Corporation (PADAT), Johor Heritage Foundation and Mr. Norhaiza Noordin.

The final segment focuses on the sustainability of telepuk, featuring the latest creation: a long kebaya worn by Tengku Permaisuri Selangor, Tengku Permaisuri Hajah Norashikin, during her husband’s (9th Sultan of Selangor, Sultan Sharafuddin Idris Shah Alhaj) birthday in 2021. Recognising Selangor as one of the states renowned for telepuk, the Tengku Permaisuri is committed to uplifting and reviving this heritage in Selangor.

Our last insight highlights the traditional method of caring for textiles, known as wukuk kain. This special technique, akin to dry cleaning, involves placing the cloth over a basket, with a pot of incense burning beneath it. Pandan leaves, flowers, and sugar cane are added to the incense, emitting a fragrance that is transferred to the telepuk fabric. This process helps preserve the fabric’s colour and acts as a natural pest control measure.

As we concluded our exploration of the art of telepuk, we would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to Puan Salmiah for her invaluable insights and detailed explanations, which deepened our understanding of this traditional craft. A special thank you to all the artisans and curators who preserve and share these rich cultural legacies.

We left with a deeper appreciation for the artistry, history, and ongoing efforts to keep these traditions alive.

Reference:

National Textiles Museum

https://www.instagram.com/korea_heritage_geumbakjang/

Adiguru Norhaiza’s Story | Reviving the Forgotten Textile Art, Telepuk – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f-IO9_Z-CtI