By Shirley Abdullah

Dr. Saw Chaw Yeh is a Malaysian archaeologist specializing in prehistoric rock art and cultural heritage. She is the author of The Rock Art of Kinta Valley, a comprehensive examination of one of Malaysia’s most significant prehistoric art regions.

Rock art offers a profound glimpse into the lives, beliefs, and artistic ingenuity of ancient communities. According to Dr. Saw, the long-held belief that artistic expression originated in the West has been challenged by discoveries in Southeast Asia, particularly in Indonesia. Caves in Sulawesi and Borneo have revealed animal paintings and hand stencils dating back at least 40,000 years. These findings demonstrate that artistic expression flourished independently in multiple regions, contesting the Eurocentric narrative that art originated in Europe. This shift in perspective underscores Southeast Asia’s vital role in the history of human creativity, further evidenced by the abundance of prehistoric art found in Malaysia.

The Kinta Valley, located in central Perak between the Titiwangsa and Kledang Ranges, is rich in alluvial tin deposits and archaeological treasures. Excavations in its caves and rock shelters have uncovered human remains, stone tools, and pottery shards, indicating human activity spanning at least 10,000 years. Over time, these sites have served diverse purposes for various groups, including the Orang Asli, villagers, traders, and soldiers. Today, some caves have been repurposed as temples, while others face threats from quarrying activities.

Gua Tambun, a limestone rock shelter perched on a cliff in the Kinta Valley near Ipoh, is among Southeast Asia’s most extraordinary prehistoric rock art sites. It features over 600 paintings, providing a window into the lives and artistic expressions of ancient communities.

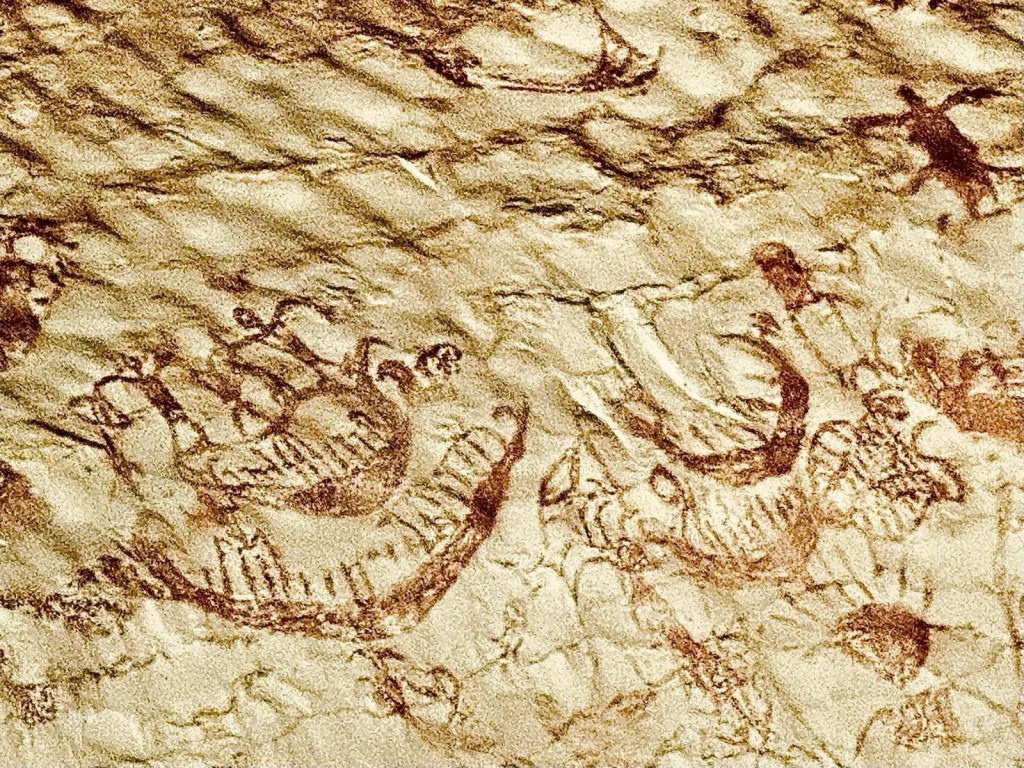

The vibrant reddish-orange hues of the paintings, derived from hematite, a natural iron oxide, stand out against the limestone surface. Ancient artisans ground hematite into powder and mixed it with water or organic binders to create durable pigments. The protective overhang of the cliff, combined with the enduring quality of these pigments, has preserved the artwork for millennia. The techniques employed reflect remarkable ingenuity, with fine lines and intricate details suggesting the use of brushes made from plant fibers or animal hair. Broader strokes may have been applied by hand or with pads. The sheer scale and positioning of the paintings, some located at significant heights, imply the use of scaffolding or ladders, indicating a deliberate effort and considerable skill in their creation.

Estimated to date back to the Neolithic period, the Gua Tambun rock art reflects a profound connection to nature and spirituality. The depictions include animals such as deer, tapirs, and fish, often portrayed in dynamic poses suggesting vitality. Human figures, typically shown in ritualistic postures, hint at communal activities or spiritual beliefs. Hand stencils, created by spraying pigment around a hand placed on the rock surface, add a personal dimension, symbolizing identity, community, or spiritual protection. The rare depictions of elephants stand out for their potential symbolic significance. In Southeast Asian traditions, elephants are often associated with power, wisdom, and memory, suggesting these images held special ceremonial or narrative importance.

Other Malaysian sites studied by Dr. Saw further reveal the diversity and complexity of prehistoric rock art. For example, Lumuyu Rock in Sabah, a sandstone outcrop nestled within dense rainforest, features intricate geometric patterns and stylized anthropomorphic figures. These abstract designs, characterized by interlocking lines and symmetrical forms, may carry ritualistic or cosmological meanings. For the local Dusun community and other indigenous groups, Lumuyu Rock remains culturally significant. Beyond its archaeological importance, it symbolizes ancestral heritage, often embedded in oral traditions that preserve community identity and history.

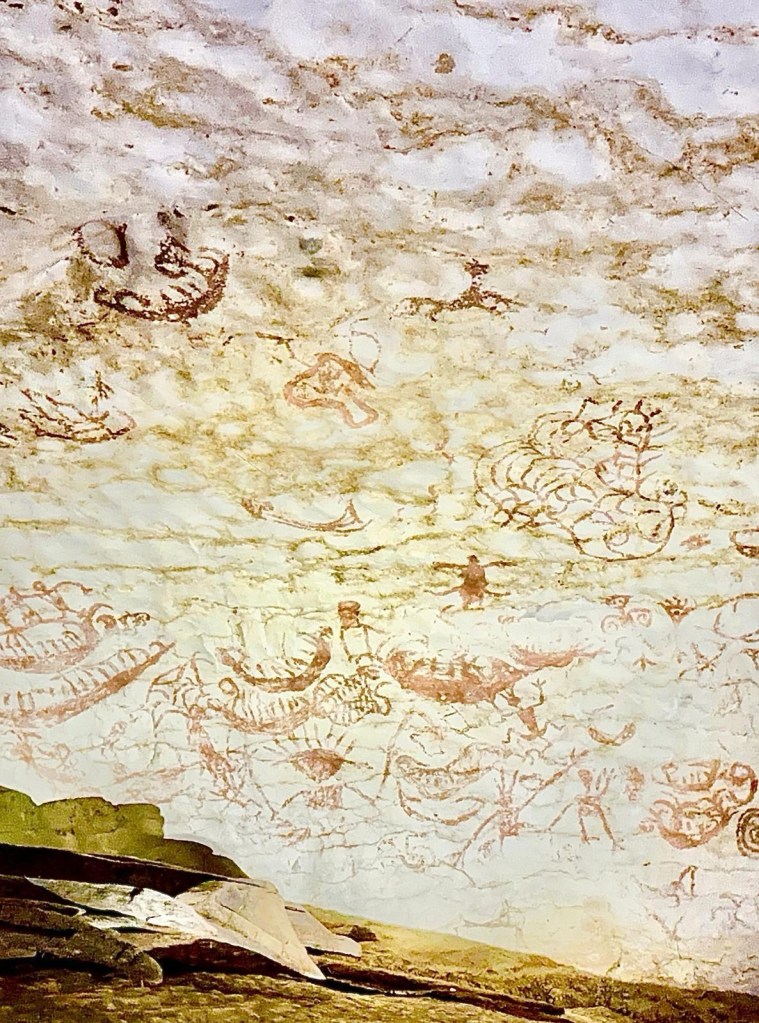

The Niah Caves in Sarawak contain rock art predominantly painted in red hematite, depicting anthropomorphic figures, boats, and abstract motifs. These images resonate with artefacts found within the caves, including boat-shaped coffins and canoe burials, underscoring the cultural and symbolic importance of boats as tools for travel, trade, and spiritual journeys.

Photos of cave art at NIAH CAVES, by courtesy of KAREN LOH

Photo of boat-shaped coffins and cave art at GUA KAIN HITAM, NIAH by courtesy of YUN TENG

The Pengkalan Kempas megaliths in Negeri Sembilan add another dimension to Malaysia’s prehistoric art. These standing stones, adorned with enigmatic carvings, likely served as burial markers or ceremonial artefacts. Their arrangement in clusters suggests a communal purpose, reinforcing their role as focal points of memory and identity. The three-dimensional nature of these carvings offers a contrast to the predominantly two-dimensional imagery of rock art, showcasing the diversity of artistic expression in prehistoric Malaysia.

The choice of specific locations for rock art is deeply rooted in phenomenology, a concept that explores human sensory experiences and interactions with the art, its location and the surrounding landscape. Many sites are near water sources, elevated vantage points, or within naturally sheltered areas, suggesting that their selection was purposeful and symbolic. The acoustics, light, and accessibility of these locations likely enhanced their ceremonial or communal significance. The positioning of Gua Tambun, overlooking the Kinta Valley, imbues it with prominence, likely making it a focal point for community gatherings.

Dating Malaysian rock art presents challenges, particularly in the humid, tropical environment, where organic pigments rarely survive, and weathering accelerates rock surface degradation. Direct dating methods, like radiocarbon analysis, are often impractical, leaving researchers to rely on relative dating techniques. These include stylistic comparisons with other Southeast Asian sites and the analysis of associated artefacts, such as tools or pottery. While current estimates suggest that the rock art at Gua Tambun dates back between 2,500 and 5,000 years, these remain approximations, highlighting the need for advanced, non-invasive dating methods tailored to tropical conditions.

Interpreting prehistoric rock art remains inherently complex. Abstract or ambiguous motifs defy straightforward identification. For instance, some animal depictions lack anatomical precision, prompting debates about whether they represent specific species, imagined creatures, or abstract symbols.

The ambiguity surrounding such depictions underscores a broader challenge in rock art interpretation. Dr. Saw suggests that the artistic choices of prehistoric communities may not have aimed at creating literal representations of their world. Instead, the motifs may have served symbolic, ritualistic, or narrative purposes, conveying meanings that are now largely inaccessible to modern observers.

Dr. Saw’s research identifies parallels between the motifs found in rock art and Orang Asli material culture, hinting at cultural continuity or shared symbolism. However, even these connections are difficult to substantiate fully. According to her, the only direct ethnographic evidence of rock art creators comes from the Lenggong Valley, Perak, where the Lanoh Negrito Orang Asli were historically associated with certain rock art. Dr. Saw deduced that earlier rock art depicting wild animals, large human figures, and geometric shapes aligns with the hunter-gatherer traditions found throughout Southeast Asia. However, determining the creators and meanings of rock art from later periods remains an elusive task .

The Kinta Valley, with its rich history of human occupation, illustrates this complexity. While traditionally inhabited by the Temiar and Semai Orang Asli, direct links between their material culture and the valley’s rock art remain unproven. Unfortunately, modern Orang Asli communities are generally unaware of the origins or meanings of these ancient artworks, reflecting the gradual loss of cultural connections over time.

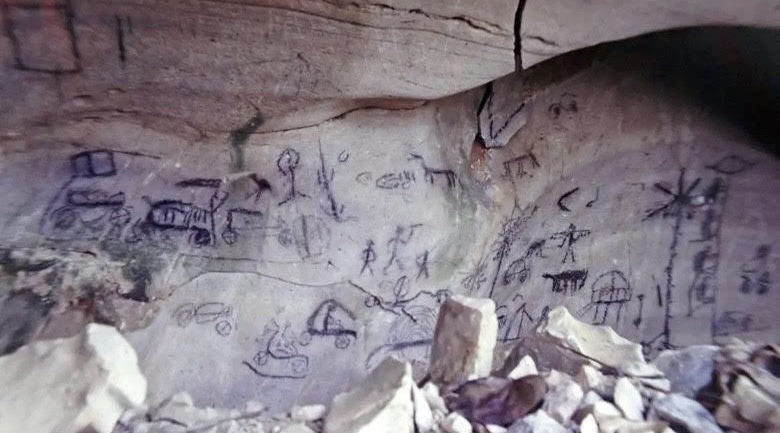

In addition to these prehistoric examples, some Malaysian rock art sites feature imagery from more recent periods. These include depictions of flags, human figures holding weapons, ships with sails, and individuals with hands on their hips. Such motifs reflect the dynamic and adaptive nature of rock art traditions, capturing moments of cultural contact, conflict, and transformation. Flags may symbolize colonial or national identity, while weapon-bearing figures evoke themes of resistance or dominance. Ships with sails highlight the region’s maritime connections, emphasizing trade, exploration, or migration. The assertive postures of figures with hands on their hips suggest changing social hierarchies or power dynamics.

Dr. Saw emphasizes the urgent need to preserve rock art in the face of environmental and human threats. Malaysia’s tropical climate, with its high humidity and heavy rainfall, accelerates pigment and rock surface degradation. Urban development, quarrying, unregulated tourism, and vandalism further jeopardize these fragile sites.

Photos of GUA BADAK, LENGGONG VALLEY – by courtesy of YEE CHUN WAH

Malaysia’s National Heritage Act provides a legal framework for protecting cultural sites, but enforcement remains inconsistent. Designating rock art sites as protected heritage zones can help shield them from development and exploitation. Enhanced surveillance, stricter penalties for vandalism, and public awareness campaigns can deter damage and promote respect for these cultural treasures.

Digital technologies, including high-resolution imaging, photogrammetry, and 3D scanning, offer invaluable tools for conservation. These methods create detailed records, enabling researchers to monitor changes, explore restoration options, and make rock art accessible through virtual archives.

Effective site management can mitigate environmental damage. Protective shelters, such as canopies or rain-diversion systems, can shield rock art from direct exposure to the elements. Controlling vegetation and water runoff around sites helps minimize erosion and biological growth. Additionally, barriers and designated viewing areas can prevent direct human contact with the artwork.

Indigenous communities, particularly the Orang Asli, are key to effective preservation. Their involvement in monitoring programs, workshops, and educational initiatives fosters a sense of ownership and pride, ensuring sustainable heritage management.

Tourism can be both a threat and an opportunity for rock art preservation. Sustainable tourism models prioritize heritage conservation while offering meaningful engagement for visitors. Visitor centers with digital replicas, guided tours, and interpretive signage provide alternative ways to experience rock art without compromising its physical integrity. Revenue from such initiatives can benefit local communities and fund conservation efforts.

Interdisciplinary collaborations between archaeologists, conservationists, and cultural organizations are vital. Innovative techniques, such as non-invasive graffiti removal, offer promising solutions. International partnerships can bring resources and expertise to address unique challenges in preserving rock art in tropical environments. Although Malaysia’s rock art heritage is in a fragile state, the advent of rapidly advancing technology and wider community involvement offers hope for their protection.

Shirley Abdullah

04 December 2024