By Christopher Higgs

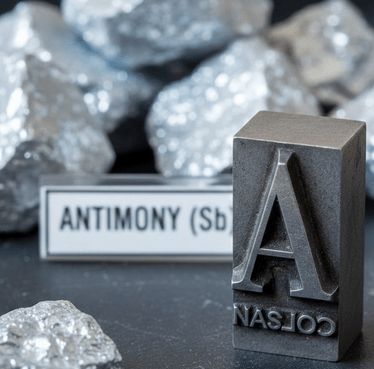

Sarawak’s evolution from a Bruneian province to a private kingdom was driven by the very mineral found in Gallery B’s brass celak container. This vessel held ithmid (kohl), a stibnite-based ointment used for cosmetic refinement and sun protection in accordance with prophetic tradition. However, this domestic mineral, antimony, soon became a global commodity. The resulting “antimony fever” provided the economic catalyst for James Brooke’s intervention, transforming a sacred substance of the Malay world into the industrial engine of a new colonial state.

The transformation began in earnest following the establishment of a British free port in Singapore in 1819, which provided the necessary entrepôt to connect Sarawak’s raw resources with global markets.

While the mineral had long been used for medicinal and aesthetic purposes, the Industrial Revolution found a vital application for antimony in the production of type metal for printing presses. Antimony is distinguished by a rare physical property: it expands as it cools from a liquid to a solid state. This expansion, when the mineral is alloyed with lead, ensures that the molten metal is forced into the finest details of a printing mould, producing sharp, durable type-faces. This physical oddity essentially provided the mechanical precision required for the mass production of the printed word, making Sarawak’s antimony a commodity of immense strategic value.

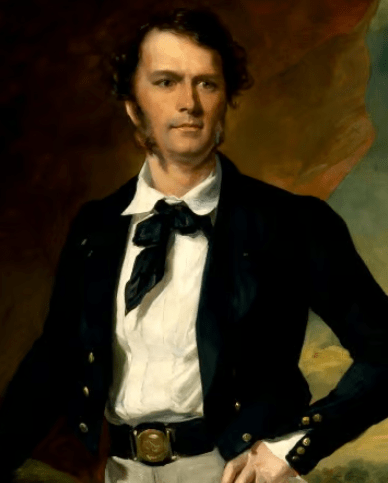

As the market value of the mineral soared in London during the 1820s and 30s, the Sultanate of Brunei sought to tighten its grip on Sarawak’s trade. The Sultan of Brunei sent Pengiran Indera Mahkota Mohammed Salleh to Sarawak, to establish a monopoly over the mineral. However, Mahkota’s reliance on forced labour and the heavy taxation of the local Malay aristocracy created a volatile atmosphere. By 1836, this pressure sparked an open rebellion led by the local elite, including Datu Patinggi Ali, against the Brunei central authority. The resulting stalemate left the territory crippled by civil unrest, a state of paralysis that persisted until the arrival of an English adventurer.

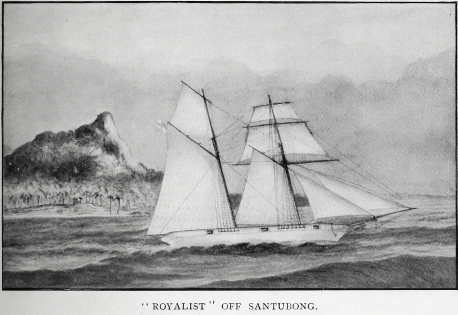

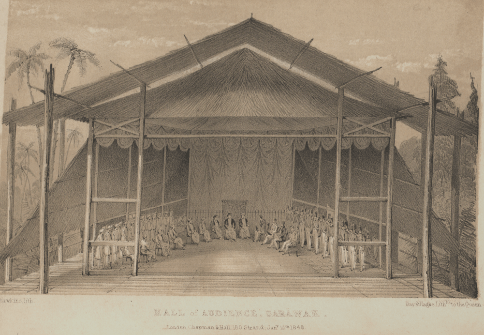

In 1840, during his second voyage to Borneo aboard the Royalist, James Brooke arrived to find the conflict he had first witnessed the year before, still unresolved. Pengiran Muda Hashim, the Bendahara of Brunei and uncle to the Sultan, formally requested Brooke’s military assistance to suppress the uprising in exchange for the governorship of Sarawak. Brooke’s intervention, which included bringing two of his 6-pounder cannons to the siege of the rebel fortifications, proved decisive, leading to the rebels’ surrender and exile in late December 1840.

To secure the cessation of hostilities, the families of the exiled rebel leaders were detained as hostages in Kuching under the supervision of the Brunei authorities. Despite the military resolution, Pengiran Mahkota obstructed the promised transfer of power for nearly a year. During this time the exiled rebel leaders allied with Brooke to resolve the impasse. On 23 September 1841, Brooke broke the deadlock by training the Royalist’s guns on Muda Hashim’s palace and landing armed men, forcing a capitulation.

The following day, Muda Hashim terminated Mahkota’s administration, transferring command of the government to James Brooke. This transfer was conditional upon an annual tribute: $1,000 each to the Sultan and Muda Hashim, followed by $300, $150, and $100 to the ex-rebel leaders, Datus Patinggi, Bandar, and Temenggong respectively. Known initially as the Tuan Besar, Brooke began his rule not as an independent king, but as the Governor of a provincial vassal of Brunei.

Brooke’s rule was a strategic extension of Muda Hashim’s dynastic ambitions. Displaced from the centre of power in Brunei by the rise of Pengiran Usop, the Bendahara sought to leverage Brooke’s military backing to rehabilitate his political stature. By suppressing the Sarawak rebellion and pacifying the recalcitrant Saribas and Skrang districts, which had long withheld tribute, Muda Hashim aimed to prove his indispensability to the Sultanate. Their partnership was a transactional bid for the throne.

The primary obstacle to Brooke’s expansion of power was the entrenched hegemony of the Arab Syarifs in the Sadong and Batang Lupar basins. These chieftains were descendants of the Prophet Muhammad who had settled in the region, leveraging their prestigious religious lineage to command significant political influence and local loyalty. By forging alliances with the Malay and Iban of the Skrang and Saribas rivers, the Syarifs maintained a traditional maritime economy dependent on raiding, a system Muda Hashim sought to dismantle in favour of a “non-piratical,” regulated trade network. To bridge the gap between this ambition and the reality of riverine resistance, Brooke secured the intervention of Captain Henry Keppel and HMS Dido. This introduction of Royal Navy firepower shifted the conflict from local skirmishes to systemic naval expeditions, targeting the Syarifs’ allies to clear the path for a centralised, commerce-driven administration under the Brooke-Muda Hashim alliance.

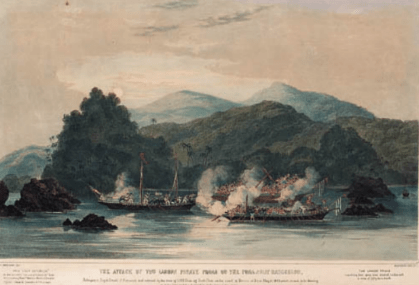

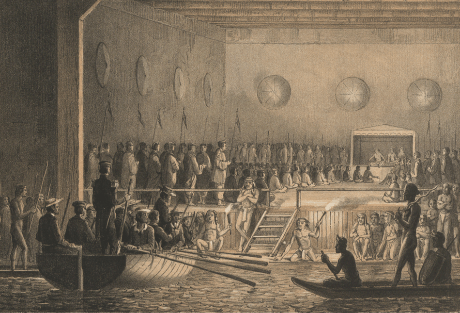

Lt. James Hunt’s lithograph depicts a 1843 skirmish off Tanjung Datu involving the Jolly Bachelor, James Brooke’s native-built boat. Borrowed by HMS Dido’s crew to intercept a mail ship, the vessel was ambushed by three Iranun prahus under cover of darkness. The attackers, expecting a vulnerable local craft, were overwhelmed by the disciplined firepower of British sailors. With two prahus destroyed and the third in retreat, the engagement served as a lethal introduction of the Royal Navy to the northwestern coast.

The 1843 Tanjung Datu skirmish introduced the contentious “Head Money” system to Borneo. Under the 1825 Piracy Act, British crews were incentivised with bounties of £20 per pirate killed and £5 per survivor. Captain Keppel’s testimony regarding the Jolly Bachelor incident—legally a tender to HMS Dido—confirmed twenty-three deaths from an estimated sixty-seven attackers. This single engagement earned the crew £795, a significant sum that later sparked outrage in London; critics argued such bounties encouraged the indiscriminate labelling of local maritime populations as “pirates” for financial gain.

Following the Tanjung Datu skirmish, the Brooke-Muda Hashim alliance attempted to negotiate with Syarif Sahib of the Sadong, whose support for Iban raiding parties continually destabilised Sarawak. The resulting summit at Pulau Burung proved largely fruitless, yielding only the symbolic promise of a future release of several Bidayuh captives. Recognising that Sahib’s power rested on his riverine allies, the coalition formed a plan to launch a series of punitive strikes against the Saribas and Skrang.

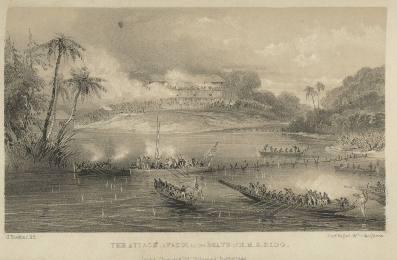

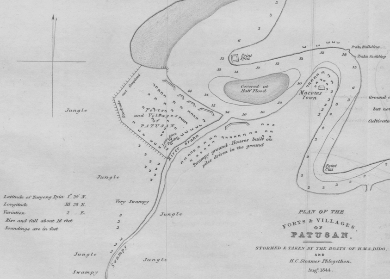

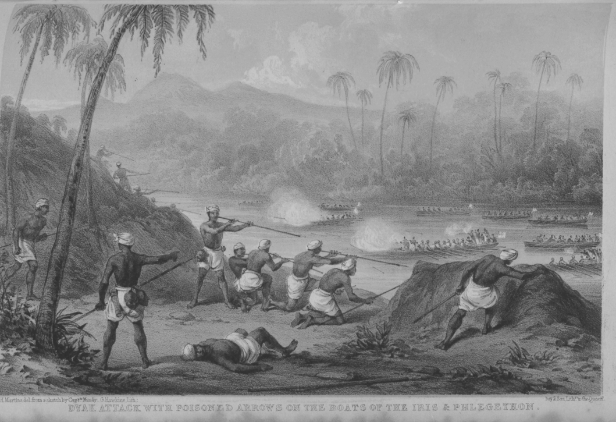

From the outset of hostilities in 1843, the Brooke-Muda Hashim military strategy relied on a massive disparity in manpower. While Captain Keppel provided a technical spearhead of roughly 80 to 100 Royal Navy sailors, the true weight of the coalition lay in a local levy of over 3,000 Malay and Iban warriors in approximately 300 native prahus. A small British minority providing rocket and shell fire, augmented by thousands of Sarawakian allies who conducted the primary riverine and land-based combat. Following a brief hiatus while Keppel was redeployed to China, this force resumed the offensive in 1844 with the added support of the HEIC steamer Phlegethon. After liquidating Syarif Sahib’s hegemony at Patusan, the coalition moved on to the Undop and the Skrang.

However, this overall victory was marred by a significant loss at the battle of Karangan Peris. There, the vanguard under Datu Patinggi Ali was lured into a devastating ambush; the Datu and 29 of his men were killed, demonstrating the high price paid by the Sarawakian majority that formed the backbone of Brooke’s expedition.

With the riverine systems brought into a tentative alignment with Brooke’s administration, the opportunity arose to restore Muda Hashim to the capital. In October 1844, Brooke facilitated this transfer through a direct application of gunboat diplomacy, taking advantage of Captain Keppel’s order for the HEIC Phlegethon and HMS Samarang to provide a formal military escort for Hashim’s family. This formidable naval presence provided the leverage necessary for the Sultan to re-instate Muda Hashim as Bendahara and recognize him as the heir to the throne. Yet, this forced consolidation of power proved tragic. Fearing the permanence of the British-backed faction, rival court elements convinced the Sultan that the Bendahara posed an imminent threat. In the violent purge of early 1846, Muda Hashim and most of his kin were killed, abruptly terminating the alliance and setting the stage for the British capture of Brunei later that year.

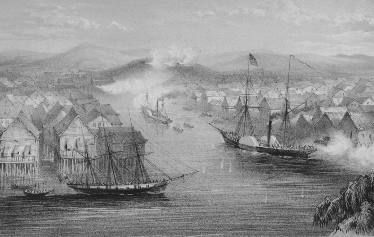

The massacre of his closest allies prompted a swift escalation by James Brooke, who appealed to Rear-Admiral Sir Thomas Cochrane for a decisive naval intervention. In July 1846, Cochrane led a fleet to force the capital.

The resistance was spearheaded by Haji Saman, a loyalist commander who instigated the conflict by firing upon the British ships as they ascended the Brunei River. Following a brief but intense bombardment, the British captured the capital, forcing the Sultan to flee into the interior. Haji Saman retreated to the Membakut River in modern-day Sabah.

This historical depiction of defenders using blowpipes illustrates the final stage of the 1846 conflict. While labels often misidentify these warriors as “Dayak,” they were specifically Dusun followers of Haji Saman. Following his flight from the fallen capital, Saman regrouped on the Membakut River, where the local Dusun population provided the primary defense against the pursuing British naval parties. In Bornean historiography, “Dayak” has frequently served as a colonial catch-all, but here it obscures the specific role of the Dusun as the true protagonists of the resistance on the Membakut.

Following the British seizure of Brunei in July 1846, Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin II was restored to the throne under conditions that fundamentally altered the status of Sarawak. By the terms of the new agreement, the annual tribute was abolished, effectively insulating Sarawak from further Bruneian interference. Although subsequent treaties continued to address James Brooke by the traditional honorific Tuan Besar, he now operated as an independent sovereign with the latitude to define his own status. Consequently, Brooke and his successors adopted the self-styled designation “Rajah of Sarawak,” a title that formalised their transition from provincial governors to the heads of an autonomous dynasty.

Photos

- Bekas Celak – © Christopher Higgs

- AI generated image of Antimony with typeface – prompted by Christopher Higgs

- Portrait of Mahkota – Public Domain – James Brooke 1846 – colourised by Christopher Higgs

- Portrait of James Brooke – Public Domain – Francis Grant, 1847

- Royalist off Santubong – Public Domain – Charles Roxburgh Wylie, 1909

- Hall of Audience – Public Domain – Henry Keppel, 1846

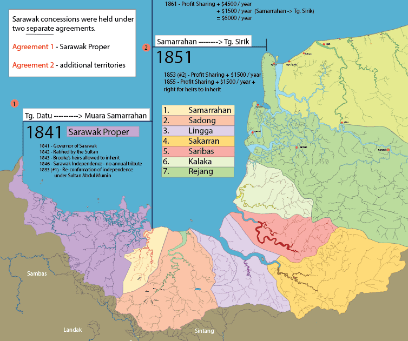

- Map of Bruneian Provinces East of Tg. Sirik – © Christopher Higgs

- The attack of two lanun prahus – Public Domain – James Hunt, 1846

- The attack on Paddi – Public Domain – Henry Keppel, 1846

- Plan of the Forts & Villages of Patusan – Public Domain – Henry Keppel, 1846

- Signing of the Treaty – Public Domain – Frank Marryat, 1848

- Capture of Brunei – Public Domain – Rodney Mundy, 1848

- Dyak Attack – Public Domain – Rodney Mundy, 1848

References

- Belcher, Edward (1848) Narrative of the Voyage of H.M.S. Samarang, During the Years 1843-46; Employed Surveying the Islands of the Eastern Archipelago; Accompanied by a Brief Vocabulary of the Principal Languages, 2 volumes, London: Reeve, Benham, and Reeve.

- Brooke, James (1846) ‘Letter to Henry Wise, 31 October 1844’, in Papers Relating to Borneo: Presented to Both Houses of Parliament by Command of Her Majesty, London: T.R. Harrison, p. 49.

- Brooke, James (1853) The Private Letters of Sir James Brooke, K.C.B., Rajah of Sarawak, Narrating the Events of His Life, from 1838 to the Present Time, edited by John C. Templer, 3 volumes, London: Richard Bentley.

- Brooke, James (1862) ‘Letter to Henry U. Addington, 13 March’, Foreign Office 12: Borneo (Diplomatic and Consular Reports), Vol. 11, Kew: The National Archives.

- Crawfurd, John (1828) Journal of an Embassy from the Governor-General of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China; Exhibiting a View of the Actual State of those Kingdoms, London: Henry Colburn.

- Gould, S. Baring-Gould & Bampfylde, C. A. (1909) A History of Sarawak Under Its Two White Rajahs 1839-1908, London: Henry Sotheran & Co.

- ‘In Preparation, in 2 vols. 8vo. The Expedition to Borneo of HMS Dido’ (1845) The Morning Post, 9 May, pp. 8.

- Jacob, Gertrude L. (1876) The Raja of Saráwak: An Account of Sir James Brooke, K.C.B., LL.D., Given Chiefly Through Letters and Journals, 2 volumes, London: Macmillan and Co.

- Keppel, Henry (1845) ‘Report on the Operations against the Pirates of Borneo’, The United Service Magazine, Part III, pp. 112-125.

- Keppel, Henry (1846) The Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the Suppression of Piracy: With Extracts from the Journal of James Brooke, Esq. of Sarāwak, 2 volumes, London: Chapman and Hall.

- Marryat, Frank S. (1848) Borneo and the Indian Archipelago with Drawings of Costume and Scenery, London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans.

- Mundy, Rodney (1848) Narrative of Events in Borneo and Celebes, down to the Occupation of Labuan: From the Journals of James Brooke, Esq. Rajah of Sarāwak, and Governor of Labuan. Together with a Narrative of the Operations of H.M.S. Iris, 2 volumes, London: John Murray.

- Pringle, Robert (1970) Rajahs and Rebels: The Ibans of Sarawak under Brooke Rule, 1841-1941, London: Macmillan.

- Runciman, Steven (1960) The White Rajahs: A History of Sarawak from 1841 to 1946, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rutter, Owen (1930) Rajahs Brooke & Baroness Burdett Coutts: Consisting of the Letters from Sir James Brooke, first Baronet and Rajah of Sarawak, to Miss Angela (afterwards Baroness) Burdett Coutts, London: Hutchinson & Co.

- Sanib Said (1985) Malay Politics in Sarawak, 1946-1966: The Search for Unity and Independence, Singapore: Oxford University Press.

- Sanib Said (2024) The Historical Significance of September 24: From Brunei Province to Sarawak Kingdom, Public Talk at Pustaka Negeri Sarawak (Kuching), 24 September.

- Savage, James (1845) ‘Letter to Henry Wise, 16 November’, Foreign Office 12: Borneo (Domestic Various), Vol. 12 [1852], Kew: The National Archives.

- St. John, Spenser (1855) ‘Letter to Lord Clarendon, 25 October: Minutes of a conversation between the Datu Bandar, the Datu Imaum, the Datu Tumangong & the Tuan Khatib, Members of Council of State of Sarawak’, Foreign Office 12: Borneo (Diplomatic and Consular Reports), Kew: The National Archives.

- Tarling, Nicholas (1955) ‘British Policy in the Malay Peninsula and Archipelago, 1824-1871’, Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 28(3), pp. 1-228.

- Tarling, Nicholas (1982) The Burthen, the Risk, and the Glory: A Biography of Sir James Brooke, Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

- Walker, John Henry (2002a) Power and Prowess: The Origins of Brooke Kingship in Sarawak, Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

- Walker, John Henry (2002b) ‘The Power of the Word: The Interaction of Literacy and Orality in the Royal Navy’s Suppression of Piracy in Sarawak’, Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 75(2), pp. 45-56.