by Annie Chuah Siew Yen

What’s a name?

A name may be just a term used for identification of a person, object or place, but studies have questioned the psychological effect names have on the bearer. To some, a rose by any other name would smell as sweet, while to others a name defines a place or person’s life. So vital is the significance of a name that many communities have traditions surrounding its selection.

There must be a reason why there are at least three different places in Indonesia named Gunung Kawi (Mount Kawi). It may be an eponym for ‘Kawi’, the ancient sacred language of Java, which existed in the 8th century CE, and still used to some extent as a literary language. The word, in Sanskrit-derived forms can mean ‘poetry, wisdom or sculpture’, leading to the surmise that it may mean ‘Mountain of Wisdom/Poets’ or ‘carved out of mountain’.

Gunung Kawi, East Java

My first encounter with Gunung Kawi was when I was on a round island tour of Java in 1991. My co-travellers were mainly Indonesian Chinese from different parts of Java and as far as Medan in north Sumatra, who had joined the tour because Gunung Kawi was on the itinerary. They related (to me) the hagiasmos or sanctification ritual of this mist-shrouded mountain, which is the resting place of two of Indonesia’s legendary figures.

Gunung Kawi, located in the administrative area of Wonosari Village in the Malang Regency of East Java, is a stratovolcano with no eruption in recorded history. It gained fame because of matters relating to pesugihan often held there. Many do so because of the quest for infinite wealth. Pesugihan is derived from the Javanese word ‘sugih’ meaning ‘rich’. It is a ritual performed as a means to get rich instantly. In exchange, the seekers must sacrifice something.

At 2500 metres above sea level on the slope of Gunung Kawi is Pesarean Gunung Kawi – a cemetery containing the sacred twin tombs of Mbah Djoego and Iman Soedjono, revered historical figures in Indonesia. Iman Soedjono was one of the seventy noblemen who took arms against the Dutch occupation led by Prince Diponegoro from 1825 to 1830. Next to his grave is the tomb of Mbah Djoego or Kiai Zakaria II, a local figure who pioneered a new technology in farming at that time. He was a brave fighter and spiritual adviser to Diponegoro. Both were descendants of the kingdom of Mataram, loyal to Pangeran Diponegoro. Though the tombs are of Muslim deceased, this place has a magical appeal to Chinese, Madurese and indigenous communities of Indonesia who are in search of spiritual blessings.

These ancient urns beside the left tomb belonged to Djoego and have been used for the storage of holy water for healing. It is believed that drinking water from this urn will keep people young. Image credit: http://gunungkawi.files.wordpress.com/2009/04/guci-kuno.jpg?

The cemetery is located at the top of the village and along the way are several gates with reliefs that tell the story of how Mbah Djoego fought the war with Prince Diponegoro. The reliefs were carved by his followers in 1871 to commemorate his heroic deeds. Near the cemetery is the holy sian tho (sacred fruit) tree, also known as the dewandaru tree, believed to have sprung from Djoego’s stick, which was stuck to the ground for protection of the Wonosari area. Pilgrims wait around the tree for the fruit, leaves or even twigs to fall to be kept as a wealth-giving talisman.

Adjacent to the tomb house is a mosque. Within the pesarean complex is also a Confucian/Buddhist temple with Kwan Im as the main lord. In years past, some people from the local Chinese community who conducted the rituals here were believed to have become fabulously rich or healed from their sickness after the rituals. News spread, and more Chinese resettled at Mount Kawi. In time, the village became known to other Chinese communities and the Buddhist temple was built near the pesarean.

Some distance away is a building, once the hermitage belonging to Prabu Kameswara, a prince from the Kingdom of Kediri who was Hindu. He was a deeply religious person who preferred to live in meditative seclusion. It was said that after the prabu finished meditating in that place, he succeeded in resolving the political turmoil in his kingdom. This is now a place for worship and the practice of pesugihan.

On this mountain refuge, the sanctuaries of three different faiths exist harmoniously side-by-side, which is not unusual among Indonesians. Though this is a good place for photography, its uniqueness as well has attracted many to Gunung Kawi; they come not only for a vacation but also, for believers of animism, this is a pilgrimage site. Visitors believe that the pilgrimage will bring them success in their careers, good health and prosperity. The best time to visit the sacred sepulchres is on Thursday evening, Jumaat Legi according to the Javanese Calendar. Gunung Kawi is one of the most popular pilgrimage destinations for Indonesian Chinese, with the Jumat Legi before the Lunar New Year being especially busy.

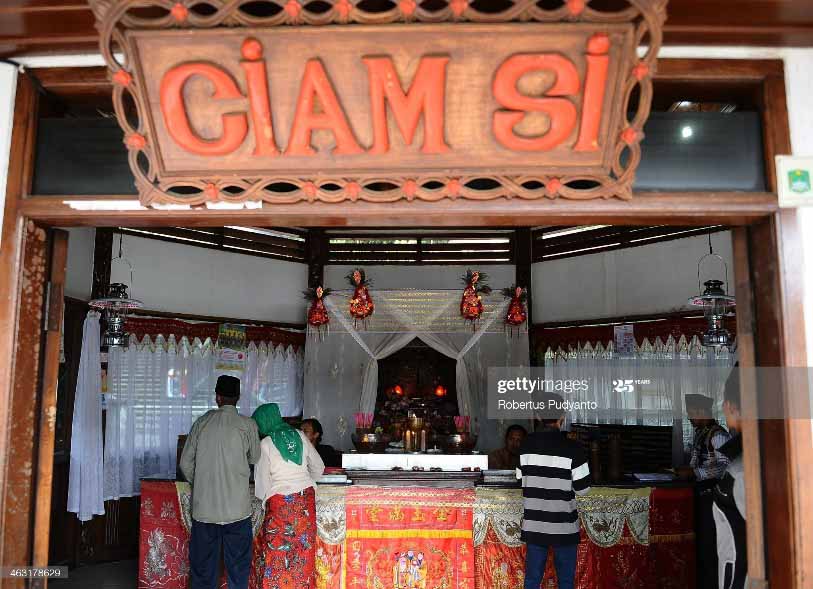

The smell of incense pervades the air; patrons come to have their fortunes revealed through the ancient Confucian/Taoist ritual known as kau ciam si (roughly translated from the Hokkien dialect to mean ‘seek/consult bamboo oracle’), a method of fortune revealing. It involves shaking a cylindrical container filled with oracle sticks made of bamboo, numbered 1 – 100, in such a manner that an oracle stick will mysteriously jump out. The number on the stick will be matched with the interpretation of the oracle on the divination slip of the same number, and therein lays the fortune you seek. The divination message may be an aphorism, epigram or proverb; it is cryptic and enigmatic. It is usually deciphered by a temple staff, its accuracy dependent on the knowledge of the interpreter. The practice of kau ciam si dates back to the Jin Dynasty, and is still prevalent in Taoist temples in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Thailand, Singapore and Malaysia.

In recent years, Mount Kawi not only functions as a sacred space (the pesarean) for pilgrims and visitors, but it also has a ‘profane space’ for other visitors who come to enjoy the natural beauty and the cultural and inter-faith performances of the region. These are initiatives of the government of Malang Regency in its attempt to change the image of Gunung Kawi and erase the stigma of Mount Kawi as a Pesarean.

Pura Gunung Kawi, Bali

Down in a valley through which runs a stream near Tampaksiring in Ubud, Bali, is an interesting archaeological complex – an antiquated sanctuary of edifices – Pura Gunung Kawi.

Unlike other temples in Bali, this mist and mystery-shrouded one is rather laid-back with few foreign visitors, but was on former President Obama’s itinerary when he and his family holidayed in Bali in 2017. I visited in August 2019 on the suggestion of the manager of the Ubud resort where I was spending a week. The complex radiates a certain mystique; legends of long-forgotten gods, kings and heroes have been told about its origin. But then, isn’t Bali a land of legends?

As you make your way down to the temple, a descent of 270 steps, you are met with beautiful vistas of luxuriant paddy fields, and finally welcomed by the sound of running water. Where the stairs end, there is an archway with pillars holding basins of holy water, which visitors sprinkle to cleanse themselves before entering the complex.

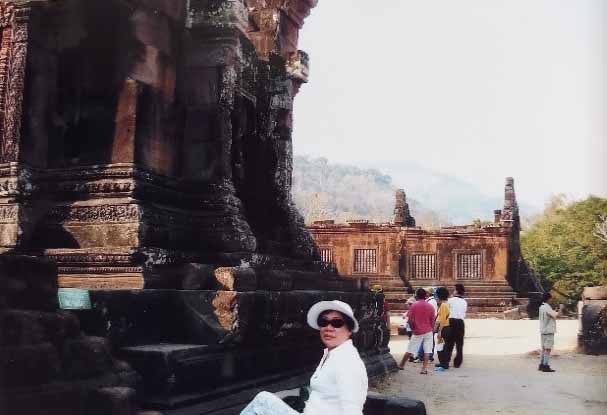

Pura Gunung Kawi’s setting among rice terraces and natural jungle makes its location quite stunning. The ancient artwork carved onto the cliff are of four candi or shrines on the west side and another five on the eastern side of the river, while another is hidden to the south across the valley. Evidence suggests that these candi were probably once protected between two massive rock-hewn cloisters. Each candi is believed to be a memorial to a member of the 11th-century Balinese royalty, but little is known of this. Legends relate that the whole group of memorials was carved out of the rock face in a single night by the mighty fingernails of the mythical giant Kebo Iwo.

The five candi on the eastern side are dedicated to King Udaya, Queen Mahendradatta and their sons Airlangga, Anak Wangsu and Marakata. When Anak Wangsu was ruler of Bali, Airlangga ruled eastern Java and became the legendary king of Singhasari (Singosari). The other four are for Anak Wangsu’s chief concubines and the remote tenth candi is for a royal minister. Another theory states that the whole complex is dedicated to Anak Wangsu, his wives and concubines, and a royal minister.

As the temple is held sacred, proper attire consisting of a sarong tied around the waist is required for all visitors. Image credit: Annie Chuah

These candi (niches) are not tombs and they have never contained any human remains, but their function has not been ascertained. Their shape resembles small buildings with three-tiered roofs bearing nine stylised lingam-yoni symbols. The doorway seems to be going nowhere. There is a small chamber beneath each candi for offerings of food and metal objects representing earthly necessities.

Within the complex are small stone caves and cells hewn out of rock that serve as meditation sites to complement shrines where Buddhist monks used to sit and contemplate. In Bali, Hinduism and Buddhism have coexisted and fused in harmony since ancient times. As you wander between monuments, shrines, fountains and streams, there is a feeling of ancient majesty.

Gunung Kawi Sebatu, Bali

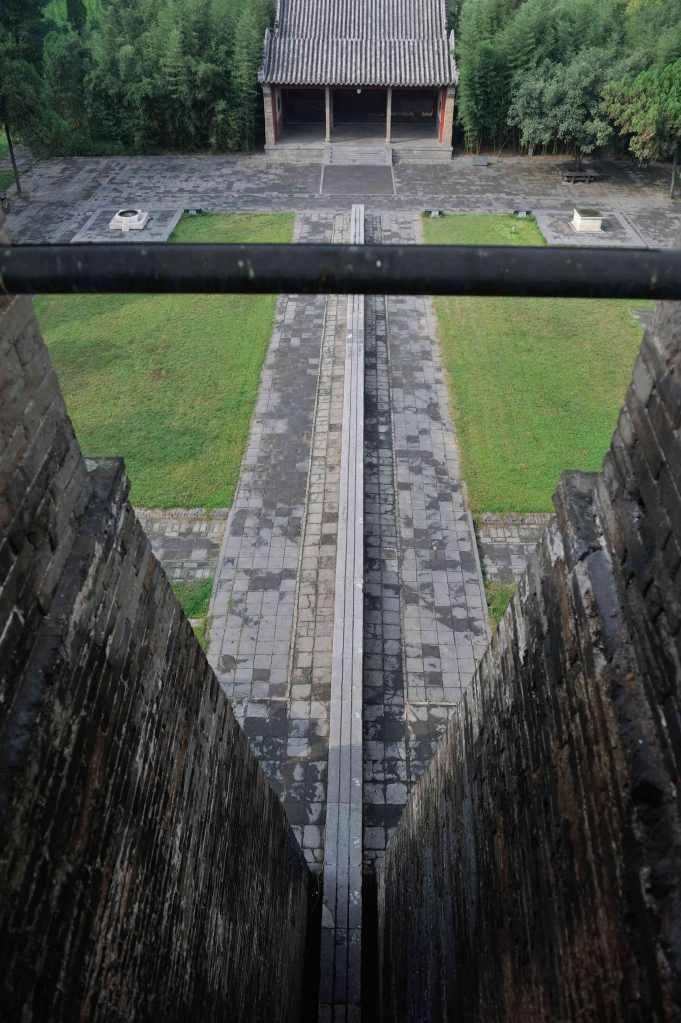

About 10km away in Gianyar, is another sacred temple – Gunung Kawi Sebatu, a Hindu water temple dedicated to Vishnu. This 11th century temple complex, built on a natural spring, comprises a collection of ancient shrines, bathing pools and fountains. The architectural interest is in its split gates, richly carved walls and the variety of shrines and pavilions.

Entry into the main temple is reserved for Hindu devotees but other pavilions and shrines for ancestral spirits can be explored. Artisans in the mountain village of Sebatu were skilled wood carvers and sculptors. Carved beams and depictions of deities and demons in stone can be seen throughout the temple.

There is a shrine dedicated to the Javanese sage Mpu Kuturan, a priest instrumental in the establishment of Balinese Hinduism. To the right of the central court is the temple of the Pasek Gelgel clan where the ancestral deities are honoured in nine shrines.

The reflecting pool with a floating pavilion is in the outer courtyard; further beyond is the performance pavilion. Some pools are for purification ritual baths while shoals of carps are reared in others. Fowls roam around the jungle setting. The Gunung Kawi Sebatu temple is a gem, one of the prettiest temples in Bali, so visit before the crowds come to know about it!

Elaborate ceremonies are held to celebrate the temple anniversary, Purnama Sasih Kasa, on the first full moon of the Balinese calendar and attended by Balinese Hindu pilgrims from all over the island.

The Balinese are expected to participate in the temple anniversaries of their clan temples to reinforce their clan identities. This is the time their ancestors come down for visits to be welcomed with dance and food.

Throughout the world people look up to mountains as sources of blessings and healing, as in these spiritual Gunung Kawi sites in Java and Bali. Sacred mountains incite reverence and are the subject of legends. Spirituality provides a sense of peace and helps us understand why these Gunung Kawi remote locations are held in such mystical regard by the natives of the land.

References

https://jatimplus.id/gunung-kawi-kisah-tentang-pelarian-dan-harapan/

Culture Tourism to Pesarean Kawi Mountain as A Culture of Cultural Products

http://pesugihangunugkawi.blogspot.com/p/blog-page.html

https://trip101.com/article/witness-the-culture-and-religious-harmony-at-mount-kawi-malang-indonesia

http://www.baligoldentour.com/gunung-kawi-temple.php