Speaker : Dato’ Kapten Professor Emeritus Dr Hashim Bin Yaacob

Write-up by Shirley Abdullah

In Malaysia and the Malay-speaking parts of Southern Thailand, Wayang Kulit may be classified into four categories;-

Wayang Kulit Siam (Wayang Kulit Kelantan)

Wayang Kulit Jawa (Wayang Kulit Melayu)

Wayang Gedek (Nang Talung)

Wayang Kulit Jawa (Wayang Purwa)

Prof Dr Hashim focused his talk on his personal experience as a practitioner of Wayang Kulit Siam . He also performed selections from repertoires written by himself, with the assistance of his colleague, Che Su. MV Anne was also roped in to perform as one of the characters and mustered a convincing turn as the evil protagonist ! We could see that the performance involves a great deal of arduous effort and the tok dalang has to be highly skilled in order to accomplish a seamless performance.

Commenting on the evolution of various forms of wayang kulit in Kelantan, he said that in the 1920’s, puppeteers from Kelantan were sent by the royal court to Java to learn the Javanese form of shadow play, primarily for performances within the confines of the royal households. However the stiff, archaic, classical styles generated little enthusiasm among viewers. “There was little movement, they kept repeating the same themes in the storylines, it was boring, thus it died a natural death, “ he said.

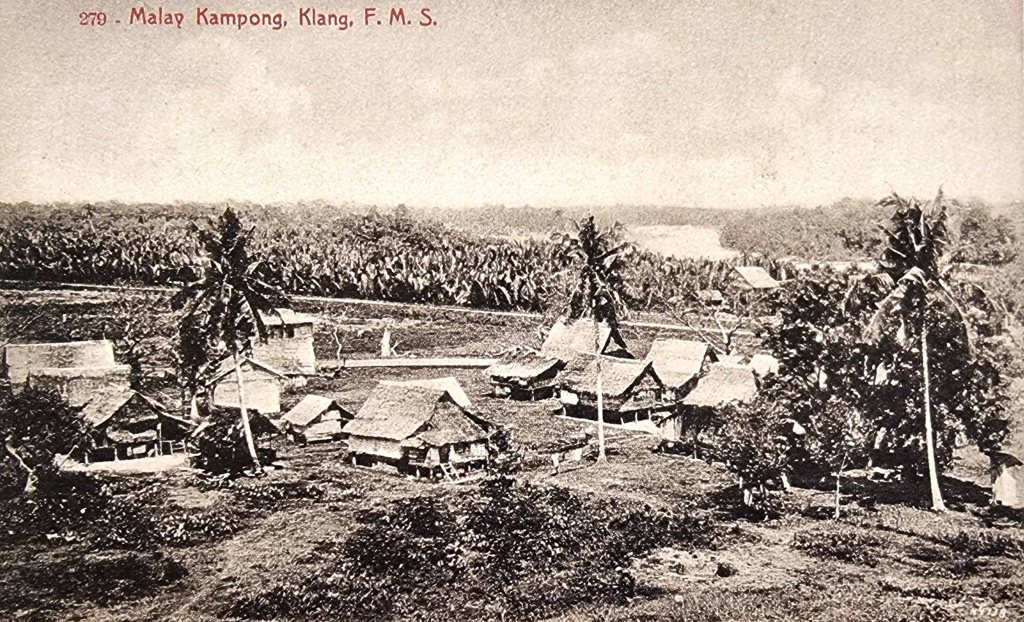

Wayang Kulit Siam is still performed in Kelantan, Terengganu, Kedah, Perak and Patani. In the past, it was much cherished as a source of entertainment by village folks.. Often the performance is completed in a single night but Prof Dr Hashim recalls occasions, usually connected with wedding celebrations when the performances were extended over seven nights, and generated considerable excitement among enthralled rural audiences.

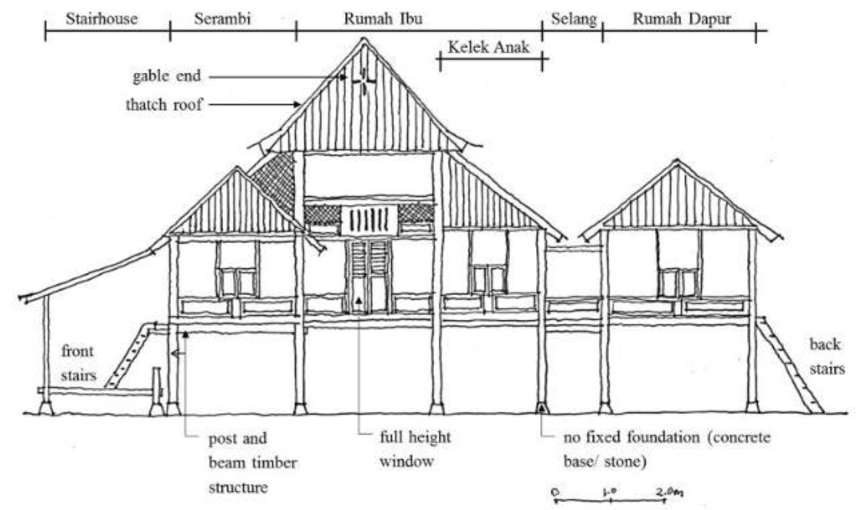

The wayang kulit performances take place on an open-air theatre (panggung) elevated about one metre above the ground. Spectators will be seated in front on the grass or on benches .

The panggung represents the universe. The screen at the front of the stage , on which shadows of the puppets are projected, represents the world with images of people passing through. The dalang gives life to the puppets by switching the lamp (symbolizing the sun) , on and off

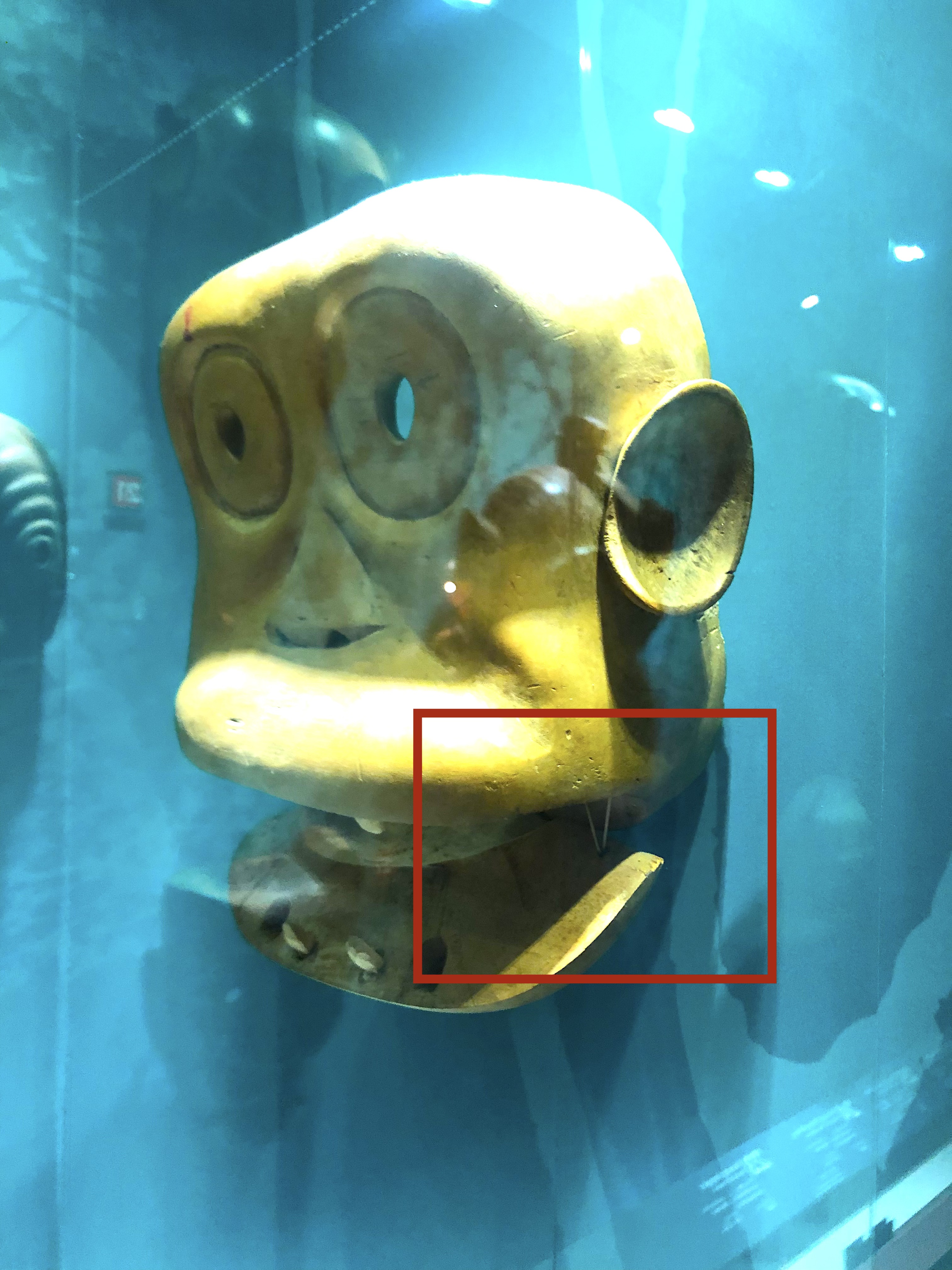

The tree of life ( Pohon Beringin ) represents the elements ( water, earth, air, fire.)

The Tok Dalang ( dalang ) narrates the story and mimics the voices of the various characters. To do this, he has to sing as well as modulate his voice for dozens of parts The puppets have a sharp split-bamboo point on their base which is stuck onto a banana stem. This enables the dalang to deftly switch puppets for different characters.

Apart from being skilled in puppet manipulation, the dalang coordinates his performance with the orchestra who receive cues from him.

The orchestra comprises of between seven to ten musicians, who play a double-reed oboe ( serunai ), gongs ( tetawak, canang), hand cymbals ( kesi ), and various drums ( gendang, gedumbak, gedung ).

The principal Wayang Kulit Siam storyline is based on Hikayat Maharaja Wana, a Malay version of the Ramayana. The original trunk story ( cerita pokok ) focuses on the rivalry between Rama and Ravana for Siti Devi’s hand.

Branch stories (cerita ranting) were spin – offs invented by dalangs who used characters from the Ramayana but developed new story lines. This afforded them the opportunity to also highlight contemporary issues, and provide social commentary. Entertainment for the masses remained the main focus so performances were heavily laced with humour and rousing music .

According to Prof Dr.Hashim, he is concerned that Wayang Kulit in its current state as an art form is fast approaching the point of extinction.

He is aware that not many people are interested in viewing wayang kulit performances, not to mention actively promoting it. This is also because not many are able to understand the language used during the performances. This is predominantly the Kelantanese dialect of the Malay language, which is challenging for even native Malay speakers from out of state.

He also felt that wayang kulit performances failed to attract a younger audience because they did not incorporate contemporary elements. Neither the traditional storylines nor the music had evolved or adapted to satisfy the appetites of the younger generation.

The banning of wayang kulit performances by the state government of Kelantan in 1998 had also dealt a serious blow to the art form. The negative perception created by the labeling of wayang kulit performance as haram and going against the teachings of Islam had a considerable impact especially in deterring the older generation from patronizing the art form. The ban has since been lifted in 2019.

Prof Dr. Hashim explained the reason for the initial ban on Wayang Kulit Siam performances.

Wayang kulit is performed by a master puppeteer known as “Tok Dalang”. The tok dalangs were also bomohs who served the local communities as Malay shamans and traditional medicine practitioners. They were steeped in traditions and rituals in which they claimed to act as intermediaries for spirits.

The Tok Dalangs performed rituals in conjunction with Wayang Kulit performances such as “Kenduri” (feast), “Buka Panggung” (rites to commence the theatre ) and “Berjamu” (ritual performance). These rituals involved the recital of invocations for appeasement of the spirits which constitutes “syirik” (associating others with God). During the performances, the dalang could also go into a trance. Ascribing power to anything other than the one God violates Islamic belief (monotheism).

While Prof Dr. Hashim was a dentistry professor at Universiti Malaya, he was already heavily involved in the Malay poetry scene. He ventured into performing poetry recitals in public in an attempt to curb a nervous condition when he first became a young lecturer. He strongly advocates public performance to anyone who wants to conquer stage fright ! Since then he flourished as a prolific poet with five anthologies of poetry publications and the prestigious Anugerah Sastera Perdana ( National Literary Award ) under his belt.

His close friendship with the then Vice-Chancellor of Universiti Malaya Royal Professor Dr. Ungku Abdul Aziz Ungku Abdul Hamid also influenced his interest in culture and arts, as both shared a mutual interest in fostering and promoting local art forms.

The Kelantan state government ban on wayang kulit in 1999 aroused his concern for the future of the art form. Prof Dr. Hashim draws from a family lineage of wayang kulit dalangs; his grandfather Jusoh was a revered dalang.

After being schooled for 7 years by renowned Kelantanese dalang, Dollah Baju Merah and his pupil Ariffin Che Mat, he ventured into live performances as a dalang in rural Kelantan. Instead of the traditional incantations to the spirits which accompanied traditional performances, he recites Islamic prayers during the opening and closing of the show. His intention is not to transform wayang kulit into Islamic wayang kulit but to make it compatible with government rulings as well as to popularize it and enable the art form to thrive.

Prof Dr.Hashim made efforts to remove elements which are in conflict with Islamic teachings from the performance scripts. He has invested considerable time and effort to propagate a better understanding and appreciation of Wayang Kulit by writing books which provide translations of the language used in the performances and explanations of the story lines. To make wayang kulit more accessible to the man on the street, he uses standard Malay during his performances. He has also performed Wayang Kulit as a puppeteer not only in Malaysia but also in Singapore, Egypt, Indonesia ,India, Japan, and Korea He has also delivered his performances in various languages such as in Mandarin, English and Arabic.

While purists lament the decline of the art form in its original state, Prof Dr.Hashim stresses that adhering to the traditional style will only result in declining audience numbers. He feels that wayang kulit plots should go beyond the traditional plots from the Ramayana. He has written scripts with unorthodox themes and many of them are humorous skits. When he was Vice-Chancellor of Universiti Malaya in 2003, he taught wayang kulit as a 28- hour elective.for undergraduate students.

How did the practitioners of Wayang Kulit Siam and their audience, who were mainly Muslims, receive Hindu influenced storylines?

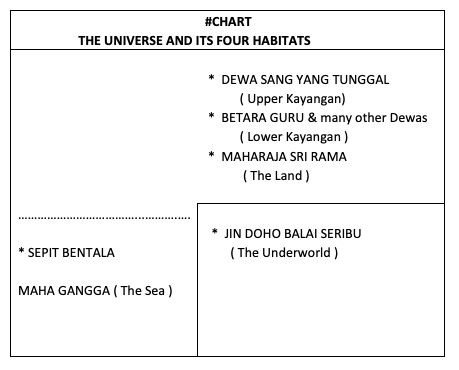

In his book, Prof Hashim explained that according to Dollah Baju Merah, the renowned master puppeteer , the Universe is divided into four habitats with their own inhabitants.

Refer to the chart below :

CHART : THE UNIVERSE AND ITS FOUR HABITATS

OF WAYANG KULIT SIAM ( WAYANG KULIT KELANTAN )

# Reference: Sejarah Dan Pengalaman Gaya Bahasa Wayang Kulit; Author : Hashim Bin Yaacob Publisher: Pekan Ilmu Publications Sdn Bhd

The chief of the universe resides in the uppermost kayangan and he is known as Dewa Sang Yang Tunggal. The term “Tunggal” means “one” which denotes the oneness of the Dewa, creator of the universe of the wayang kulit, who has great power over all things.

The ocean in Wayang Kulit Siam is ruled by a dragon – king called Sepit Bentala Maha Gangga, the underworld by a genie (Jin) called Jin Doho Balai Seribu and the land by a mortal , Sri Rama.

“Sri Rama, the hero prince of Wayang Kulit Siam epitomizes the perfect man, at the very least in the physical form. What then are some of his attributes to warrant the privilege ? Whatever they are, they must be conjured up according to the taste of the day among the Wayang Kulit Siam supporters”, said Prof Dr.Hashim.

We are told that out of boredom and loneliness in the Uppermost Kayangan , Dewa Sang Yang Tunggal decided to descend to earth to see the affairs of the world, disguised as a commoner.

His willingness to suffer humility and become the servant of Maharaja Wana is viewed as a positive trait. The practice in humility ( rendah diri ) and modesty is a distinctive feature of the social conduct in Malay society which persists until today.

Clear messages can be drawn from the varied dramatic repertoires, which may influence the general audience in leading their lives, in their code of conduct and in their perception of the world. Negative traits among humans such as ungratefulness, pride, greed, telling lies, slandering a person, ridiculing a person are also emphasized as undesirable traits.

The importance of forging close ties among family members is also expounded. Sri Rama could always count on the help of his younger brother, Raja Muda Laksamana, and his son, Hanuman Kera Putih..

Prof Hashim feels that one of the most important messages is the respect accorded to learned individuals ( orang yang berilmu ) and the process of acquisition of knowledge ( ilmu ) itself. Wayang Kulit Islam also emphasizes relationships between men and women through marriages. In its repertoires, we are constantly reminded of the love Sri Rama had for his wife, Siti Dewi . Sri Rama had to face all odds and obstacles including fights against the demon king, Maharaja Wana, in order to win back his wife after she was abducted.

Prof. Dr.Hashim feels that the positive messages in Wayang Kulit Siam are a reflection of the teachings in Islam and are imparted by dalangs through the heroes and villains of the various repertoires. He remains positive about the future of this treasured art form . He emphasizes that even though it is necessary for the art form to evolve to ensure its survival, whatever efforts taken must ensure that the local identity of the people of the land should not be lost.