Danie Picot

When navigating up the Klang river to try and go as far upstream as possible, you have to stop at this confluence between two rivers. The current becomes more tumultuous as you approach the mountains. The passengers of the boats have already suffered three long days to go upstream, they have to move forward with a long stick planted in the river bed, they take the pole in turn. During this river trip, they stop at the Damansara river, there is a “pengkalan”, a wharf where one can moor the long boats loaded with food and equipment. There, travelers can find enough food to refresh, a lot of fruits, spring water, raised platforms to rest and prepare for the long ascent.

When they see the foothills looming, when the pole can no longer fight against the flow, they stop at this second “Pengkalan” in the heart of the jungle.

There are a few houses on stilts, they belong to the Temuan who are settled Orang Asli.

On a hill a little further live the Mandaling people who came from Sumatra in the middle of the 19th century.

The place has no name.

Klang River, circa 1880. (Source: KITLV Universiteit Leiden)

It is a confluence and a landing place that is called Pengkalan in Malay and Temuan. Over time, towards the end of the 19th century, more and more people arrived and settled, they spoke different languages, the word “pengkalan” changed, got misspelled, became “kalan” and then “kuala”.

Yet a “kuala” is an estuary, not a confluence, but it is kuala that remains.

There are other Kuala that are not estuaries, Kuala Kangsar, royal city on the Perak river,

From Pengkalan Lumpor, this village between two rivers was now called Kuala Lumpur. The boats arrived, docked, and left. Coolies, men, women and children trampled on the water edge, they lived there, it became muddy, the water rose quickly during the rains, the place was certainly muddy.

The river was brown, silty. For a long time, the veins of tin ore upstream had been worked, the mines size increased and more alluviums went down the current, muddying further the water.

In bahasa Melayu, mud is Lumpor, which became Lumpur.From Pengkalan Lumpor, the muddy wharf, this village between the two rivers was now called Kuala Lumpur.

Lumpur is sometimes explained differently. Several maps and testimonies speak of the Lumpoor River. Anderson was a translator and writer of the English East India Company, he crossed the Klang river in 1818. He wrote ”the river is easily navigable up to the confluence with the Damansara river. Then it goes further up to the tributary Sungei Lumpoor, where we can mine the tin deposits.”

A Chief Mines Inspector, Gripper, wrote that the Sungai Lumpur merges with the Klang River. To Gripper, the Gombak river was the Lumpur river; it changed its name after the Selangor Wars 1873. According to Malaysian custom, the confluence takes the name of the smaller of the two rivers, Kuala, the wharf, took the name of Lumpur.

Today in Kuala Lumpur the muddy estuary is a confluence where 2 rivers meet, the Gombak and the Klang, the water is rather green-brown but not really muddy, the fish jump there lightly, sometimes between plastic bottles going down the stream. Thanks to the government rehabilitation program called River of Life, the Klang and the Gombak are getting a makeover, to the delight of walkers and visitors.

source : https://www.malaysia-traveller.com/old-malaya-photos.html

The banks had been inhabited for a long time. The Temuans, natives of the region settled there. They live in houses on stilts. The river was meant for fishing, ablutions, wandering buffaloes, as a playground for children, and a thousand daily chores.

Thanks to the numerous streams which cross the jungle, people cleared and planted rice fields, enough for the community and a little more for trade. They used to cruise down with their canoes to the mouth at Pengkalan Kallang (Klang). They needed salt, cotton, knives, metal hooks and baked clay ovens. They enjoyed ikan bilis, sun-dried fry that improved their staple food. They brought rice, durians and wild rambutans. Medicinal herbs were much sought after because the Temuan Shamans knew how to cure fevers, blood clots, kidney disease, and much more thanks to herbs and animals. Also, in baskets braided with pandan leaves, they brought tin ore.

The Temuans exploited the rich deposits of the Klang and Gombak rivers and their smaller tributaries: Sungai Ampang, Sungai Sering, Sungai Bunus, Busuk, Kerok, Jinjang, Kemunsing, Belongkong, Puteh. They worked like gold panners do: using large wooden trays they rotated, the water discharged and the ore remained at the bottom of the tray. Villages of few houses were scattered along rivers and in the jungle. There was a network of trails through the forest. When they went up with their goods against the current, they stopped at a larger confluence where the Damansara river joined the Klang. Then they went further upstream. It is quite possible that they had already opened a path through the jungle between the confluence of the Damansara and the next confluence between the Klang and the Lumpoor. Attack by a tiger on this road was not uncommon. Today the tigers are driving their car along that same jalan Damansara.

This is how Kuala Lumpur became a gateway to an interior rich in tin and forest products. Thanks to the pathways along the rivers and streams, one can cross the cordillera and reach Pahang and its rich gold mines.

Other people went up the river: men, women, families in small groups, settled at the confluence. The Sumatran Mandallings cleared a hill on the left bank of the Klang, out of reach of flooding and planted pineapples. It’s Bukit Nanas.

The Mandallings were refugees fleeing from wars called the Padri War and Dutch colonization.

[The Padri were a group of Muslims influenced by the Wahhabis during a trip to Mecca. At the beginning of the 19th century the Padri sought to purge the culture, traditions and beliefs of the people of Sumatra such as the Minangkabau, the Mandallings, the Rawas, the Raos because they believed that their customs were not in accordance with Islam. Smoking opium, cock fighting, chewing betel nut were considered pagan, even practiced by Muslims. Whole villages were burned, the inhabitants were massacred, except the men and the young healthy girls who were sold as slaves. A virgin girl is worth a barrel of powder. (Lubis p.99)

The Dutch were called for help. Colonization did not help the population. Forced farming on poor, mountainous land was extremely difficult. All of this led to a mass exodus.]

These inhabitants of Sumatra worked the gold mines. They were miners and they naturally went where one could find gold, and later, tin. The Minangkabau settled in Melaka, gateway to immigrants, then in the Negeri Sembilan. The Mandailings mostly settled in Pahang for its gold mines or inland upstream the Sungai Klang.

Later, when the British chose Kuala Lumpur as headquarters of the colonial administration, the Minangkabau and the Mandailings were considered as “Malays”.

Between the two rivers, and in several small villages scattered in the forest, from 1830, they cleared and planted more rice fields and tapioca, built houses, fortified Bukit Nanas, opened mines, widened the paths. Because all the communications with the littoral passed by the river, there was no road. The locals, by tradition, lived on the left bank of the Klang, so the two communities shared the territory.

The men’s job was to take care of the rice fields and to clear and find tin deposits. The women were busy with their large wooden trays to extract the ore. In exchange for their sales, they bought needed tools, salt, dried fish, clothes and a little opium.

Sutan Puasa left Mandailing territory badly damaged by the Padri wars and impoverished by the Dutch occupation. He joined his community in Kuala Lumpur and made his wealth in tin mining. He went along the ore road to Melaka. In 1859, on his way back, he stopped at Lukut, which was already a flourishing mining town. There, he persuaded two Chinese merchants from whom he bought supplies, to return with him and the goods to settle in “the village between the two rivers” where he resided.

Hiu Siew and Ah Sze Keledek were looking for a location not far from the river and on the path used by the coolies on their way from the mines. Ore tin was carried back in baskets balanced on their shoulders. They cleared an area which will later be the main market square, Pasar Besar. They built their houses side by side and started their business there in 1859. Ah Sze Keledek was a sweet and easygoing man thus his nickname of Ah Sze sweet potato. Both were partners in starting and operating the tin mines. They carried on their trade in food and various goods to equip the mines. Ah Sze Keledek would become one of the wealthiest mine owners in the region.

Hiu Siew, of Hakka origin, took care of the workers from his clan who arrived in large numbers to work in the mines. He built longhouses to house them, set up a small opium den, brought in singsong girls from China, and foremost, promised to take care of the funeral rites should they die. He became the first Captain China of this mining village which was now called Kuala Lumpur.

(source: Wikipedia)

Other merchants arrived later on and opened businesses to supply the industry.

For centuries, tin had been mined in the rich deposits that followed a seam along the North-South Cordillera from Thailand to Malaysia. Dongson drums from the 6th century BCE, are made of an alloy of tin, copper and lead. They were found near Klang and along the Sungai Klang in Selangor, next to the places that landed the productions from the interior deposits.

These drums, which are found in several places in Asia, show the existence of a maritime trade in the export of tin. The port of Klang received the ore collected by the local tribes and all the profits went to the chiefs who had control of the ports and the rivers. From the 10th century, the Peninsula supplied the tin needs of SouthEast Asia.

The tin mines of Lukut in the Negeri Sembilan were in full production from the beginning of the 19th century. Sultan Muhammad, a Bugis warrior who inherited the Sultanate from the Malaysian kingdoms, reigned over the territory of Selangor and granted two members of his family, Raja Jumaat and Raja Abdullah, the authorization to search for tin seams upstream of the territory’s rivers.

Raja Jumaat operated the Lukut mines and Raja Abdullah obtained the rights to the tin reserves upstream the Klang River. In 1857, he set up an expedition, mainly financed by Baba Chee Yam Chuan, a wealthy Hokkien merchant from Melaka. Bolstered by his brother Raja Jumaat, who provided him with the workforce, he went with eighty seven miners up the Klang river and landed at the confluence between the Klang and the Lumpoor (or Gombak).

In each boat, there were ten men and a large amount of food and equipment. For this trip, the boats were loaded with rice, jars of coconut oil, tobacco, gambier, spirits and opium chest. There were also hoes with axes and other tools, baskets to transport the earth. They took weapons for their protection, muskets, gunpowder, knives and spears. Each man also had his personal package or box containing his spare clothes and a few other possessions. The river was a highway through the jungle, the main road leading to the heart of Selangor.

The boats glide in between two walls of dense vegetation. Near the estuary are the mangroves, trees with aerial roots where a crocodile can sometimes be seen with its mouth open, nipah palms that look like a palm leaf planted straight in the water. In the sweltering, warm air, the trees on the shore sometimes provided some shade. Large bamboo shoots gave a lighter green tone in this endless vegetation that the miners crossed for three long hot days, distracted only by the howling of monkeys.

Most of these young men did not survive the difficult conditions, they had to clear the jungle, to dig within the current and basically to live in the water. Most of them perished from malaria, cholera or dysentery. Other miners arrived from Lukut in boats loaded with provisions. They worked the mines of Ampang and Petaling which started to export their first ingots in 1859. The mines required significant manpower and Raja Abdullah was granted the “Kuasa Cina”. That was the right to import Chinese coolies to work in the Upper Klang mines. These arriving Chinese people were trying to escape the misery of their country. Poverty and famine caused by the defeat of China against the European powers during the opium wars. A man, the Dato Bandar, placed by Raja Abdullah, collected taxes from the crossing of rivers, a dollar for a kati or 600 grams of tin.

Other merchants arrived, and people settled along the roads in slightly raised houses:a plank platform, walls of dried mud or of woven bamboo panels and the roofs made of superimposed long leaves of attap palm or Nipah palm. These houses sheltered the family from the sun, the rain, wild and domestic animals. Unfortunately they were prone to fire and flooding when the river overflowed.

The jungle remained omnipresent. Inhabitants were allowed to grow vegetables at the back of their house, put a few pigs in a den, hens were running free.

The land belonged to the Sultan or Raja, the population was small and of different origins, from the Mandailings of the Kerincis and the Rawas of Sumatra to the Chinese. With the consent of the Raja,the property belongs to the one who clears and occupies the land permanently. If they cleared more than necessary, they could rent their land to newcomers who would farmed it.

An open cast mine in Perak during the early 20th century.

(source: https://www.nst.com.my/lifestyle/sunday-vibes/2019/05/489672/magic-and-opium-hardship-faced-early-tin-prospectors)

The village of Kuala Lumpur was developing into an important mining center.

It was a logistic platform, thanks to the numerous surrounding mines and a rich hinterland. The collected and melted tin, the various products of the jungle and the vegetables from the farms on the slopes of the Titiwangsa reef were collected to the benefit of the rest of the country. Goods, equipment, food and more men arrived.

After the death of Hiu Siew , Liu Ngim Kong, his assistant, became Captain China. The title of Captain dates back to Malacca at the time of the Portuguese occupation. It was the usual title of the chief of fairly important Chinese villages in the Malay Peninsula. In 1862 Liu Ngim Kong came to Kuala Lumpur with a young Chinese Hakka, Yap Ah Loi, whom he met in the mines of Lukut and Sungei Ujong (Seremban). Yap Ah Loi was Liu’s right hand and looked after his mines. In 1868, Liu died and Yap Ah Loi succeeded him. He was Captain China until his death in September 1885.

Image Yap Ah Loi & Sutan Puasa (https://cilisos.my/sutan-puasa-vs-yap-ah-loy-who-actually-founded-kuala-lumpur/)

Selangor Wars

The Sultan, the heads of the Royal House and the great commoners, all live along the river, drawing their income from tolls on the traffic of the river and its tributaries.

In 1867, the royal families of the Selangor tore themselves apart for the rights to export the tin of Klang and Kuala Selangor. The Selangor tin mines provided significant revenue. Six years of fighting ensued for the control of the forts on the river estuaries.

During this period of war, the miners of Kuala Lumpur seek other means and routes to convey the tin towards the ports for international trade. By thus, the tin escaped river taxmen and the Malays fighters moved towards inner Selangor to take direct control of the tin mines.

In August 1872, Kuala Lumpur fell, Its fragile wooden and palm houses were completely burned. The mines were abandoned and flooded. Yap ah Loi escaped to Klang.

There was another final battle in March 1873, following which, Yap Ah Loi repossessed what was left of the city and the adjacent mines.

The civil war could have lasted a long time without any results being seen. But it so happens that the Selangor went under British protection in February 1874 and the fighting stopped.

Yap Ah Loi’s first post-war problem was the economic reconstruction of Kuala Lumpur. The mines have turned into muddy ponds. Water wells, chain pumps, smelters and all mine equipment were destroyed. The large Kongsi houses in which the miners lived had been used as military centers and burned down during fights.

The mining workforce has been killed in combat or dispersed to other mines.

Buying equipment, pumping water from the mines, bringing back men, housing them, feeding them, all this had a significant cost. The fortune that Yap Ah Loi had won during his harbor master’s office was swallowed up in the reconstruction of ‘his’ city. Thanks to this indomitable energy, at the end of 1875, he had restored his work force to 6000 miners, compared to 10 000 in 1870.

source: G.R. Lambert & Co – Vision of the Past – A history of early photography in Singapore and Malaya, The photographs of G.R.Lambert & Co., 1880-1910

But what a dirty city!

It is a filthy town, the streets are crowded and dirty, the garbage is piled up on the roadsides. Dysentery, smallpox, cholera and other epidemics run in the population. There is no fire prevention, only a rule requiring all households to keep a barrel full of water always on the ready.

A huge hut of disjointed planks, with the roof badly thatched with palm leaves serves as a game room where a constant horde of loud Chinese and Malaysians bet and play.

In the opium barracks, which are just as badly tied up, planks used as beddings are stacked along the walls, one climbs to those at the top by use of a ladder. A lively servant burns a nugget which he places quickly on the furnace of a long pipe. The reclining man inhales in small puffs the opiate smoke which will help him to continue with his life, to endure the physical pains and the hardships of being far from his country in such difficult conditions.

In a mining town where men outnumber women, there were inevitably innumerable brothels. Most of the very young girls, bought for little from their parents, lived and plied their “trade” in squalid conditions. The houses were filthy, tiny rooms with no windows and no ventilation, so dark that a candle was lit all day long. These young girls, almost slaves, prayed to Hua Fen Fu Ren, the goddess of beauty at the little temple next door.

Father Letessier, the French priest of the Société des Missions Etrangères de Paris, who arrived in Penang in 1880 and 1883 in Kuala Lumpur, arranged a larger and healthier house for prostitutes. There were up to 300 women in 1884 and in 1899 Sister Levine of the congregation of the infant Jesus welcomed their orphans.

Captain China Yap Ah Loi is everywhere, takes care of everything, builds gaming houses and brothels, builds houses for rent, provides public services, school, police, prison, hospital, and makes considerable profits everywhere.

To manage this increasingly large administration, he relied on the organization of Chinese secret societies. Order, law, defense, development, the means of supply, the daily life of minors and the rites after death were taken care of and helped by the Kongsis.

Always, Yap Ah Loi was at the center of all aspects of social affairs. In economics, politics, administration, he took all the important decisions.

Swettenham believed that it was Yap Ah Loi’s personal determination that had prevented the Chinese from abandoning the mines around Kuala Lumpur in 1875.

source: https://www.ttgasia.com/2021/02/11/old-kuala-lumpur-east-west-connection-virtual-tour/

During the years 1875 to 1878 the British were into the habit of regularly visiting Kuala Lumpur. They began to settle in late 1879.

In 1874 Davidson was the resident “advisor” to Sultan Abdul Samad of Selangor.

Indeed, following the wars between the Chinese clans enemies in Perak, and the disputes of the sultans for questions of territoriality and successions as in Selangor, the British were brought to intervene. The East India Company first and then the Colonial Ministry offered to help the Sultans by placing a resident by their side to advise them on economic matters. Sultans and Rajas were to keep ancestral customs and religion. In reality it is the Resident who will govern.

In 1874 after the treaty of Pangkor which ratified these agreements, there was a Resident in Perak, in Selangor, in Pahang and in Negeri Sembilan.

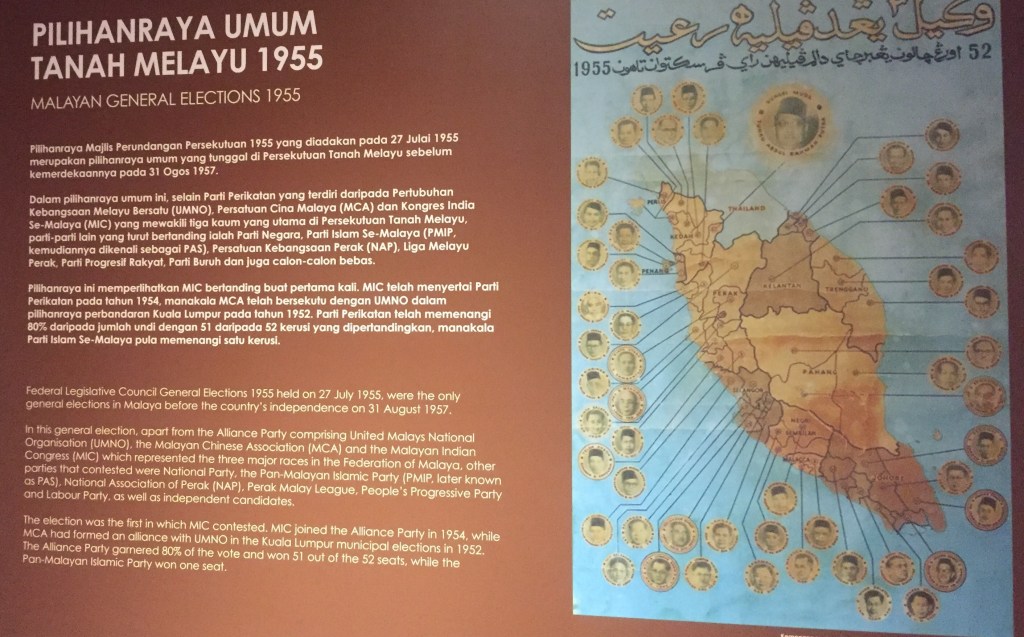

In 1895 the British thought that it was more advantageous to bring these sultanates together in a federation. That was the creation of the Federated Malaysian States, the British Malaya.

In 1896, the city developed very quickly and more and more inhabitants arrived. The place was almost in the center of the federated states and close to the straits of Melaka, thus it was decided to create a capital between the two rivers Klang and Gombak, at the muddy confluence, Kuala Lumpur.

References

Ref les Temuans: wikipedia Temuan People (consulted 6/12/2019)

Ref les Temuans: Early History

Ref Padri war: Wikipedia Padri War (consulted 9/12/2019)

Ref Dongson drums: https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2019/04/477866/dong-son-drums-found-msia-could-be-more-2000-years-old (consulté le 15/02/2020)

Ref Lubis

Sutan Puasa, Abdur-Razzaq Lubis

- Padri War, Lubis pages 57 à 147

- Étain, Lubis page 149

- Sutan Puasa, Lubis page 187 à 189

Ref Gullick

- Journal article Kuala Lumpur 1880-1895 J.M. Gullick (journal of Malayan of Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society)

- Old Kuala Lumpur J.M.Gullick

Jacques de Morgan, Exploration dans la presqu’ile malaise 1884

Jeanne Cuisinier, What I saw in Malaya

Ref prostituees: Lucy Chang Hirata JSTOR, Free indentured enslaved: Chinese prostitutes in 19th century America

À mots couverts, sur les traces de George Orwell en Birmanie