by Eric Lim

Historical societies in our country have existed since the time of the Straits Settlements. The earliest was the Straits Asiatic Society formed at a meeting on 4 November 1877 at the Raffles Library and Museum in Singapore with its parent organisation, the Asiatic Society of Bengal.

The Asiatic Society of Bengal was founded on 15 January 1784 by Sir William Jones who was a lawyer and Orientalist. When he came to Calcutta (now Kolkata) on 25 September 1783, he took up the post as a Supreme Court judge and five months later, he formed the society, receiving strong support and encouragement from the Governor General of Bengal at that time, Warren Hasting. The setting of the society was to encourage Oriental studies.

The meeting on the formation of the Straits Asiatic Society was chaired by Archdeacon George Frederick Hose, who later became Bishop. It was attended by prominent members from the expatriate communities in the three Straits Settlements states including D.F.A. Hervey (Resident Councillor of Malacca), Charles John Irving (Lieutenant General of Penang), and William A. Pickering (first Protector of Chinese of the Chinese Protectorate based in Singapore). The society started with an enrolment of 150 members. The Society’s mission was ‘to produce the collection and record of information relating to the Straits Settlements and the neighbouring countries’. Its other aims included producing a journal and establishment of a library.

The following year, the society was renamed Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society when its affiliation with the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland or commonly known as Royal Asiatic Society, was confirmed on 6 May 1878. Bishop Hope was appointed as the first President of the Society and he went on to become one of the longest serving Presidents, from 1878 to 1908. The other founding members also took up appointments in the Society and contributed actively to its journal. The first journal was named Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society; it was dated July 1878 but it was published in September 1878.

The society then went through name-change on two occasions in accordance to the political situation of the time. In 1923, it was renamed Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society when the British influence went beyond the Straits Settlements; and in 1964, it was renamed Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, after the formation of Malaysia. The name remains until today. Its office was moved from Singapore to Kuala Lumpur. The name of the journal also changed in accordance to the renaming of the society. Some of its past illustrious members were Sir Hugh Clifford, Sir Frank Swettenham, Sir Ernest Woodford Birch, Alfred Dent, and Henry Nicholas Ridley to name just a few.

Alfred Dent

Henry Nicholas Ridley

Sir Hugh Clifford

In 1930, of two more organisations were formed, namely the Malacca Historical Society and the Penang Historical Society. This was no coincidence as both states were under the Straits Settlements and had strong Western influence. Twenty-three years on, in 1953, the Malayan Historical Society (MHS) was formed, based in Kuala Lumpur. It was officially formed on 30 April 1953 at its first meeting held at the Kuala Lumpur Town Hall on Jalan Raja (the old City Hall). It was a grand inauguration attended by the British High Commissioner in Malaya, General Sir Gerald Templer, and the Malay Rulers – Sultan of Pahang, Yang DiPertuan Besar of Negri Sembilan, Sultan of Kedah, Sultan of Terengganu, Tengku Mahkota of Johor, Regent of Perak, and Deputy Raja of Perlis. Also in attendance were 200 local dignitaries – Datuk Onn Jaafar, Datuk Thuraisingam, Datuk Nik Ahmad Kamil, Datuk Tan Cheng Loke, and Tuan Za’aba, to name a few.

General Sir Gerald Templer

Datuk Mahmood Bin Mat

Tun Hussein Onn

General Sir Gerald Templer in his speech emphasized that the Society is an effort to bring all the people of Malaya together to become a unified nation in the face of time and destiny of independence. He said ‘a nation which does not look back with pride upon its past, can never look forward with confidence towards its future’. He also tasked the Society ‘to ensure that things of beauty and historic value, old and new, find their way to a place where they’ll be properly cared for, and are not allowed to moulder, forgotten and unappreciated’. He also wanted the Society to work together with other organisations and the knowledge gathered about the history to be widely disseminated to the people: ‘This is not a Society for the Government, for the educated or for any class or section of the populations, it is for everybody, and everybody has something to contribute to it’.

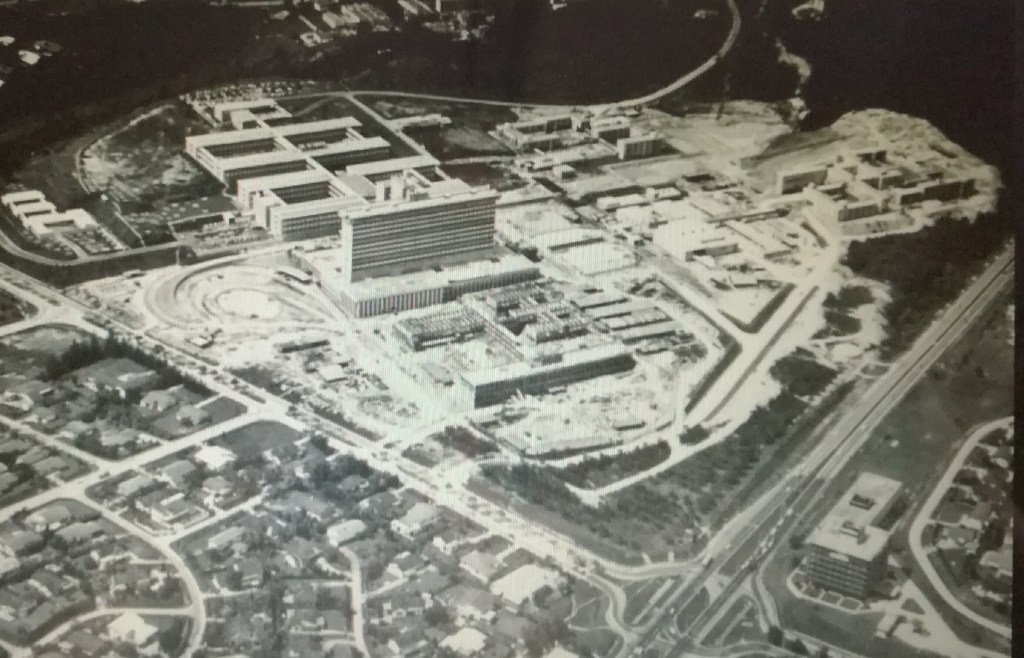

At the end of the meeting, a Council was formed and it was headed by the first President, Datuk Mahmood Bin Mat. Its office was initially housed at the National Museum, but it was later moved to Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. In 1976, the Government provided a Government house located at No.958, Jalan Hose, Kuala Lumpur to be utilised as MHS’s headquarters. Tun Hussein Onn, the then Prime Minister, officially opened the building on 31 August 1976. Later, Tun Hussein Onn managed to secure a plot of prime land in Kuala Lumpur and awarded it to MHS. On 1 December 2003, MHS officially relocated to its new headquarters at Wisma Sejarah, No.203, Jalan Tun Razak, opposite the Institut Jantung Negara/National Heart Institute.

No.958, Jalan Hose, KL

Wisma Sejarah, No.203, Jalan Tun Razak,KL

The first publication by MHS was entitled The Malayan Historical Journal; it was published in May 1954 and the editor was J.C. Bottoms. The annual subscription was twelve dollars and a single number (per issue) was priced at three dollars. In 1957, Tan Sri Mubin Sheppard took over from J.C. Bottoms and the journal was renamed Malaya in History. This journal went on for 15 years until April 1972, when Prof. Zainal Abidin Wahid took over, but from this time on (until today), the journal is produced in the Malay language and given a new name Malaysia dari segi Sejarah (Malaysia in History, in English). The late Prof. Emeritus Khoo Kay Kim was next in line to hold the editorial chair when he came on board in 1978 until 1989; he was then replaced by Prof. Dr. Nik Hassan Shuhaimi.

In addition to the journals, MHS also publishes books and monographs. Some of the bestsellers include Lembah Bujang (published in 1980), Historia (1984), Changi, the lost years (1989), Duri dalam daging (2001) and The Malay Civilization (2007). Today, the Malaysian Historical Society (Persatuan Sejarah Malaysia in Malay) maintains branch offices in all the states.

References

Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society official website [https://www.mbras.org.my/]

Persatuan Sejarah Malaysia / Malaysian Historical Society official website [http://www.psm.org.my/]

Singapore Infopedia website [https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/]