Written by Manjeet Dhillon

Melentur buluh biarlah daripada rebungnya (bend a bamboo while it is still a shoot)

This proverb, rooted in Malaysian culture, speaks to the importance of nurturing skills and traditions from a young age. In the world of Malaysian crafts, this wisdom holds true, as artisans have passed down their expertise in fibre weaving through generations. Just as a bamboo is shaped when it is still a tender shoot, so too are the hands of young artisans guided to transform natural fibres into works of art that embody both utility and heritage.

Plaited Art

Nestled in Malaysia’s lush rainforests, lies a heritage rich in natural resources. These landscapes provide the raw materials that have shaped centuries-old fibre crafting traditions. Skilled artisans harness these natural fibres, weaving them into objects that are both functional and imbued with cultural significance.

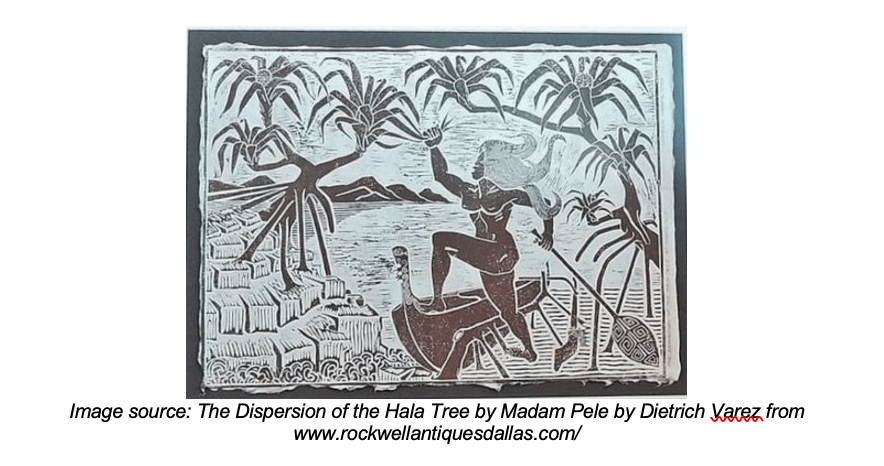

The legend of Madame Pele, the volcano goddess of Hawaii, adds a touch of mystique to the story of pandanus, a key material in local craft. When Madame Pele initially arrived, the branches of the pandanus tree entangled her canoe. In her rage, she tore the tree to shreds and scattered the pieces across the earth. Wherever they landed, they took root, providing people with a vital source for basket-making materials. Though this tale hails from afar, it highlights the widespread importance of pandanus and its role in crafting.

In Malaysia, particularly in states like Sabah and Terengganu, pandanus is prized for its use in plaiting mats and other delicate objects. The flexibility of its fibres, which bear a resemblance to palm fibre, makes it ideal for creating both practical and decorative items.

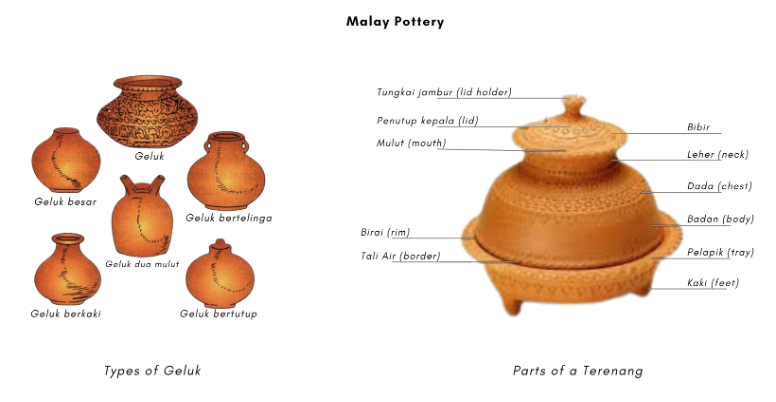

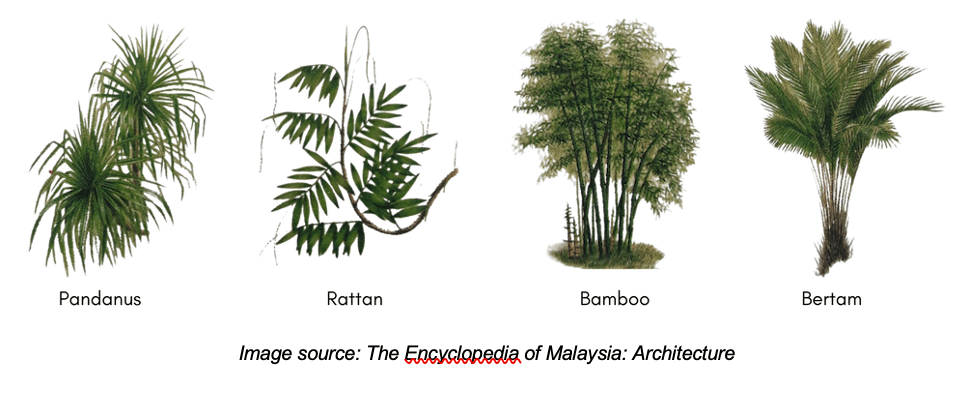

The table below summarises the variety of plant materials that are the lifeblood of Malaysian fibre crafts, alongside the objects crafted from them:

| Types of Fibres | Crafts | Description |

| Pandanus (pandan & mengkuang) | Baskets, Mats | Shorter, finer pandan leaves for delicate baskets and high-quality mats. Broader, longer mengkuang leaves for sturdier mats and woven objects. |

| Rattan & Bamboo | Baskets, Mats, Furniture, Hats | Strong and versatile. Rattan (more durable) and bamboo (split into strips) used for intricate baskets, sturdy mats, furniture, and even hats. Careful harvesting and treatment is crucial for bamboo longevity. Bamboo’s versatility extends beyond hats. It finds uses in: Musical instruments (flutes, mouth organs like the Sabah sompoton)Animal traps (various designs, made from bamboo and rattan) Decorative containers with incised designs (quivers, tobacco pouches) |

| Plants (bundusan, bemban, ferns) | Baskets, Mats, Containers | Bundusan (aquatic plant) for sleeping mats and drying pads. Bemban (similar to bamboo) for mats, hats, and baskets. Fern fibres for small baskets, containers, and decorative accents when combined with rattan or bamboo. |

| Palms (sago, coconut, nipa, bertam, silad, polod) | Baskets, Mats, Hats, Tools | Sago palms, coconut trees offer materials for household items and decorations. Nipa and coconut leaves for baskets and serving containers. Bertam and silad leaves for hats and baskets. Polod palm for tools and implements. |

The museum’s collection offers a starting point into the world of fibre crafts. By studying the materials and stories behind these objects, we gain a deeper appreciation of the relationship between art, environment, and cultural identity.

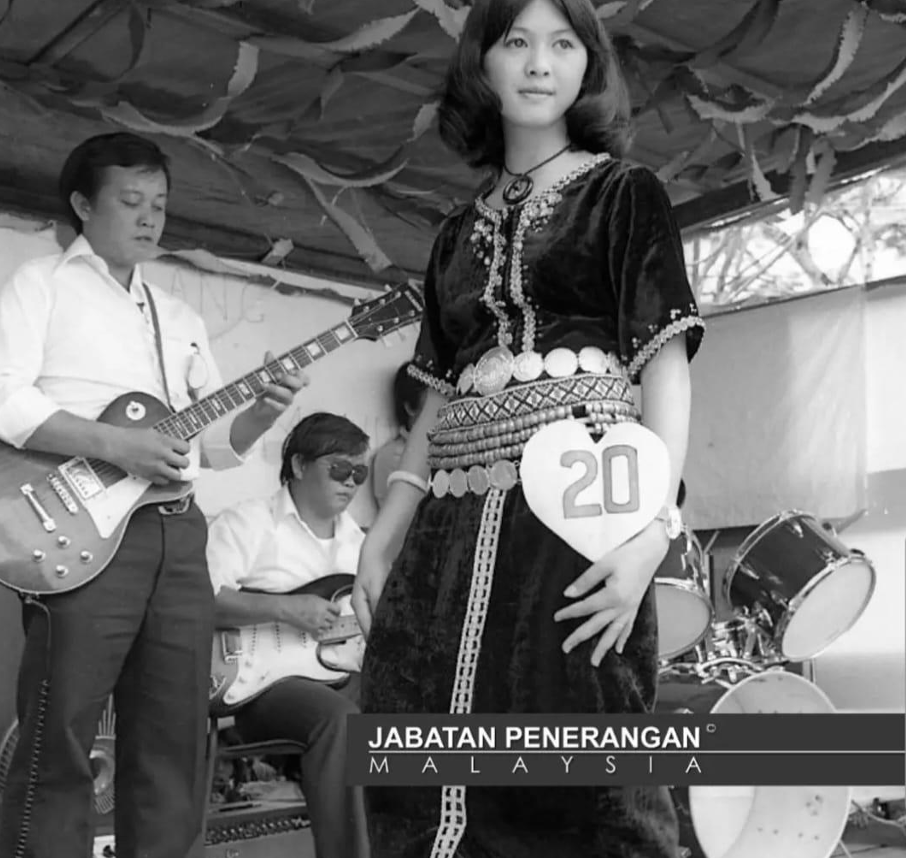

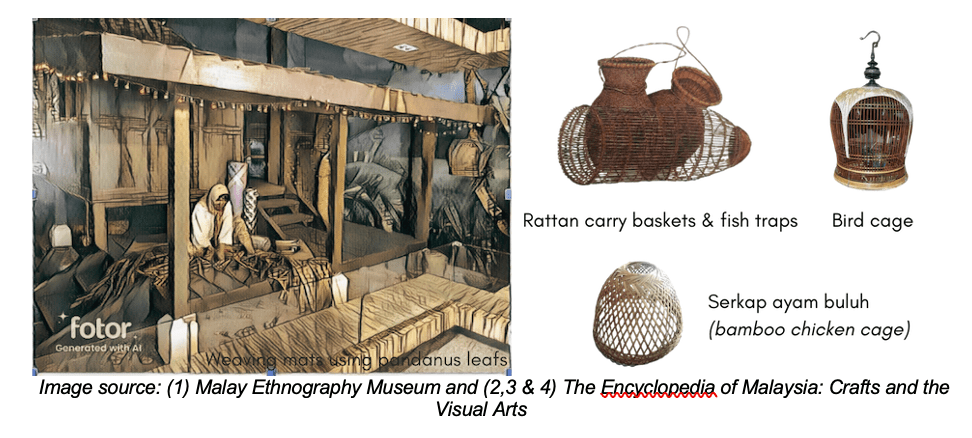

As we transition to the Museum of Malay Ethnography, we are transported to a scene reminiscent of traditional kampung life. Here, a woman’s focused expression reveals the artistry involved as she skilfully weaves strips of pandanus into a beautifully crafted mat (tikar).

Mats were among the earliest surface coverings, serving as a barrier between people and the earth during the Neolithic period. For the indigenous people of Sarawak, the forest provided essentials – reeds, creepers, and leaves for mats and baskets. A longhouse family’s room was traditionally furnished with mats for sitting and sleeping and baskets for storage, transport, and rituals. Common sleeping mats, woven from pandan leaves, are soft but not durable. Stronger mats are made from bemban canes, often with self-coloured motifs. The most resilient, crafted from split rattan and bark fibre, are used to cover and strengthen longhouse floors during festivals.

Aside from mats, the scene includes various other crafts made using natural fibres. Hanging at the edge of the veranda roof is a birdcage, crafted from bamboo or similar reed-like materials. The design of these cages varies according to the species of birds they are intended for, such as zebra doves (burung merbok) or white-rumped shamas (murai batu). While some choose to display these cages empty as a statement against keeping birds in confinement, the craft itself remains a noteworthy example of intricate handiwork.

Nearby, positioned next to the entrance door, is a barrel-shaped fish trap (bubu), also made of bamboo and secured with rattan rings. This trap, wider at one end and tapering into a cone at the other, is fitted with a separate funnel at the mouth, allowing fish to enter in one direction. These traps are particularly efficient, as they require minimal attention once set up along the riverbanks, enabling multiple traps to be placed simultaneously.

Along the left side of the kampung scene, an upside-down basket known as a bamboo chicken cage (serkap ayam buluh) is displayed. This round basket, traditionally used for trapping chickens, is crafted from bamboo, rattan, or bemban.

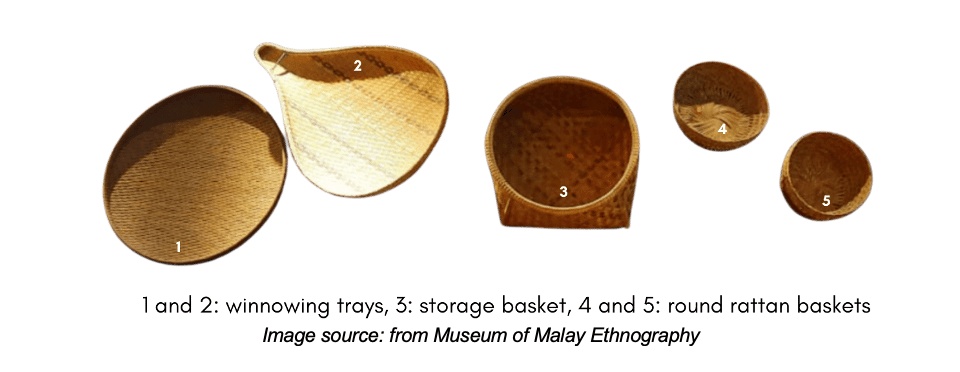

Rounding the corner, you are greeted by a display panel featuring five distinct trays (dulang) and baskets (bakul). The craft on display here is part of a lineage that reaches back to the very origins of weaving in nature itself.

Just as Mother Nature is the first basketmaker – consider how a bird intricately constructs its nest using only its beak—so too have human hands continued this legacy, crafting objects of both utility and beauty. The winnowing tray, a vital household tool, exemplifies this perfect blend of form and function. These shallow, pear-shaped, or round baskets were traditionally used to separate the paddy chaff from the grain.

Artisans would weave them from a combination of plant fibres, with bamboo, rattan, or bemban forming the surface and rim, all securely bound with sturdy rattan twine or other resilient fibres. Yet, like the natural fibres themselves, the craft faces an uncertain future as deforestation threatens the very plants essential to its practice. The decline of these materials risks not only the loss of an art form but also the cultural knowledge embedded in their creation.

Close to the exit, a section dedicated to traditional games draws your attention, featuring a display of spinning tops (gasing). Historically, the strings for these tops were crafted from the bark of the bebaru tree, along with yarn and terap rope, showcasing the resourcefulness of utilising forest materials. However, in recent times, these natural fibres have been largely replaced by nylon, highlighting the broader shifts affecting traditional practices. To the right of the vitrine display is the sepak raga, a game where “sepak” in Malay means “kick” and “raga” refers to the rattan ball used. In this game, players form a circle and keep the ball in the air by skilfully kicking it with their feet, knees, and heads.

Orang Asli Craft Museum

To gain a broader perspective on fibre crafts, a visit to the Orang Asli Craft Museum is invaluable. While their focus extends beyond mats and basketry to include a variety of intricate fibre-based handicrafts, the museum offers insights into the diverse applications and cultural significance of these arts across different communities.

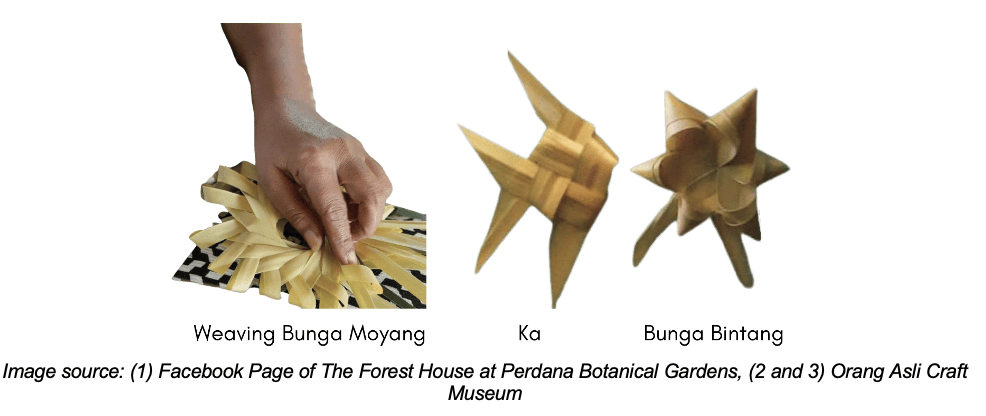

One standout example is the Bunga Moyang, a remarkable display of Mah Meri craftsmanship. These delicate ornaments, woven from palm leaves, hold significant spiritual value and are used in important rituals such as the Hari Moyang (Ancestor Day) festival and wedding ceremonies.

The palm leaf folding technique is evidence of the expertise of Mah Meri women. With over 30 distinct folds inspired by nature, these creations hold profound spiritual meaning, providing insight into the cultural traditions of this indigenous group.

Orang Asli traditional clothing, made from the bark of the Terap or Ipoh tree, reflects their deep resourcefulness and close bond with nature. Today, these garments are mainly worn for ceremonial events.

The Orang Asli’s accessories reflect their deep connection with nature and their creative ingenuity. Crafted from natural fibres like bamboo and tapioca stalks, these accessories are not only decorative but also serve as talismans believed to protect the wearer from natural disasters and malevolent spirits. The intricate designs of chains, bracelets, and other adornments highlight the community’s artistic expression and cultural heritage.

Weave Type

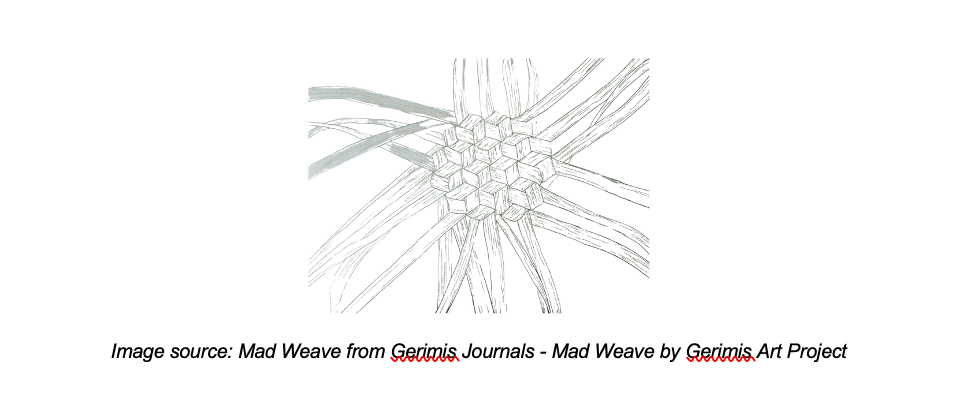

Weaving patterns play a crucial role in the functionality and aesthetics of forest-fibre crafts. A notable weave from Southeast Asia is the “mad weave” (anyam gila), or triaxial (hex) weaving, which involves weaving strips of material in three directions to create complex patterns. While I won’t explore the technical details here, let me share a fascinating tale behind this pattern:

Legend speaks of Sang Kelembai, a goblin who, troubled by humanity’s growth, tried to flee to the sky. After burning his belongings and disappearing, his woven baskets were examined by human folk who struggled to replicate the designs. Eventually, a fairy appeared, teaching them the intricate process, and thus the “mad weave” was born. The name reflects the pattern’s complexity, which demands great skill and perseverance. This story highlights how art and legend are intertwined, adding depth to the craft.

Patterns and Motifs

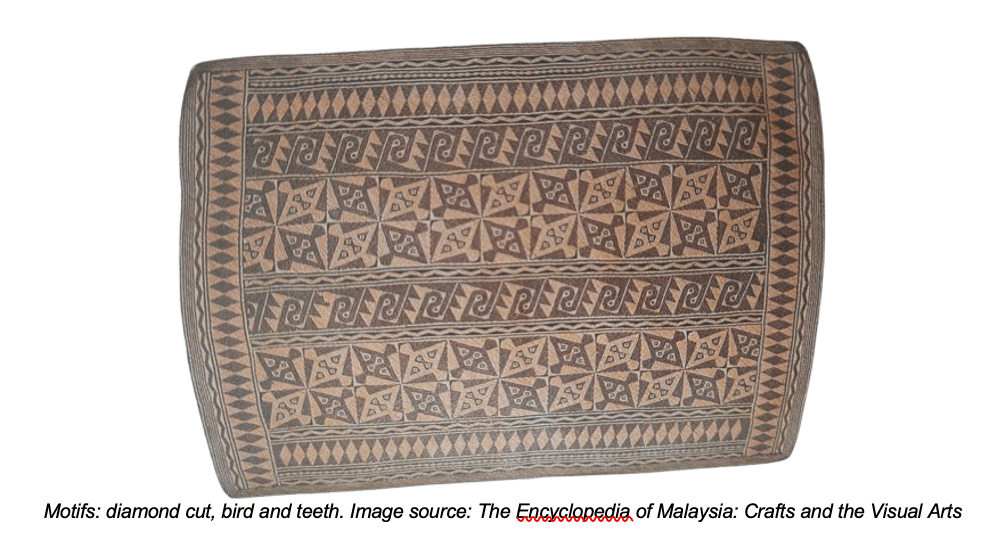

In the world of mat weaving, patterns are built from a series of motifs, each with its own story and significance. Commonly used motifs among the East Coast Malays are inspired by familiar flora and fauna, such as bamboo shoot, frangipani, clove blossom, and durian flower.

For the Iban, their monochrome sleeping mats tell tales of legendary heroes (e.g., Kumang), with designs like ‘leopard claw stealing fruit’ and ‘bird’s nest fern.’ The Penan, known for their tightly woven rattan mats, often incorporate motifs that reflect their close relationship with nature, such as fish and palm shoots.

Tools of trade

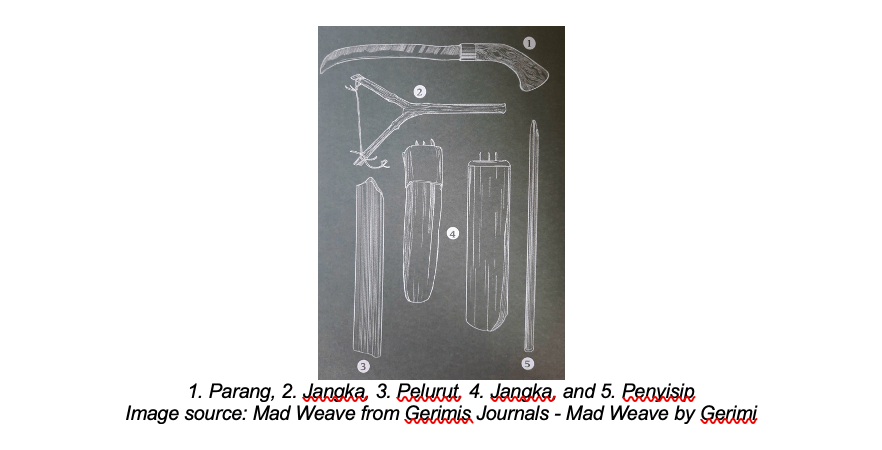

Creating these patterns requires more than just imagination; it demands the skilled use of traditional tools. The tools of the trade are as vital to the craft as the materials and motifs themselves. From simple knives and awls to more specialised instruments like bamboo splitters.

As we move from examining these patterns and motifs to understanding the tools that bring them to life, it’s essential to remember that these crafts begin with the earth itself. Natural fibres, whether they come from the forests, fields, or rivers, are the lifeblood of this art. They are shaped by skilled hands into objects of beauty and function, carrying with them stories of the land and its people. But as these materials face threats from environmental change, the future of these crafts hangs in the balance.

Finding Art in the Everyday Weaves

In our daily lives, we are often surrounded by these weavings without even realising it. Consider the checker weave on a ketupat, woven from tender coconut leaves to the thoranam decorations at Hindu temples, and even the traditional Chinese bakul sia – woven baskets used for various purposes – these everyday weavings are more than mere decorations; they are a part of our cultural fabric. So, which other hidden patterns and stories might you uncover in your daily life? Keep an eye out, and you may find that art and tradition are woven into more aspects of our world than you ever imagined.

To learn more about craft work from Orang Asli communities in Malaysia:

Reference:

- A Malaysian Tapestry – Rich Heritage at the National Museum

- The Encyclopedia of Malaysia: Crafts and the Visual Arts by Hood Salleh

- The Crafts of Malaysia by Sulaiman Othman and Others

- Sarawak Style by Luca Invernizzi Tettoni and Edric Ong

- The Kampung Legacy: A Journal of North Borneo’s Traditional Baskets by Jennifer P. Linggi

- Basketry: A World Guide to Traditional Techniques by Bryan Sentance.

- Gerimis Journals – Mad Weave by Gerimis Art Project

- A Documentation of Mah Meri Indigenous Ceremonial Attire and Ancestral Day Event Stages. https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=131710

- Rahim, Reita and Tompoq Topoh. Chita’ Hae – Culture, Crafts and Customs of the Hma’ Meri in Kampung Sungai Bumbon, Pulau Carey. https://www.coac.org.my/dashboard/modules/cms/cms~file/0e582556e1031b29bc5a39d0ba82f11a.pdf

- Barnes, Ruth. “South-East Asian Basketry” Journal of Museum Ethnography, no. 4 (1993): 83–102. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40793522

- Sellato, Bernard. “Basketry Motifs, Names, and Cultural Referents in Borneo.” https://hal.science/hal-02904063v3/document

- Mrs. Bland. “A few notes on the “Anyam Gila” Basket Making at Tanjong Kling, Malacca” Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society No. 46 (December, 1906), pp. 1-8. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41561637

- Mason, Otis T. 1909a. “Vocabulary of Malaysian Basketwork: A Study in the W.L. Abbott Collections.” https://archive.org/details/biostor-79164/page/n9/mode/2up

- Mason, Otis T. 1909b. “Anyam Gila (Mad Weave): A Malaysian Type of Basket