Written by Manjeet Dhillon

22 June 2024: History often focuses on the conquering heroes, the explorers who plant flags and claim new lands. But what about the quiet first meetings with the indigenous communities?

This often-forgotten chapter in history was recently brought to life at our focus talk thanks to Dr. Lim Teckwyn. His talk, titled “Sixteen Naked Indians: First Contact Between the British and the Orang Asli in the Late 16th Century off the Coast of Penang,” challenged our understanding of the island’s earliest encounters with Europeans.

Dr. Lim Teckwyn, an Honorary Associate Professor at the University of Nottingham, Malaysia, whose work focuses on the interface between forests, wildlife, and people, spoke about this historic encounter between British sailors and the indigenous inhabitants off the coast of Penang in the late 16th century.

Early European Arrivals

Dr. Lim first discussed the possibility of earlier European arrivals, including a Greek sailor named Alexandros in the 6th century and a possible Roman vessel around the same period. Additionally, Marco Polo’s potential voyage past the Malay Peninsula during his explorations in China is explored.

The audience is presented with a trivia question: Did the renowned explorer Sir Francis Drake visit Malaysia? The answer is no, as his circumnavigation steered south of Java on the return trip.

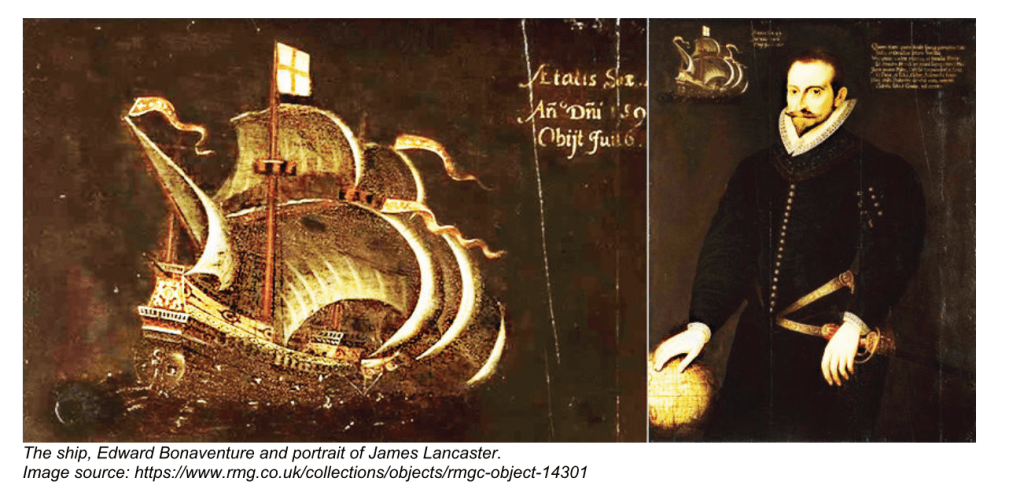

While a lesser-known figure, Ralph Fitch, holds the distinction of being the first Briton documented in Malaysia (though he arrived on a Portuguese vessel in 1588), Dr. Lim’s talk focused on Captain James Lancaster, a key figure in early British exploration of the region.

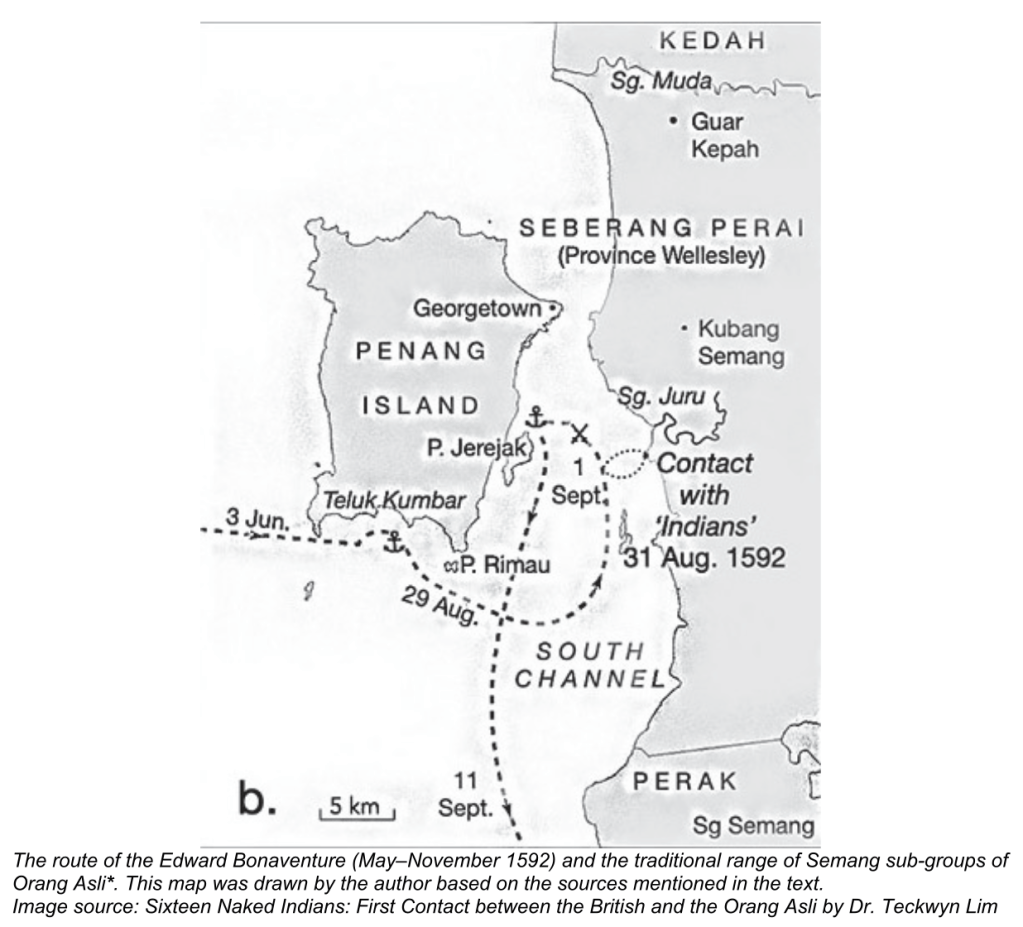

In June 1592, Lancaster arrived in Southeast Asia aboard the Edward Bonaventure, one of the first English vessels to venture into the region. His fleet, initially consisting of three vessels, was reduced to one by the time it reached Penang, largely due to the ravages of scurvy (an illness caused by vitamin C deficiency) and the loss of ships during the journey.

The Encounter

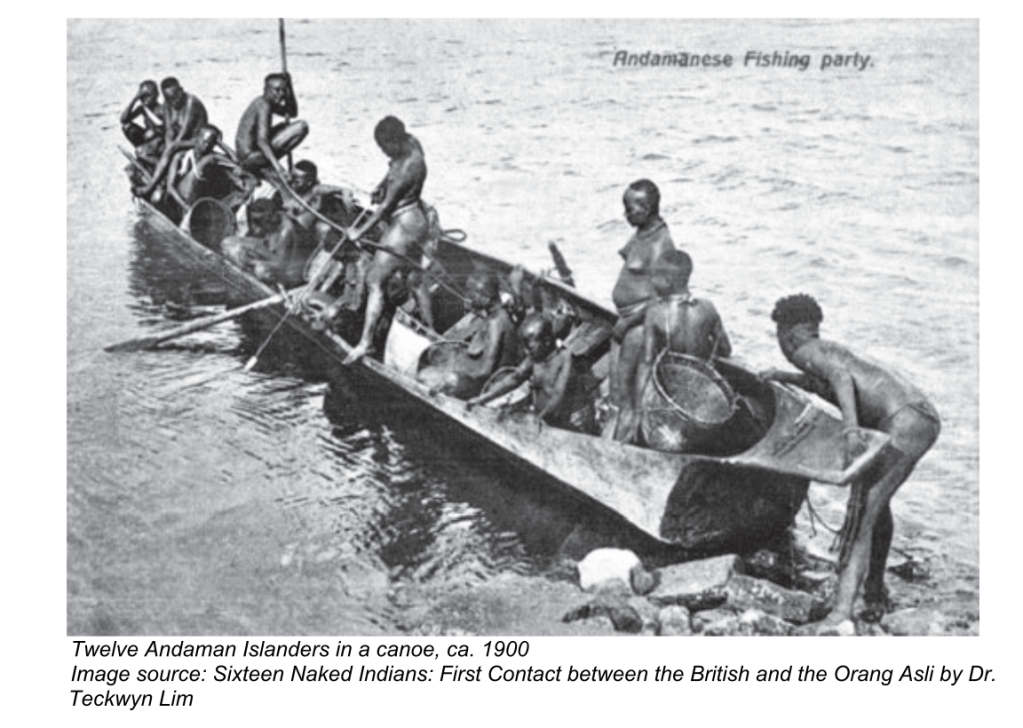

The first recorded interaction between Lancaster’s crew and the indigenous people occurred on the mainland near Penang on August 31, 1592. According to the journal of Lancaster’s first mate, Edmund Barker, the British sailors initially observed signs of recent human activity, such as burning fires, but encountered no people until the following day. When they finally met the locals, they described them as “sixteen naked Indians” in a canoe. This brief encounter, however, offered valuable clues about the identity of the islanders.

Dr. Lim clarified that the term “naked” in Elizabethan English often referred to people who were not fully dressed by contemporary European standards, rather than being completely unclothed. These indigenous people, likely wearing minimal attire, engaged in a friendly exchange with the British sailors, promising to provide fresh victuals (fresh fruit) to help restore the sailors’ health and allow them to continue their voyage.

Dr. Lim’s research suggests that this encounter proved to be a valuable learning experience. On a subsequent voyage, Lancaster implemented a preventative measure by regularly providing his crew with lemon juice, effectively combating the illness.

Orang Asli or Malay? Examining the Clues

The identity of these “naked Indians” became a subject of exploration for Dr. Lim. He suggested that the term “Indians” in this context referred broadly to non-Muslim inhabitants of the region, as opposed to the Muslim Malays, who were often referred to as “Moors” by European explorers of that era. This distinction is crucial in understanding the nature of the encounter and the cultural background of the indigenous people involved.

The canoe described in Barker’s journal, likely a dugout with an outrigger, is consistent with those used by the Orang Asli and other indigenous groups in the region.

Dr. Lim’s extensive research into the Orang Asli provides further context, suggesting that these people were part of the diverse and complex network of indigenous communities inhabiting the Malay Peninsula.

While the evidence for this encounter may be circumstantial, it holds significance as the first recorded contact between the British and the Orang Asli. It offers a glimpse into a period where European influence in the region was nascent and the Orang Asli way of life remained relatively undisturbed.

A More Inclusive Narrative

The Orang Asli, the indigenous people of Peninsular Malaysia, were likely the first to greet the European sailors. Their presence sheds light on a facet of Penang’s history that has been overshadowed by later colonial narratives. This chance encounter, though brief, reminds us to consider the perspectives of the Orang Asli, who inhabited these lands long before European arrival. Understanding these early interactions allows for a more complete and nuanced understanding of Malaysia’s past.

Q&A Session Highlights

The talk was followed by a Q&A session that shed further light on Dr. Lim’s research and the broader context of European exploration in Southeast Asia. Here are some key takeaways:

● Captain James Lancaster’s Voyages: An audience member inquired about Captain Lancaster’s other voyages. Dr. Lim confirmed that Lancaster undertook several expeditions, and the encounter with the Orang Asli likely occurred on an earlier voyage before his more famous exploits aboard the Dragon, a ship funded by the East India Company. He also mentioned that Captain Lancaster was likely knighted for his achievements on a separate voyage.

● The Use of the Term “Malay” Another interesting question explored the possible use of the word “Malay” by Europeans at that time. Dr. Lim suggested that while contact with Malay-speaking people in other parts of the archipelago likely occurred, the term “Malay” in the English language might have been introduced by explorers like Magellan, whose journals were translated soon after their voyages.

● Denisovans The discussion briefly touched upon Denisovans, an ancient human relative. Dr. Lim acknowledged ongoing research on their possible presence in Southeast Asia (referencing twelve skulls found near the Solo River in Indonesia). Their presence is hinted at through DNA markers. Aboriginal Australians, Papuans, and some Filipinos possess Denisovan DNA, suggesting interbreeding between these ancient humans and early modern humans in the region.

Recent genetic studies paint a fascinating picture of human migration in Southeast Asia. The Orang Asli share DNA with people from Melanesia, suggesting ancient connections.

Note:

The Orang Asli (meaning “original people” in English) are the indigenous communities of Peninsular Malaysia. They encompass a diverse network of sub-ethnic groups, each with its own language and cultural practices.

Traditionally, many Orang Asli groups have lived semi-nomadic lifestyles, attuned to the rhythms of the rainforest and practising activities like shifting cultivation, hunting, and gathering.

This encounter with the British sailors in 1592 sheds light on a period when their way of life thrived in relative isolation. Today, the Orang Asli face challenges related to land rights and modernisation, yet their culture and connection to the environment continue to be celebrated.