By Eric Lim

This year, we commemorate our 67th Independence Day with the theme ‘Malaysia Madani : Jiwa Merdeka”. And we took full advantage of the extended public holiday to visit the state of Perak, which incidentally is embarking to boost and revitalize its tourism sector by promoting the “Visit Perak Year 2024” campaign.

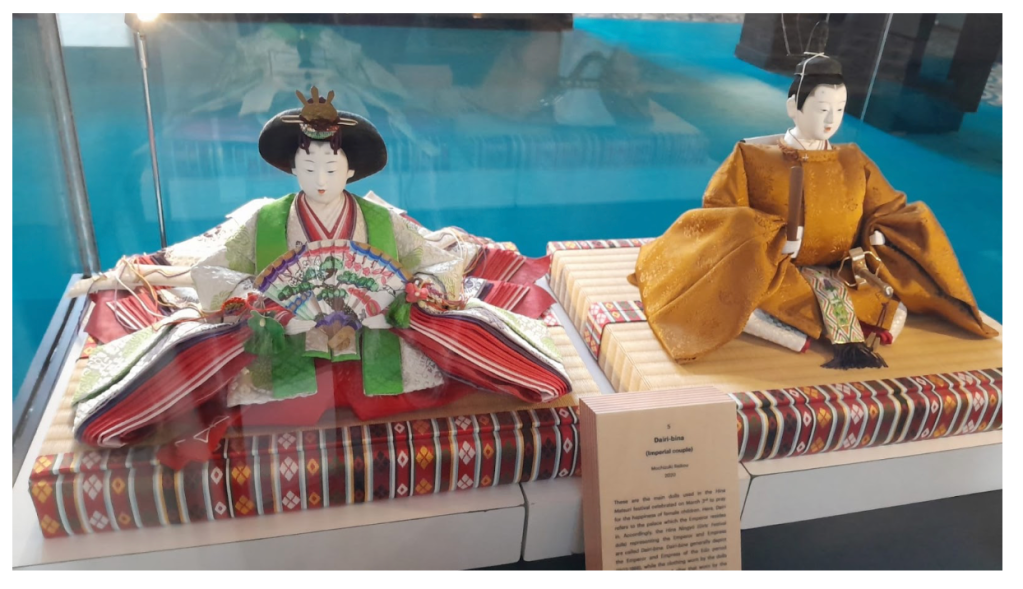

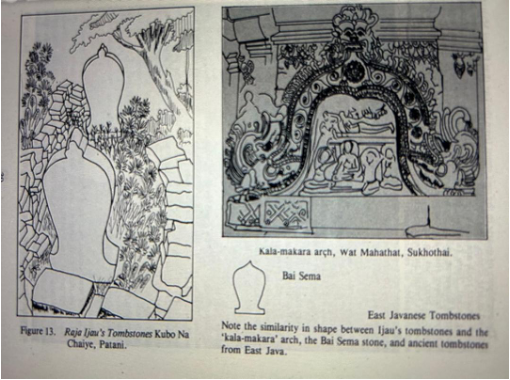

We took off early in the morning and exited Bukit Lanjan to join E1, the North South Expressway – Northern Route. Together with E2 which heads the Southern Route, it forms a section of the Asian Highway 2 (AH2) that connects Denpasar in Indonesia, through Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Myanmar, India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan and finally ends at Khosravi in Iran. We made a stop at Bidor for breakfast. The town’s claim to fame can be pinpointed to the discovery of the standing statue of the eight-armed Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara which is permanently on display at the National Museum. The statue was found in a tin mine belonging to the Anglo Oriental company in 1936 and one of the arms was already broken when it was found. The bronze statue stands at 93 cm and weighs 63 kilograms. It is believed to date back to the 8th – 9th CE during the period of the Gangga Negara, a Hindu kingdom which was centered at Beruas. This artifact has been categorized as an Important Object among the 173 heritage items (and counting) declared as National Heritage in our country.

Statue of Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara

Photo : Avalokiteshvara | Official National Museum Website.

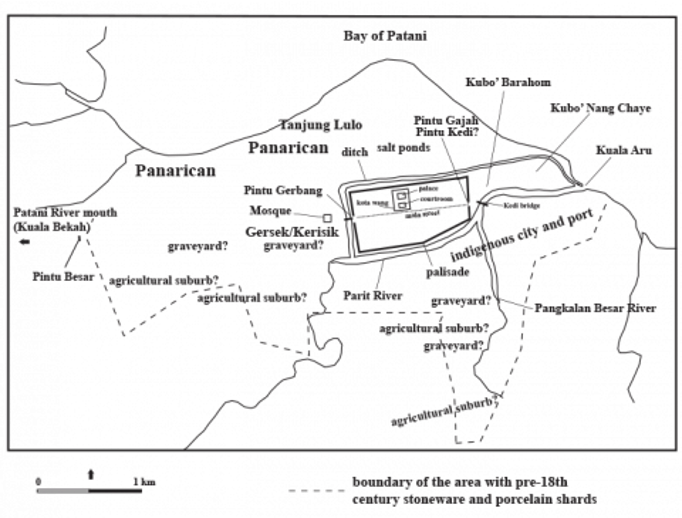

From Bidor, we travelled about 43 km west to the town of Teluk Intan, the administrative centre for the Hilir Perak district and the largest town in the south of Perak. Navigating through the town, we can use the Teluk Intan Fun Map as our guide to explore the key historical sites and landmarks. Each landmark is numbered based on the Fun Map, making it easy to follow along as we discover each location. The area was first explored at around the beginning of the 19th CE by a Mandailing trader by the name of Mak Intan who subsequently named the settlement Pekan Mak Intan. After the signing of the Pangkor Treaty in 1874, the town was made the administrative center and base for the British. Later, when Hugh Low was the British Resident of Perak, he requested for the creation of a new administrative town. General Sir Archibald Edward Harbord Anson took the task and drew up plans for its expansion. He was then made the First District Officer. When he retired in 1882, the town was named after him, Teluk Anson (Anson Bay). Next came the railway service. Despite an initial dispute on the route, it was finally settled after the construction of a bridge across Bidor River (No.10) that reduced travelling time from Teluk Anson to Tapah Road. With a total length of 550 ft (168 metres), the railway bridge was the longest ever constructed at that time. The line was opened in May 1893, linking the town to the network to the north and south of the peninsula. A year later, on 17 September 1894, a night mail train was derailed after a bull elephant charged at it while defending its herd (No.12). Meanwhile, Teluk Anson continued to develop into a busy port, so much so that it was the second most important port after Port Klang (Port Swettenham) from 1934 to 1940. It was also used as a processed oil storage terminal for Shell after the port overhauls in 1947. At the centenary celebration of the town’s establishment in 1982, Sultan Idris Shah renamed it back to Teluk Intan (Diamond Bay).

The railway bridge across Bidor River in 1893 / Photo : BERPETUALANG KE ACEH: The old railway bridge at Teluk Intan

The derailment on 17 September 1894 / Photo : 127 Years Ago, An Elephant Literally Fought A British Steam Engine Train In Perak | TRP

Today, one can visit the numerous historical sites located around the town – some are well preserved, some in need of restoration and others are missing or lost.

Talking of the latter, the railway service ended its run in 1991 due to the shortage of passengers and the train station is repurposed into a driving academy. The old railway gate can still be seen in the town (No.11). The railway bridge across Bidor River has been converted for pedestrian and motorcycle use and Shell has relocated its processed oil storage operations to Lumut. The skull of the elephant that rammed into the train in 1894 is currently on display at the Perak Museum in Taiping.

Of the many tangible heritage sites in the town, the Leaning Tower of Teluk Intan (No.1) must surely be the most iconic. Originally built as a water tower in 1885 by a local contractor by the name of Leong Choon Cheong, it started to tilt four years after its completion due to an underground stream. In July 1941, a decision was made to demolish the tower ahead of the impending war but two months later, the decision was reversed and it survived through the war. Now it serves as a clock tower. The first clock installed in 1894 was bought from the world famous clockmaker, James Wilson Benson of Ludgate Hill, London. The adjacent street (Jalan Ah Cheong) is named after the contractor in honour of his contribution to the town. The tower was declared a National Heritage Building by the Malaysian Heritage Department in September 2015.

Leaning Tower of Teluk Intan / Photo : Eric Lim

Also situated at the town centre, is the War Memorial (No.9) which is in the form of a boulder that sits on top of a base made of solid stone. It was unveiled to commemorate former residents of Hilir Perak district who fell in the Great War of 1914 – 1918 (World War 1).

The building of Teluk Intan’s old Courthouse (No.8) was completed in 1893 and besides providing judicial functions for the district, it was also used as a church for the Anglican Christians community on every Sunday for their weekly prayer service. It lasted until 1912 when a new church, Church of Saint Luke the Evangelist was inaugurated. It was a small wooden building until it was renovated in 2001. Other places of worship that stood the test of time are –

St. Anthony Of Padua (No.5) which was originally built in 1894 but it was destroyed in a fire in 1914. The current church was built in 1922 and was consecrated by Bishop Jean Marie Merel the following year.

Hock Soon Keong Temple (No.4) was built in 1883 on a piece of land that was offered by General Sir Archibald Edward Harbord Anson when he was still in office. The generous offer was a sign of appreciation to the community when he made a miraculous recovery from his serious illness. The temple was built according to architectural concepts from Southern China.

The Sri Thendayuthapani Temple (No.6) was built in the late 1890s with contribution from the local Chettiar community. They brought in the finest teak wood from Myanmar to be used for the foundation of the temple and also a silver chariot from India in 1932 for their annual festival.

Also located in the town is the Indian Muslim Mosque which is believed to be built in the late 19th CE or early 20th CE. It is the oldest mosque built in Teluk Intan.

These sites continue to play an important role in the local community. However, the following two sites are currently in need of restoration:

Old Police Station (No.7). Built in 1882, the building was initially used as a tax collection center and customs office. Later it was changed to a police station. During the war, the Japanese Military Police turned it into an interrogation centre..

The Old Palace of the Young Raja of Perak (Istana Lama Raja Muda Perak) was built in 1924 at a cost of $24,000. The first Raja Muda of Perak to reside here was the late Sultan Abdul Aziz who became the 31st Sultan of Perak while the last was the late Raja Muda Ahmad Siffuddin Ibni Almarhum Sultan Iskandar who died in 1987.The current Sultan of Perak, Sultan Nazrin Shah was due to stay here but he stayed at the palace in Ipoh instead. While the palace was in use, Teluk Intan was known as a Royal Town.

Besides the heritage sites, Pulau Bangau (No.2) or Stork Island, in Sungai Perak is a new attraction. Currently home to more than 30,000 birds of various species and amongst them, there are ten species of stork (shorebirds) like Bangau Besar (Great Egret), Bangau Batu (Pacific reef Egret), Bangau Bakau (Great billed Heron), Banbau Cina (Chinese Egret), Bangau Kecil (Little Egret), Bangau Kendi (Medium Egret), Bangau Kerbau (Cattle Egret), Bangau Paya (Purple Heron), Asian openbill heron and Striated Heron. There are also other interesting locations to explore like the shipyards, fish breeding farms, furnace of a sunken ship, just to name a few.

For those who take the evening cruise, an added attraction is to watch fireflies light up the night with a display of flashing lights. The Pulau Bangau fireflies are of the Pteroptyx tener variety.

Teluk Intan Fun Map / Photo : Portal Rasmi Majlis Perbandaran Teluk Intan – Latar Belakang

After the river cruise, we drove to Bagan Datuk (previously Bagan Datoh). Bagan Datuk was upgraded into a full district in 2016, the 12th district in the state of Perak. It was once a major coconut producer around the end of the 19th CE until the middle of the 20th CE. We made a brief photo stop at Dataran Bagan Datuk. And located within walking distance from the square is the Tuminah Mosque Complex. This floating mosque concept on the banks of the Perak River is the latest and unique attraction in the district. It is the third floating mosque in Perak.

Photo stop at Bagan Datuk / Photo : Eric Lim

Tuminah Mosque Complex / Photo : Portal Rasmi Majlis Perbandaran Teluk Intan – Latar Belakang

It was another 10 km drive from Bagan Datuk to our resort at Sungai Burung, located on the coast. As it was still early after our check-in, we decided to visit the Sunflower Garden. This garden was established in 2020 and since its inception, has garnered a lot of interest through social media. Some commented that they do not have to go abroad to look at the sunflowers as there is one in our very own backyard. The owners have also decorated the garden with many visually appealing props that made the place very instagrammable. Some interesting fun facts about sunflower –

*The binomial name for the common sunflower is helianthus annuus, and it is indigenous to Mexico, central and eastern North America. It was brought to Europe by the Portuguese in the 16th century and by the 19th century, commercialization of the plant took place in Russia, Ukraine and South east Europe until today. The sunflower is the national flower of Ukraine.

*Sunflowers can remove toxic elements from soil like lead and uranium, and have been used in clean up operations at both Chernobyl and Fukushima.

*Sunflowers have developed an internal clock in their system where they track the sun movement akin to humans with the circadian rhythm. At dawn, sunflowers face east to greet the first rays and continue to move with the sun until sunset in the west. Overnight it swings back to the east. This movement is called heliotropism, but it only happens when sunflowers are still young. A matured sunflower (when it blooms) will remain steadfast facing the east. This is to promote pollination.

Sunflower Garden at Sungai Burung / Photo : Perak Sky Mirror / Nine Island Agency Sdn Bhd | Bagan Datoh

Later, we were offered buggy rides to visit the small fishing village of Sungai Burung. Then it was time for dinner where we had a wide variety to choose for our D.I.Y seafood steamboat. As it was a public holiday, the restaurant was filled to the brim with tourists. Happily, we had filled our tummies and were all set for the next item on our itinerary i.e the Blue Tears tour (it is mentioned as Blue Sand tour in the pamphlet). We were taken out to sea and after a while, the boat was kept in an idle state, and suddenly, as if by magic, the guide scooped flashing sand out of the water using a net. Yes, it was stunning to see that the sand was flashing blue lights however not for long, as soon as it touched the deck, the lights just faded out.

The Blue Tears / Photo : 7 Dreamy Locations To Catch Sight Of Blue Tears In Malaysia – Klook Travel Blog

The Blue Tears is a natural phenomenon caused by Dinoflagellates, a type of plankton (microscopic marine organism) and they are traditionally classified as algae. They have characteristics of both animals and plants, and live near the water surface where there is sufficient light to support photosynthesis. The blue light glow by dinoflagellates is a result of it being bioluminescence. Bioluminescence is light emitted by living things through chemical reactions in their bodies. Luciferin is the compound that actually produces light and dinoflagellates produce it on its own through photosynthesis. Dinoflagellates bioluminesce in a bluish-green colour. When the water becomes fertile, the algae will reproduce and will result in a rapid and excessive growth of plankton population known as algal bloom. The algal bloom will cause the surface of the ocean to illuminate at night (Blue Tears). Fireflies are also bioluminescent organisms and they glow in the yellow spectrum.

Though we were quite disappointed not able to experience the maximum impact of the Blue Tears, the main highlight was still ahead, just under twelve hours away. The next morning, we were advised to wear vibrant, multi-coloured outfits. After a hearty breakfast and a cup or two of ‘kopi’, we relaxed in the sea breeze before heading out to the Straits of Malacca to experience and enjoy the Sky Mirror.

The Sky Mirror is simply a large, flat area with water that reflects the sky. The concept of Sky was inspired by Bolivia’s Salar de Uyuni, the world’s largest salt flat, which spans 4,000 square miles. At 3,656 metres above sea level, the flat holds 10 billion tons of salt, and beneath it lies 70% of the world’s lithium reserves, used in batteries for electric cars and mobile devices. Visitors flock to capture the striking mirror effects and perspective photos.

The introduction of Sky Mirror as a tourist destination in our country started less than ten years ago in Selangor. Since then, it has garnered a huge following thanks to the uploading of ‘crazy photos’ on social media. In our case, the mirror effect takes place in the Straits of Malacca, on a seabed that appears above sea level at low tide thus exposing vast sand flat for a few hours in the morning. Here are some ‘crazy photos’ that we took during our trip. If you do not want to miss these fun activities, you know where to go. Now, you do not have to travel halfway around the globe to do it, just do the ‘cuti cuti Malaysia’ way.

Photos by kind courtesy of Jane Ng, Everfit Yoga.

References

Avalokiteshvara | Official National Museum Website.

Taiping Museum to feature elephant skull from historic 1894 collision

Portal Rasmi Majlis Perbandaran Teluk Intan – Latar Belakang

In Perak, Pulau Bangau attracts domestic, foreign tourists | Malay Mail