A MV FOCUS TALK by Professor Daniel Perret (27th May 2024)

By Hani Kamal

Professor Daniel Perret, the head of the French School of Asian Studies at the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, History Department, Universiti Malaya, is currently serving as a visiting professor at the same institution. His research specialises in the history of epigraphy and archaeology in proto-urban sites throughout Southeast Asia. His presentation, titled “New Research into the History of the Patani Sultanate in the 16th-17th Centuries,” focused on investigating the historical aspects of Patani.

Perret and Jorge Santos recently conducted a translation of a substantial collection of articles sourced from European, Japanese, and Chinese historical records. These sources shed light on the extensive trade relationships established by European powers such as the Portuguese, Dutch, and British in Patani during the 16th and 17th centuries. Through their study “Patani Through Foreign Eyes: Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries,” published in 2022, Perret and Santos meticulously translated and re-analysed these foreign historical manuscripts detailing the dynamic events within the Patani Sultanate, particularly the reign of four successive queens.

Perret’s presentation emphasised the significance of combining physical evidence, such as monuments and artefacts, with information extracted from ancient manuscripts. These elements provide valuable insights into the events unfolding in the 16th and 17th centuries, showcasing Patani as a pivotal trading hub in the Eastern Seas under the influential rule of these queens. Examples of such artefacts include ancient royal tombstones such as Batu Acheh gravestones, a sketch of the old citadel and manuscripts documenting the legacy of the Patani queens.

Background of Patani

The word Patani originated from the Malay word “pantai ini” (this beach), and as mentioned in Hikayat Patani, it is where a white mouse deer was spotted. In the early days, Patani covered the entire Thai provinces of Patani, Yala, and Narathiwat and included parts of northern Kelantan in Malaysia. According to Hikayat Patani, which was recorded by various authors between 1690 and 1730, the early history of Patani must have been established in the early 2nd century when the strategic cape of Patani was sought after by ships travelling straight from the Gulf of Siam across from the Vietnamese point before going to the Malay Peninsula ports. According to Teeuw and Wyatt’s translated version of the “Hikayat Patani: The Story of Patani”, published in 1970, Patani was believed to be Langkasuka (208BC), situated in a very strategic location geographically ideal for a very complex Asian trade system. Professor Wheatley, in his book The Golden Khersonese, A Study of Asian Historical Geography, concludes that Langkasuka transitioned into Kota Mahligai (now Yarang). But it became almost non-existent when the Srivijaya empire became powerful in the 8th and 9th centuries, dominating the Malay Peninsula. There were major power struggles among the Siamese, Khmer Empire, the Burmese Mon/Pagan Empire, the Cholas, and the Javanese in Southeast Asia during the same period. It is not clear as to when Kota Mahligai became Patani before 1500. However, three main themes emerged in the literary sources on Patani: Siamese influence, its conversion to Islam and its economic rise. (Bougas, 1990: Pg 114)

The peak period in Patani’s history is typically identified as the 16th and 17th centuries. However, by the latter part of the 17th century, the influences of Siamese Sukhothai and Ayuthaya began to dominate the region. In 1902, Siam further weakened Patani’s authority by dividing it into seven districts. The Treaty of Bangkok in early 1909 officially acknowledged Siam’s sovereignty over all the northern Malay territories, thus sealing the fate of Patani ever merging with the peninsula Malay states. Consequently, the Sultanate of Patani was dissolved, and its heir resided in exile in Kelantan. Following World War II, the Treaty of Songkhla in 1949 solidified the inclusion of Patani and the other northern Malay states into Thailand. The ongoing conflict and struggle for independence in Patani persist to this day amid continuing disputes.

The organisation of the Patani capital in early 17th CE

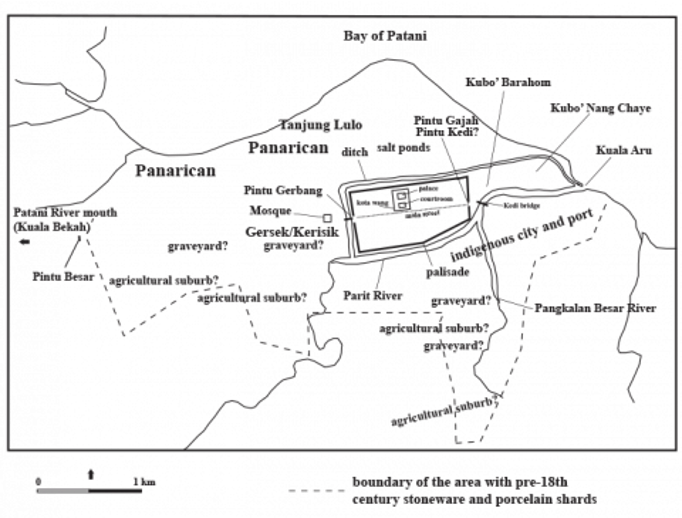

No maps portraying Patani during the 16th and 17th centuries have been discovered. The sole visual representation from that era is a depiction of the city, displayed in Figure 1, which was crafted by Jacob van Neck during his visit to Patani. An intriguing account from 1678 suggests that two trading officers from the British East India Company voyaged to Patani specifically to procure this city map, subsequently dispatching it to their office in Ayutthaya. Regrettably, Perret noted the absence of this document in the British Archives.

The illustration or sketch of the Patani capital, featured in Figure 1, offers a broad overview of the city during the 16th century. Jacob van Neck’s rendering highlights key locales such as the palace, the citadel, various town districts, the merchants’ quarters, and the harbour. This visual portrayal of the Patani capital’s layout is derived from on-site surveys, oral traditions and written accounts documented by diverse sources, including the Malay, Dutch, Portuguese, British, Japanese, and Chinese. Based on field data, it is inferred that this depiction dates back no further than 1584, a pivotal year marking the ascension of the first queen.

In Figure 1, Panarican—which appears eight times in the rutter—or “Penarekan” in Malay, denotes the dragging of boats across the river. “Tanjung Lulo”, appearing seven times in the rutter, is described as a headland on the sandy coastline with two bastions, including the largest in the city and its main gate. Tanjung Lulo is certainly the Tanjung Lulup mentioned once in the Hikayat Patani. Kuala Baca, a sandy beach area, was a town in Patani—it is the “Kuala Becha” mentioned in Hikayat Patani, as well as Dutch and Portuguese sources. On the west coast of the citadel, Garzen, which is frequently mentioned, is likely “Kerisik”, meaning coarse sand. This location fits well with the current location of Ban Kru Se (Kerisik). The “PINTU GARBA” mentioned is the Pintu Gerbang (main gate) in Hikayat Patani, large enough for elephants to pass through, also referred to as Pintu Besar (Big Gate) at the west of the Citadel. Kuala Saba (river mouth of Saba River), north of Panarican, has disappeared in the last four centuries.

Fig. 1. Sketch map of the city of Patani (late sixteenth – early seventeenth centuries) (adapted from Perret et al. 2004).

Portuguese sources—recounting a Portuguese attack on Patani in 1524—recorded Chinese living in brick houses in Patani. Dutch sources cite that Dutch lodges were built with bricks and that the English and Dutch lodged near the bay. The rutter also described the city as having a defence system that served as a channel for communication. According to the sources, the citadel walls were about eleven feet high and seemingly had a very imposing fort. Foreign sources also noted the formidable size of a cannon placed near the Pintu Gerbang. The royal family and Orang Kaya lived within the citadel. A small mosque was also located near the citadel. Salt pans, where salt was produced, were situated north of the citadel.

Similar sources also mentioned how the palace walls were adorned with gilded panels and other wood carvings. This is probably the earliest mention of woodcarving in the northeast state of the Malay Peninsula. The balairung (main royal hall) was described as abundantly decorated with gilded material and velvet-trimmed dais, and the queen sat by a large gilded window. A royal graveyard is also mentioned, and, based on oral tradition, the first Sultan of Patani could have been buried there. The tombstone could have been moved out of the city.

Unfortunately, the city was destroyed by fire four times between 1524 and 1613. By 1786, the Siamese had destroyed the entire city in retaliation to Patani’s assertion of independence.

Ancient Islamic Tombstones

Perret divided the tombstones he found in Patani into three styles: Batu Acheh, Batu Patani Brunei and Bai Sema.

The Batu Acheh tombstones, found across the Malay world, offer a unique insight into the region’s Islamic history. Characterised by sophistication and widespread distribution, these tombstones hold rich epigraphical data. Originating possibly in the 15th century around Pasai, these sandstone monuments signified a departure from local traditions. Although sharing similarities with architectural styles from Central Java and Siamese funerary monuments, batu Acheh was primarily reserved for sultans, high-ranking individuals, their relatives, and possibly affluent merchants. Despite a decline in the 18th and 19th centuries, a resurgence of batu Acheh can still be observed in regions like north Sumatra (Barus), Kedah, Pahang, and Penang.

Batu Acheh tombstones are generally made of sandstone, granites, quartz, river pebbles, marble, cement and wood. The types of material used for the tombstones also give an indication of the economic strength of the state—intricate quartz was used during the 17th century while wood and natural stone were used when the state was in decline. The Batu Acheh tombstones were imported from Acheh and had different shapes, motifs and Islamic Khad inscriptions. The grave of Raja Kuning (the last Queen of Patani) is marked with quartz markers found in Kubo’ Barahom.

Batu Patani Brunei (Figure 2) are tombstones brought in from Brunei. Brunei and Patani were trading partners between the 15th and 17th centuries. Two such grave sites were identified with Batu Patani Brunei in Kampung Parit and Kampung Pintu Gajah. The design was very specific to that found only in Patani and Brunei. It has Chinese motifs, such as clouds. One of the tombstones is believed to be that of the son of the founder of the Sultanate of Patani in the 15th century. It has an Arabic calligraphic inscription stating the son of the sultan on the south side and “Malik bin Mohamad” on the north direction. Unfortunately, no dates were found. Perret postulates that these tombstones could belong to the Brunei people who lived and were buried in Patani.

Fig. 2. Tombstone at Kuboʼ Barahom (D. Perret-EFEO, 1999)

Roeloefsz (1601-2) mentioned the existence of royal graves on the Seberang peninsula and this is the only source citing this interesting information. There were few tombstones found but no indication of a royal one. Ludvik Kalus (2004: 193-206).cited that there were two tombstones found and one of them believed to be the grave of the first Sultan of Patani (Fig.2).

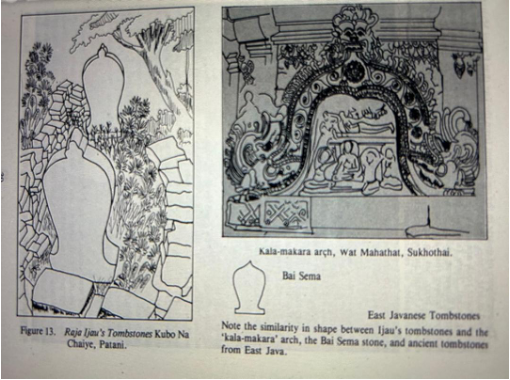

According to oral tradition, Raja Ijau’s tombstone was made in the Bai Sema style (Figure 3), which is heavily influenced by Thai-Buddhist engravings. Originating from India, the Bai Sema designs resemble the Kala-Makara design, which is commonly found in the entrances of temples in Thailand and India. This style may have reached Patani from Trowulan, Surabaya. In Patani, Bai Sema tombstones are very rare.

Fig. 3 Raja Ijau Bai Sema Tombstone (Bougas: Pg 39)

Queen of Patani “The Rainbow Queens”

Female Rulers in the Malay World

When James Brooke visited the Bugis state of Waco, Brooke observed that six out of the eight prominent chiefs were female (Brooke, 1848 I, 74-5). In Islamic Southeast Asia, the presence of female rulers appeared to be a common occurrence. Notably, female Muslim rulers were intricately connected to the realm of commercial trading. Throughout the 15th to 17th centuries, women in these regions played a significant role in engaging in trade activities. For instance, Pasai, the first Muslim state in Southeast Asia, had two queens during its prosperous trading era (1405-1434). Similarly, Japara in North Java emerged as a key naval and commercial hub under the rule of its female queen, Kali Nyamt, in the 16th century.

“Similarly, the women rulers of the diamond-exporting centre of Sukadana in Southwest Borneo (c. 1608-22), pepper-rich Jambi in East Sumatra (163~. 1655), and the sandalwood base of Solor, to the East of Flores (c. 1650-70), were on the throne during the brief period these states were important commercial centres.” (Reid, 2020, Pg 641)

In her research on “Ratu Acheh,” Sher Banu explored the lives of the four Queens of Acheh in the 17th century. The first queen, Sultanah Safiatuddin (1612-1675), took the throne following the death of her husband, Sultan Iskandar Muda. She was succeeded by her daughter, and four Acheh Queens ruled the kingdom for sixty years.

Similarly, a comparable scenario unfolded in Patani during the 16th and 17th centuries, with the kingdom being governed by four consecutive queens. Patani served as a significant trading post, particularly with China, during this period. The preference for female rulers stemmed from the cooperation of the Orang Kaya (male royal councillors and religious ulama) with the queens, recognising their adeptness as rulers with business acumen rather than because they were running out of males to inherit the thrones. During the reign of Raja Ijau:

“Patani the first queen has reigned very peaceably with her councillors … so that all the subjects consider her government better than that of the dead king. For all necessities are very cheap here now, whereas in the king’s time (so they say) they were dearer by half, because of the great exactions which then occurred.” (Van Neck, 1604:206)

Patani, under Raja Kuning, the Orang Kaya, paid less levies as Raja Kuning was a wealthy heiress and a capable businesswoman. The Orang Kaya saw how female rulers were more businesslike and profitable for themselves. They were also mild in ruling the states compared to male rulers.

Raja Ijau, the eldest daughter of Sultan Patik Siam, took power in Patani after the sudden deaths of many male family members. During her 32-year rule, Raja Ijau led an army against Pahang and defended Patani against Ayutthaya, fostering diplomatic relations and promoting culture and art. She is credited with the origins of the Mak Yong dance. Raja Biru continued her mother’s diplomatic legacy and was an adept mediator between the Dutch VOC and British EIC. Raja Ungu defied Siamese rule, aligning with Portugal, Pahang and Johor to repel a Siamese force and further solidify alliances through strategic marriages. Raja Kuning enhanced Patani’s economic prosperity and established it as a prosperous Malay trading post. Following her overthrow by a minister, she retired to Kuantan, Pahang, marking the end of female rule in Patani.

As outlined by Perret, the era of female rulers in Patani was characterised by a decrease in violent incidents and massacres within the royal families. This period was notably peaceful, fostering a sense of safety that encouraged traders to conduct business with relative security. However, following the reign of these queens, the Patani throne shifted to male lineages, possibly influenced by conservative factions aiming to enforce Islamic practices that restrict female leadership over men. The subsequent male rulers exhibited intense competition and a diminished focus on trade, leading to a decline in safety and profitability for Patani as a trading hub during their governance.

The Queens’ Title

Perret noted the Patani Queens used the Indian Sanskrit male title “raja” instead of the Islamic “sultanah” or the Malay “ratu.” Historical sources from Patani do not provide evidence of the title “Sultanah” being used. The discovery of a gold coin inscribed with the words “al-sultana-al muazam” (the great Sultanah) and “Khalada Mulkaha” (May God preserve her government) has led some to speculate that it may have been associated with one of the Patani Queens. Perret pointed out discrepancies between this coin’s inscription and those on coins issued by the Sultanah of Aceh, as well as the absence of coinage from the Queens of Sukadana and Jambi in the 17th century. He further questioned the authenticity of the claim that the Patani Queens ever adopted the Islamic title of Sultanah and pondered why there is a lack of mention in Malay sources regarding minted gold coins.

The Color Names

The Patani Queens were named after colours, and thus, the acronym ‘’Rainbow Queens of Patani’’ was coined by Teuuw and Wyatt. Some scholars likened it to how in Malay tradition, females were given names associated with colours, or that green is an Islamic colour, and Raja Kuning (yellow) had yellow skin and was given the colour yellow. Jocelin de Jong’s documentation in 1961 highlighted the prevalent use of colour names among Malays. For instance, titles like Tun Hitam or Tun Putih were commonly bestowed upon Malay women in Sejarah Melayu.

Professor Perret suggested that the tradition of using names based on colour could be rooted in religious or traditional beliefs associated with auspicious symbolism. For example, the Katika Lima system—where a day is divided into five periods, and each period is associated with a colour—is directly related to a Hindu god. Each colour represents the time of birth of the queen. A second possibility is that the colour was related to the day/time of birth, like the zodiac. It could also be related to Buddhist influence. In Buddhism, each cardinal points are related to a colour as also with the Chinese belief. It is also believed that names with colours are linked to the traditional culture of Chinese zodiac practises:

“The centre of the system is Vairocana, associated with the white colour, while interestingly, the colours of the four cardinal points correspond to the names of the four queens: North is associated with Amoghasiddi and the green colour; East is associated with Akṣobhya and the blue colour; West is associated with Amitābha and the red colour; South is associated with Ratnasaṃbhawa and the yellow colour. Moreover, the colours are associated with the same cardinal points in traditional Chinese culture.” (Damais 1969: 83-84: extracted from Perret’s article, 2022)

Perret also found through the sources that the use of colours for the queens was only used within the palace, and as for the foreigners, the queens were referred to merely as “old queen” or “young queen.” These colour names are definitely not by chance but linked with greatness for the royal household, or they were intentionally meant to legitimise the queen’s sovereignty in the state of Patani.

Power Sharing

Perret also noted the unique power-sharing practised by the four queens. The old queen is assisted by a young queen who acts as a regent and is the next in line. This power-sharing system seems to have worked for the Queens, as during their reigns, Patani flourished economically and politically.

Chronology of the Queens

Perret suggested that the dates of the Patani queens require further investigation since dates were never mentioned in Malay writings (namely Hikayat Patani, Sejarah Patani, Syair Patani and Kelantan). However, when various sources written in foreign records surfaced, this suggested that the periods or dates as deduced in Hikayat Patani were different and required re-examination. Some foreign sources cited Christian years while others utilised the Muslim calendar, and confusion emerged.

More confusion arose when understudying the Patani sources as the use of colours for the Queens was only for the internal royal court; thus, for foreigners, it’s either the Old Queen or Young Queen, as names of the queens were never cited in any foreign sources. It was quite a task to identify the period of rule of the Queens also because the Malay sources did not include dates/periods. However, a letter surfaced, the correspondence between one of the queens and the King of Portugal dated 31 March 1637. This threw new light into the confusion of the chronology of the queens. According to Perret, the dates of ruling for the queens require some rearrangement. Perret summed up these reigns as follows:

- Raja Ijau (Old Queen: r. 1584 – 28/08/1616; d. 28/08/1616)

- Raja Biru (Young Queen: r. ≤ 1601 – 28/08/1616; Old Queen: r. ca. 09/1616 – ca. 03/1636; d. ca. 03/1636)

- Raja Ungu (Young Queen: r. ≤ 1629 – 1634; d. between 1636 and 1638)

- Raja Kuning (Young Queen: r. end of 1634 or 01/1635 – ca. 03/1636; Old Queen: r. ca. 03/1636 – ≥ 1642; d. ≥ 1642)

Fig. 4 Chronology of Patani Rulers

Patani’s Emergence as a Trading Hub

Following Malacca’s fall to the Portuguese in 1511, Patani emerged as a lucrative alternative trading centre. It was also a strategic port for sailors travelling from China to Java to stop at Patani for shelter, repairs and trading. The region attracted a diverse array of merchants, including Chinese, Malay, Siamese, Persians, Indians, Arabs, Portuguese, Japanese, Dutch, and English traders. The peak of Patani’s trading significance is often associated with the reign of Raja Ijau. Chinese entrepreneurs played a pivotal role in Patani’s rise as they exchanged goods like porcelain, silk, and lacquer for cloves, nutmeg, sandalwood, and pepper sourced from the spice islands.

Historical records indicate that Patani’s influence as a trade hub extended beyond local waters. Patani junks engaged in trade with Banda for nutmeg and mace as early as 1526, while Chinese junks from Fujian frequented Southeast Asian ports like Pahang and Patani in the late 1520s. Indian traders also participated in the exchange, offering textiles in return for pepper, gold, and food items. Chinese and Indian goods brought to Patani were further distributed by Malay traders across Thailand and the Indonesian archipelago. Additionally, the Kingdom of Ryukyu served as a crucial intermediary linking China, Japan, and Patani, facilitating trade growth in the region.

“Like all major coastal trading places at the time in Southeast Asia, Patani was home to a cosmopolitan population. It is thus reasonable to suggest that some twenty languages were in daily or occasional use in Patani during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. (Perret, 2022: Pg 143)

However, Perret summarised that Patani’s position as a trading hub declined by the mid-17th century as trade restrictions limited the movement of Japanese traders and hindered Chinese-Japanese trade interactions. Furthermore, shifts in market demands led to a decreased interest in local spices like pepper and a decline in the popularity of Indian cotton materials. Patani struggled to adapt to changing trade dynamics during this period, failing to sustain its earlier prosperity and meet evolving commercial challenges.

Conclusion

Perret and Santos’ examination of foreign sources proved useful in shedding light on how Patani emerged as a significant state during the 16th and 17th centuries. These sources offered insights into the queens’ chronology, Patani’s administrative system, the layout of the old city, and its economic, political, and social structures during that era.

Determining the precise timeline of the queens proved challenging due to discrepancies in various historical texts. Foreign sources often referred to the queens generically as ‘old queen’ or ‘young queen’ and not by their names. Perret’s meticulous analysis allowed for the reorganisation of the queens’ chronology based on available manuscripts.

Once again, foreign sources are abundant and detailed in their description of the city’s location and design, but they are also confusing or, on many occasions, contradictory. Perhaps as suggested by Bougas, where only by excavation of the city/citadel location, artefacts excavated will provide evidence to support the history of Patani. The old city has never been excavated, nor have any archaeological methods been used to verify the sites and compare them with historical narratives.

The extent of real power wielded by the Patani Queens within the kingdom remains a subject of inquiry. Questions arise regarding whether the queens held substantive authority or if the influence lay with other figures like the Orang Kaya, councillors, Islamic leaders, Chinese merchants, or Javanese traders. While Malay sources like Hikayat Patani and Syair Patani remain silent on the queens’ authority, foreign accounts highlight their roles in trade management.

It is possible that the real power was with the court councillors, while the queens handled foreign traders. But then again, the four female rulers reigned for almost a century. It could not have lasted 100 years if it had not been for their skilful manoeuvring of the Orang Kaya and social-economic skills when dealing with foreign merchants.

Perret and the foreign sources may not have found the answers to establish the use of the queens’ titles. However, these sources are able to clarify many questions concerning the presence of female rulers in Patani. They can probably inspire the people of Patani today.

Fig. 5. Salt ponds, Ban Pa Re (D. Perret, June 1997)

References:

MV Focus Talk by Professor Daniel Perret on 27th May 2024, MV Room, JMM.

https://journals.openedition.org/archipel/2849 The Sultanate of Patani: Sixteenth-Seventeenth Centuries Domestic Issues by Daniel Perret

https://www.eksentrika.com/pattani-queen-southeast-asia-ratu-kuning/Legendary queens of Pattan

Teeuw, A. and David K. Wyatt, 1970. Hikayat Patani = The story of Patani. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, Pg 1-13.

https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=V_mPBAAAQBAJ&rdid=book-V_mPBAAAQBAJ&rdot=1Origin islam in Patani before Melaka (Pg 12)

https://www.academia.edu/35716822/Hikayat_Patani_pdf

Hikayat Patani Diselengara oleh Siti Hawa Hj Salleh, DBP, 2010

https://journals.openedition.org/archipel/2799 Patani and the Luso-Asian Networks (1516-1642)

Jorge Santos Alves , 2022

https://www.persee.fr/doc/arch_0044-8613_1990_num_39_1_2624. Wayne Bougas Patani in the early 17th century

https://angkordatabase.asia/publications/female-roles-in-pre-colonial-southeast-asia. ://about.jstor.org/terms

Modem Asian Studies 22, 3 (1988), pp. 62!r645. Printed in Great Britain. Female Roles in Pre-colonial Southeast Asia ANTHONY REID

https://k4ds.psu.ac.th/ebook/pdf/b002.pdf Wayne Bougas “Islamic cemeteries in Patani” 1988 (pg 28-48)

Sher Banu A.L. Khan, Sovereign Women in a Muslim World, NUS Press, 2017

(2007) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233132109_Some_reflections_on_ancient_Islamic_tombstones_known_as_Batu_Aceh_in_the_Malay_world.Some reflections on ancient Islamic tombstones known as Batu Aceh in the Malay world: Daniel Perret