by Ong Li Ling

I recently attended a curatorial tour of Mahen Bala’s Ceb Bah Heb Elders of Our Forest exhibition at the Taman Tugu Nursery Trail. This exhibition is part of a documentary looking at the life of Batek people. The exhibition is on until the 21st of July; do go check it out. The documentary itself looks at the relationship between the forest and its people. You can find more details on the documentary here.

Below is an aerial photograph of Sungai Tembeling. At present, the left hand side of the river is still properly preserved. Unfortunately, the right side has been exploited. If you only live in the jungle, you will never see land this way. The Batek do not see land the way Google Maps, Waze and city folk see land. The Batek use trees and mountains as markers. The coloured structures in the photograph are Batek settlements.

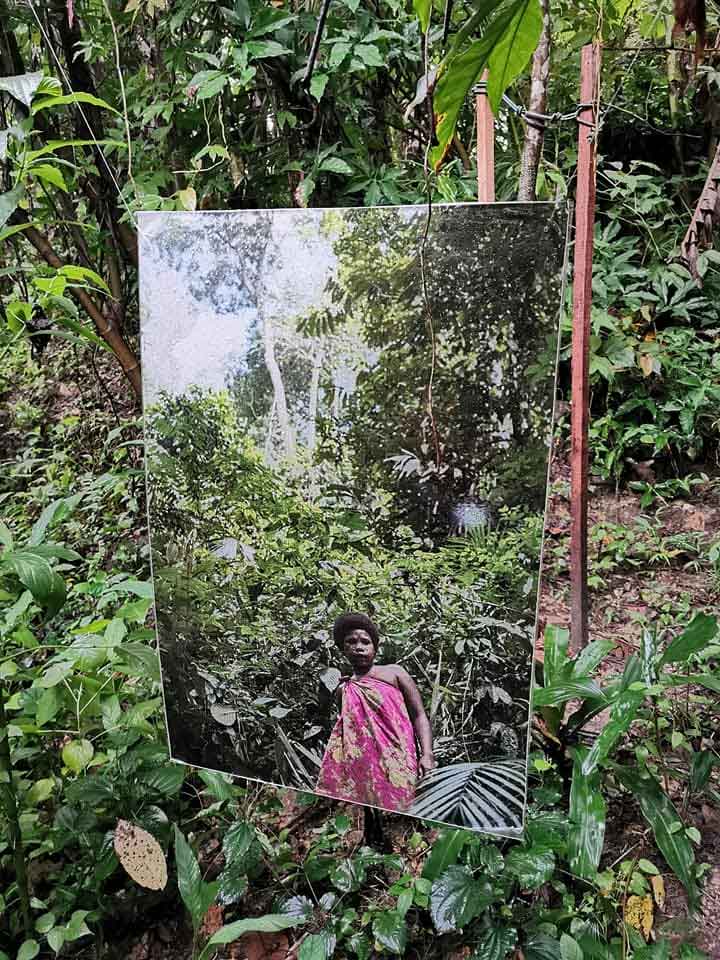

Traditionally the Batek are nomadic and hence they had no proper settlements. Due to pressures from outside and their inability to continue living off the forest, they are changing their lifestyles. Our government is telling them to stay put in order to participate in the lucrative eco-tourism business. This is against their ancestral practice as they are used to travelling and foraging. This photograph shows what the typical Batek person does all day. They are waiting for tourists to pop over so that the curious tourist can take photos with them. Reminds me of the Long Neck women I saw in Myanmar. The tour guides will give them a token amount to “add to the authenticity” of the jungle tour. This shows how hard it is for the Batek people to live off the forest today.

The Batek only take what they need from the forest. Whatever they hunt or forage will be brought back to the village to be shared. They have respect for the animals they kill. They believe bad luck will befall them if they break the taboos.

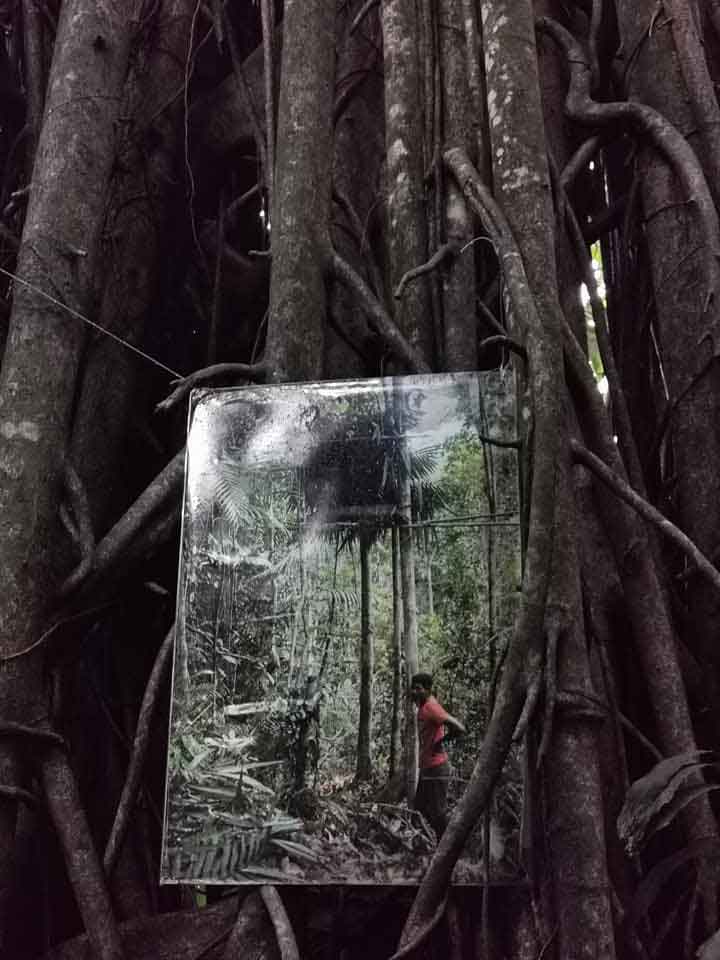

This photograph shows a typical Batek family and the structures they build. This structure is called a Hayak, Lintus or Lean To. Once they decide where to spend the night, the whole family is involved in setting up their home for the night. When they are ready to move, the shelter is returned to the forest and so their impact on the jungle is minimized. The Batek view the seasons differently than we do. During the fruiting season, they live entirely on fruits. During the flower season, they survive by harvesting honey.

The children are involved with the running of the community from a young age. As soon as they are able, they learn survival skills such as how to use the parang and how to weave batik. This period is also an important time for bonding, as the elders will tell the children folk tales. The children are taught that every member of the family is important.

This is a photograph of Mr Di. He is holding a blowpipe and he carries a canister of darts around his neck. The blowpipe is an important asset to the Batek and they keep their blowpipe from cradle to grave. It is the most important of their material possessions. Batek people are egalitarian in that they consider both genders as equals. Women can also hunt and forage food and men can take care of children. This equal partnership relationship is now changing as they are forced to stay in one place and men are forced to do work requiring hard labour. Hence, the women stay at home to look after their kids. We can see the damage that this has done to their community. Modern civilisation is forcing our ideas and our “modern” ways of life on them and they have no other choice but to follow.

This is a photograph of Mr Di’s son. In general, the Orang Asli are depicted negatively in the media. We often see them when there is negative news e.g. protest against deforestation. The way these articles are written are so negative towards the Orang Asli that many think that “they have not caught up with our modern world”. Mahen made sure that his photographs show that the Batek as dignified and empowered. Some Orang Asli groups have traditional costumes and they wear these with pride. However, they have been directed to wear the costumes for the sake of tourism and that is not a good practice. Just in case you are wondering, the Batek do not have a traditional costume.

This is an important photograph as it shows the burial site of a deceased Batek. They will choose the highest tree that they can climb and they will build a simple structure. They will then start a fire to keep animals away. The Batek believe that the soul will fly to heaven. This location is kept a secret, as they do not want outside disturbance. It was reported in the news recently that the Kelantan government exhumed the body of a Batek, did a post mortem and then buried the body according to Islamic rites!

The Batek gather and share stories whilst hunting e.g., “I saw a herd of elephants next to the river”. This allows them to form a shared mental map of the area. They have a ground view of the land and whenever people share stories, they can imagine what else is happening on their land. The Batek use trees that really stand out as waypoints to navigate the terrain.

This photograph shows some Orang Asli children going to school. Most of them have trouble getting to school due to transportation. Some Orang Asli kids travel 12 hours per day to receive an education and so it takes amazing determination and grit. The cost is another challenge, as their parents cannot afford shoes and uniforms. They are sometimes discriminated against by teachers and hence they do not find school enjoyable. After a while, they feel so discouraged they prefer to stay at home and help their parents. Mahen met many bright Batek kids. Some quit school before the age of 14 due to these challenges. The statistics show that out of 100 who attend primary school, only six are expected to finish Form 5.

This photograph shows the Orang Asli children happily bathing in the river. Most of us will find it difficult to swim in these rivers due to the currents.

This final photograph depicts Mr Di against the backdrop of construction and development. It encourages us to reflect on the Batek way of life versus our way of life. We can still live as Malaysians and go back home and practise our traditional way of life. So why is it that we force Batek people to change and adapt to our way of life? According to the statistics, there are only 1500 Batek people left. It is only fair that we acknowledge their customary rights to their land. The Batek are well versed in the medicinal values of forest plants but if you are a researcher, it may not be in the Batek people’s best interest to publish these secrets in journals. We can assume that greedy pharmaceutical companies will come and grab the knowledge and then patent this knowledge for their commercial benefit. When that happens, there is little else left for the Batek to survive on.