by Maganjeet Kaur

The Kedah Tua International Conference (KTIC) in Sungai Petani kick-started on 21 May 2016 with Dr Stephen Oppenheimer presenting the first keynote address. His presentation focused on using genetic phylogeography to trace the migration patterns in South East Asia. Two pieces of DNA are used to build a gene network: mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) which is passed from mother to daughter and Y-chromosome (NRY) which is passed down the male line. As these two pieces of DNA do not recombine during reproduction, they are transmitted unchanged through the generations allowing scientists to trace human migrations through random mutations that occur in these DNA strands.

The Kedah Tua International Conference (KTIC) in Sungai Petani kick-started on 21 May 2016 with Dr Stephen Oppenheimer presenting the first keynote address. His presentation focused on using genetic phylogeography to trace the migration patterns in South East Asia. Two pieces of DNA are used to build a gene network: mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) which is passed from mother to daughter and Y-chromosome (NRY) which is passed down the male line. As these two pieces of DNA do not recombine during reproduction, they are transmitted unchanged through the generations allowing scientists to trace human migrations through random mutations that occur in these DNA strands.

A large part of Dr Oppenheimer’s presentation centred on a recently published paper that used genetic methods to study the ancestry of inhabitants in island South East Asia (ISEA). For the past 30 years, the Out of Taiwan theory has held sway to explain these origins. This theory is based primarily on linguistic evidence; the antecedents of Austronesian languages spoken in ISEA can be traced to the aboriginal population of Taiwan. By extension, Southern China is theorised as their original homeland. The Austronesian speaking population is said to have arrived in Taiwan from Southern China around 6500 ya. From Taiwan, they moved into the Philippines around 5000 ya and reached southern Philippines by 4000 ya. From here, there was rapid dispersal to the rest of ISEA and Oceania with arrival in the Pacific by 3000 ya.

A model that combines this Holocene colonisation with an earlier Pleistocene colonisation from Southern China via the mainland has successfully withstood attacks from detractors who favour a homeland from within the Sunda shelf. The Out of Sunda theory proposes that the inhabitants of ISEA originated from within ISEA itself and that it was the sinking of the Sunda platform which provided the impetus for dispersal. This turns things around and places insular South East Asians as ancestors of the aboriginal Taiwanese. Genetic evidence has been employed by scientists on both sides of the divide to support their views. The recent study conducted by a group of international scientists, of which Dr. Stephen Oppenheimer was a part, is the most comprehensive undertaken to date. It uses a combination of mtDNA, NRY, and published genome-wide data. The results are surprising in that while they mostly support the Out of Sunda theory, the study also detected minor migrations during the Late Holocene from Taiwan, corresponding to the Out of Taiwan time-frame. However, the study noted that these migrations did not have much influence on the ISEA gene pool and that the impact was mostly cultural and linguistic.

The story of human migration starts around 85 000 ya in East Africa when a group of Homo sapiens (modern humans) crossed the Red Sea into the Arabian Peninsula and then travelled along its coastline into the Indian subcontinent. All humans outside Africa are descended from this single exit. These beach-combers continued around the Indian Ocean coast to arrive at Lenggong Valley in the Malayan Peninsula by at least 74 000 ya. They then traversed the edge of the Sunda platform before moving north into Indo China and Southern China as well as south into Australia. It should be noted that an earlier migration out of Africa arriving at the Levant around 125 000 ya failed to populate the world as the onset of an ice-age either killed the population or forced them back into Africa.

The diagram above shows clusters of gene types (mtDNA). The green circles represent gene types in Africa and the large circle on the right shows gene types in the rest of the world. The single exit out of Africa is represented by the haplogroup L3 which gave rise to two important branches outside Africa. The M branch evolved in present day India and is found in all humans outside Africa except Europeans and Levantines. The N branch evolved around present day Pakistan/Iran and is found in all humans outside Africa including Europeans and Levantines. The M supergroup gave rise to M9 which evolved in SEA around 50 000 ya. M9, in turn, gave rise to the haplogroup E which developed in Sundaland around 23 000 ya. This haplotype is widely dispersed and some of its daughters can be found in Taiwan; 15% of all gene lines in ISEA and Taiwan belong to haplogroup E.

One of the main reasons behind the wide dispersal of haplogroup E was the sinking of the Sunda platform caused by three rapid rises in sea levels between 15 000 and 7000 ya. The effects of these sea level rises can be seen in the genetic record – genetic drift, equivalent to extinction, corresponds to the three distinct rises in sea levels. The extinctions were followed by a major expansion of haplogroup E which expanded throughout ISEA, as far north as Taiwan, and east of Guinea. As the land halved and the coastline doubled, the population adapted itself to maritime activities allowing them to carry their genes far and wide.

The Austronesian migration can be seen through mtDNA haplotype M7c3c. It has a similar distribution as E but goes in the opposite direction. Coming from China into Taiwan, it spread from Taiwan into SEA around 4000 ya. This haplotype is present in around 8% of Indonesians.

The diagram above shows that, along the route out of Africa, Sundaland has the highest number of founding branches, 30 in total, making it the most diverse place outside Africa. If we look at the indigenous populations of the Malayan Peninsula, 86% of their lineages come from locally founding Sunda lineages and 14% from East Asian lineages. For the Malay population, around 58% of their lineage is from local Sunda founding lineages, 38% from East Asia, and 4% from South Asia. Of the local Sunda lineages, 33% of these lineages go back 60 000 – 25 000 ya. Of the East Asia lineages, only 7% are from Taiwan.

The Malayan Peninsula not only facilitated movements from Indo China and East Asia to ISEA (the spread from Indo-China to ISEA associated with Hoabinhian culture is about 20 000 ya), it also facilitated movements from Africa to Indo China, East Asia, and Australia.

Archaeological evidence supports the assertion that Lenggong Valley was a key area on the migration path of humans. Kota Tampan in Lenggong Valley has yielded a stone tool making workshop covered in ash from the volcanic eruption that created Lake Toba in Sumatra. This ash dates to 74 000 ya attesting that modern humans must have arrived in Lenggong Valley before this eruption took place. The Lenggong Valley has also shown continuous settlement from 40 000 ya to present. The finding of a stone hand-axe dated to 1.83 million ya at Bukit Bunuh, about 1 km away from Kota Tampan, shows that Lenggong was also on the migration path for Homo erectus, an earlier species of the Homo genus. This hand-axe was found buried in suevite. Its discovery puts Lenggong Valley on the migration path of Homo erectus, whose best known representatives are the Java Man (700 000 years old) and Peking Man (500 000 – 300 000 years old).

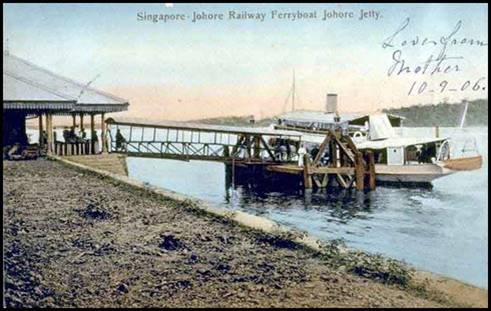

railways in Malaya was not a simple task. Whilst the British planned a substantial network, the jungle was often unexplored and was often a major barrier to travel. Significant difficulties were frequently encountered during surveying, constructing and subsequently in maintaining the railway system.

railways in Malaya was not a simple task. Whilst the British planned a substantial network, the jungle was often unexplored and was often a major barrier to travel. Significant difficulties were frequently encountered during surveying, constructing and subsequently in maintaining the railway system.

Image credit: Maganjeet Kaur

Image credit: Maganjeet Kaur