By Manjeet Dhillon

Celebrating the Harvest

Sabah’s annual harvest festival, Tadau Kaamatan, is a celebration deeply rooted in the Kadazandusun community’s cultural heritage. Centred around the rice harvest, the month-long event features rituals, traditions, and myths that highlight the grain’s significance. These myths, though diverse in origin, often share a unifying theme: the sacrifice of a beloved female relative.

Historically and traditionally, Kaamatan was held at the first sighting of the full moon following the harvesting season. This period, known as “tawang” (literally meaning “full moon”), signified the perfect timing for the festival. The month-long celebration culminates on May 30th and 31st, highlighting the profound significance of rice for the indigenous communities of Sabah.

Credit: Sabah Tourism / Tsen Lip Kai

Rooted in Legend

The roots of Kaamatan stretch back centuries, intertwined with the Kadazan legend of Huminodun. This tale tells of a time when harmony reigned between a benevolent god, Kinoingan, and his people on earth. However, Kinoingan’s son, Ponompulan, disrupted this peace, leading to his banishment to Kolungkud, or the underworld, and a series of devastating plagues upon humanity.

Credit: Sunduan Do Huminodun (The Spirit of Huminodun) by Pangrok Sulap

Faced with drought and famine, Huminodun, Kinoingan’s daughter, made the ultimate sacrifice, she offered her own body to nourish the people. Through Huminodun’s sacrifice, her body transformed into various food sources: rice from her flesh, coconuts from her head, tapioca from her bones, ginger from her toes, maize from her teeth, and yams from her knees. and a variety of other edible plants sprang forth, ensuring the community’s survival.

This bountiful harvest marked a turning point, and Kaamatan became an annual celebration to honour Huminodun’s sacrifice and express gratitude for the blessings of the land.

While the details differ, a similar theme of sacrifice for the community’s well-being emerges in the Murut (tagal) genesis myth of siblings, Olomor and Sulia. In this narrative, Olomor sacrifices his sister Sulia, following a vision during their rice field clearing. Seven days later, various plants sprout, including rice, highlighting the theme of sacrifice for the community’s well-being.

(While the details differ, a similar theme of sacrifice for the community’s well-being emerges in the Murut (Tagal) genesis myth of siblings, Olomor and Sulia. In this narrative, Olomor sacrifices his sister for the same purpose. As the story goes, Olomor and Sulia were clearing land to cultivate rice. Later that day, while resting, Olomor had a vision in which he saw Sulia being sacrificed to produce rice seedlings. Despite his guilt, he felt compelled to follow through with the vision. He brought Sulia to the clearing and killed her. Her body rolled on the ground, and her blood flowed to every corner of the cleared land. Seven days later, Olomor returned to find that various plants had sprouted, one of which was rice.)

Both Kadazan and Murut legends tell of sacrifices made for the community’s well-being. These stories highlight the deep respect these cultures have for the land and the rice harvest it provides.

A Journey of Rituals

The heart of Tadau Kaamatan unfolds through a series of rituals performed by the Bobohizan, a traditional priest or priestess. The six distinct rituals described below are typical of the Kadazandusun community of the “tangara” in the Penampang-Papar area.

- Kumogos: Before harvest, a Bobohizan (priest/priestess) chooses the seven best rice stalks. These are left scattered in the field to appease any spirits and promise an offering after harvest.

- Kumotob: Following Kumogos, the Bobohizan selects the best unharvested rice stalks. These are tied together and stored in a tadang (rice basket) for next season’s planting.

- Posisip: The Bobohizan carries seven tied rice stalks to the rice hut and inserts them into a bamboo pole kept in the tangkob (container) while chanting prayers for Bambaazon, the rice spirit, to stay and bless the harvest.

- Poiib: the Bobohizan carefully pours rice into the tangkob within the hut. This continues until all the rice is transferred, accompanied by chants beseeching the rice spirits to watch over the stored harvest.

- Magavau: The most significant ceremony, Magavau restores Bambaazon’s spirit and offers food as a gesture of respect.

- Humabot: This final stage explodes with joyous celebrations, featuring traditional dances, sports competitions, and the crowning of the Unduk Ngadau, a maiden who embodies the spirit of Huminodun.

Credit: https://mpu2015kadazandusun.blogspot.com/

Credit: The Borneo Post

A Look at Specific Traditions

The Kadazandusun are not alone in celebrating this bountiful season. There are other indigenous communities that have each developed unique traditions to express gratitude for a bountiful crop and appease the spirits who ensure their success.

The names for the harvest festival vary across ethnicities. The Rungus call it “kokotual” and the Timugon Murut celebrate “orou napangaan nanantab.” While the festival’s core message of gratitude remains constant, the names and traditions vary across ethnicities. The Lotud Dusun of Tuaran focuses on intimate rituals with animal sacrifices and symbolic dances, while the Timugon Murut of Tenom holds a communal feast with “mansisia” celebrations. The Tagal Murut holds a lively seven-day celebration with activities like cockfighting and dancing. Meanwhile, The Rungus of Kudat perform rituals involving animal sacrifices and a “mongigol sumundai” dance throughout the night. Despite these ethnic variations, all celebrations share a common thread of thanksgiving and respect for the land.

A Celebration of Community

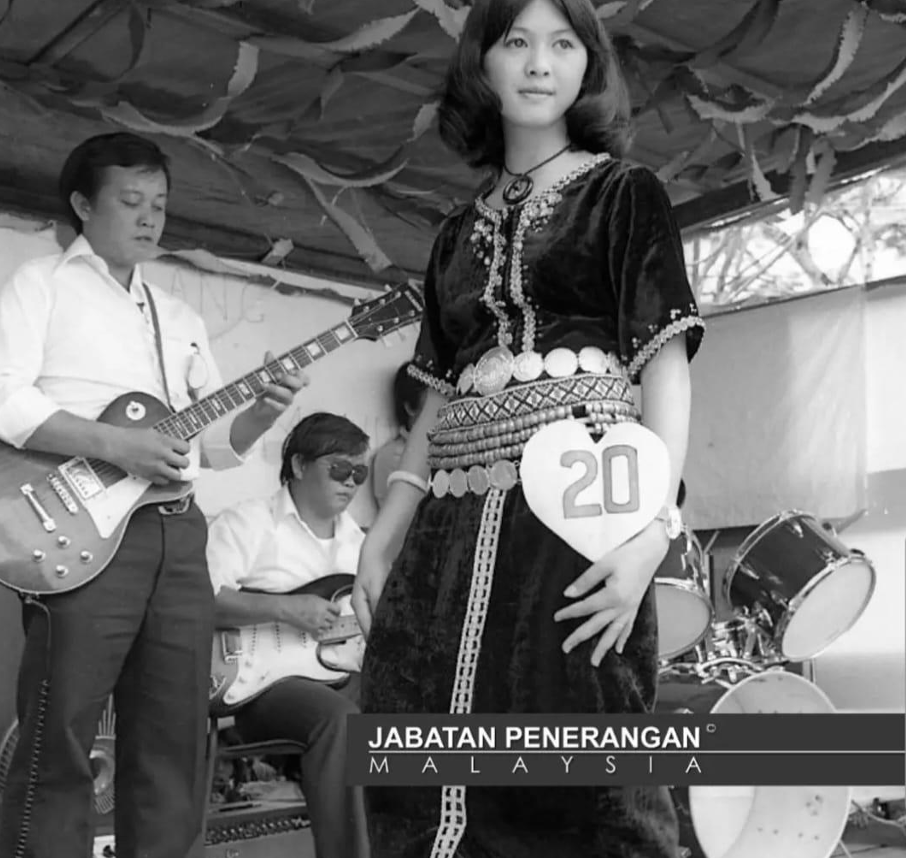

As Tadau Kaamatan reaches its peak, the Unduk Ngadau pageant takes centre stage. Held on May 31st, contestants from various districts embody the spirit and grace of Huminodun, the mythical figure who sacrificed herself for the harvest. Through their elegance and cultural knowledge, they compete to be crowned the Unduk Ngadau, literally meaning “the sun at its zenith—the brightest point of the day” in Kadazandusun.

While the Unduk Ngadau pageant captures the spotlight, Kaamatan also celebrates the rich musical heritage of the Kadazandusun people through a vibrant singing competition known as Sugandoi. The Sugandoi competition features age-group categories, ensuring traditional music resonates across generations.

Credit : Jabatan Penerangan Sabah

Fun Fact: The Spirit Behind the Song: Did you know Sugandoi has a fascinating history? For the KadazanDusun community, Sugandoi was once a “spirit” invoked by the Bobohizan (priestess) and housed in a large jar called a “Kakanan” by the Kadazan Tangaah tribe. This spirit was believed to watch over families and bring good fortune through a ceremony called “Moginakan.” During this ritual, the Bobohizan would chant incantations called “Monugandoi,” which praised the creator (Kinoingan) and the spirit of Sugandoi. These chants laid the foundation for the modern Sugandoi singing competition. No wonder the name stuck!

Adding to the atmosphere are traditional games and competitions. From displays of strength in arm wrestling (mipulos) and knuckle wrestling (mipadsa) to showcasing skills in blow piping (monopuk) and catapulting (momolositik), these games provide a fun and interactive way to experience Kadazan Dusun culture. Teamwork is tested in tug-of-war (migayat lukug), while balance and agility are on display during bamboo stilt walking (rampanau).

Credit: https://makangang2015.blogspot.com/

A Feast for the Senses

No festival is complete without a feast for the senses, and Tadau Kaamatan doesn’t disappoint. From the tangy zing of Hinava (raw fish) to the textures of Butod (sago grubs), the flavours of Pinasakan (braised fish), the tart tang of ambangan (wild mango), and the earthy warmth of Tuhau (wild ginger), Tadau Kaamatan is a feast for the senses. Lihing, a rice wine made from fermented rice and stored in clay jars, adds a special touch to the celebratory spirit.

Credit: https://borneonews.net/

A Legacy Endures

Tadau Kaamatan is more than just a harvest festival; it’s a cornerstone of Kadazandusun identity and other ethnicities in Sabah. These age-old traditions, a vital link to the past, ensure their shared cultural heritage continues to thrive for generations to come. It’s a celebration of the land, its bounty, and the enduring spirit of these communities.

References

- Kaamatan Special: The Rituals of Tadau Kaamatan (Harvest Festival) from http://www.e-borneo.com/insideborneo/leisure0205.shtml

- Huminodun: The Mystical Origin of the Kadazandusun People from https://www.flyingdusun.com/004_Features/010_Kaamatan02.htm

- Sabah’s Culture (Harvest Festival) from https://sourcesofknowledge.wordpress.com/2013/06/02/sabahs-culture-harvest-festival/

- Keningau, The Guide from https://pubhtml5.com/xvgw/junm/Keningau_The_Guide_2023/18

- Apa It Sugandoi from http://www.sentiasapanas.com/2019/05/sejarah-sugandoi.html#ixzz7UwYVDatb

- The Anthropological Profile of the Kadazandusuns of Borneo: The Kaamatan Rituals compiled by Allan G Dumbong from https://wayaantokou.blogspot.com/2005/12/

- Who is Huminodun?. Sumandak. Sino. Kadazan from http://borneobonita.blogspot.com/2017/01/who-is-huminodun.html

- Barlocco F., 2011. A Tale of Two Celebrations: The Pesta Kaamatan as a Site of Struggle between a Minority and the State in Sabah, East Malaysia. Asian Journal of Social Science from https://www.jstor.org/stable/43497845?seq=1

- Dusunology from https://www.facebook.com/sundayak777northborneo

- Kaamatan highlights spirit of peace and friendship this season by By Mariah Doksil from https://www.pressreader.com/malaysia/the-borneo-post/20160514/282411283538614

- The Encyclopedia of Malaysia: Peoples and Traditions