by Goh Yoke Tong

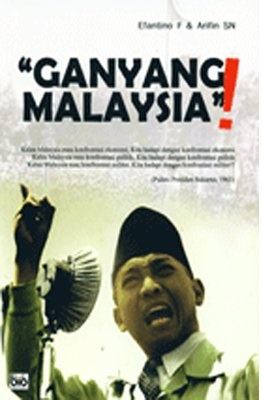

The Indonesian-Malaysian or Borneo confrontation was an undeclared war, from 1962 to 1966, that stemmed from Indonesia’s opposition to the formation of Malaysia. The term ‘Confrontation’ was coined by Indonesia’s Foreign Minister, Dr Subandrio, in January 1963, and has come to refer to Indonesia’s efforts to destabilise the new federation, with a view to breaking it up. The conflict resulted from Indonesia’s President Sukarno’s belief that Malaysia, which became official on 16 September 1963, represented a British attempt to maintain colonial rule behind the cloak of independence granted to its former colonial possessions in the South East Asian region.

In the late 1950s, the British Government had begun to re-evaluate its force commitment in the Far East. As part of its withdrawal from its South East Asian colonies, Britain moved to combine its colonies in Borneo with the Federation of Malaya (which had become independent from Britain in 1957) and Singapore (which had become self-governing in 1959). In May 1961, the British and Malayan governments proposed a larger federation called Malaysia, encompassing the states of Malaya, Sabah, Sarawak, Brunei and Singapore.

By the close of 1962, Indonesia had achieved a considerable diplomatic victory, which possibly emboldened its self-perception as a notable regional power and thus its ability to extend its dominance over its weaker neighbours in the region. It was in the context of Indonesia’s success in the Netherlands’ West New Guinea dispute that Indonesia cast its attention to the British proposal for the formation Malaysia. Opposition to Malaysia also favoured Sukarno politically by distracting the minds of the Indonesian public from the appalling realities at home as evidenced by gross mismanagement, nationalistic policies that alienated foreign investors and rife corruption. Everyone in Indonesia felt the hardships of high inflation and food shortage. Sukarno also had dreamed of an Indonesia that was like the glorious ancient Srivijaya and Majapahit empires.

Sukarno argued that Malaysia was a British puppet state, a neo-colonial experiment contrary to that of revolutionary Indonesia, and that the creation of Malaysia would perpetuate British control rather than ending its colonial domination over the region. He argued that this had serious implications for Indonesia’s national security as a sovereign nation especially in light of the fact that Britain would continue to have military bases in Malaya, Sabah, Sarawak, Brunei and Singapore, which are a stone’s throw away from Indonesia’s backyard.

Similarly, Philippines made a claim to North Borneo or Sabah, arguing that they had been historically linked through the Sulu Sultanate. Manila maintained that the area was once owned by the Sultan of Sulu, and because Sulu is now part of modern Philippines, that area should therefore belong to Philippines through the principle of extension. While Philippines, under President Macapagal, did not engage in armed hostilities with Malaysia unlike Indonesia, diplomatic relation was severed after the former deferred in recognising the latter as the successor nation of Malaya.

As for Brunei, Sultan Omar was undecided on whether he would support joining Malaysia because of the implied reduction of his influence as the head of state and significant amounts of Brunei’s oil revenue being diverted to the federal government in Kuala Lumpur to be shared among the proposed states of Malaysia. Brunei was to be the tenth state of Malaysia, whose sultan would be eligible to be the king of the country on a rotational basis for a five-year tenure and the sultans of Malaya had made it clear that he would have to wait his turn. This did not go down well with him as he could not foresee the prestige of being a king in his lifetime due to his place in line. Furthermore, AM Azahari, a Brunei politician and veteran of Indonesia’s independence movement who was against colonial rule, also opposed joining Malaysia on similar grounds as Indonesia.

In December 1962, Brunei faced a revolt by the North Kalimantan National Army (NKNA), which was backed by Indonesia and was pushing for Brunei’s independence instead of it joining Malaysia. In response to the revolt, the British and other Commonwealth troops were sent from Singapore to Brunei, where they crushed the revolt within days by securing Brunei’s capital and ensured the Sultan’s safety. The insurrection was an abject failure because the poorly trained and ill-equipped guerillas were unable to seize key objectives such as capturing the sultan of Brunei, seize the Brunei oil fields or take any British hostages.

Following NKNA’s military setback in Brunei, small parties of armed insurgents began infiltrating Malaysian territory along the Indonesian border in Borneo on sabotage and propaganda missions. The first recorded incursion of Indonesian troops was in April 1963 when a police station in Tebedu, Sarawak was attacked. After the formation of Malaysia in September 1963, Indonesia declared the ‘Crush Malaysia’ campaign leading to the escalation of cross border incursions into Sabah and Sarawak, which had then ceased to be British territories. Indonesia also began raids in the Malaysian Peninsula and Singapore in 1964. To repulse the infiltrators and prevent their incursions, the British and other Commonwealth troops remained at the request of Malaysia. Together with the Malaysian troops, they engaged in successful offensives against the Indonesian troops.

The intensity of the conflict began to subside following the events of the ‘30 September Movement’ and General Suharto’s rise to power in Indonesia. On the night of 30 September 1965, an attempted coup by the Indonesian Communist Party took place in Jakarta, which was successfully put down by Suharto. In the ensuing confusion, Sukarno agreed to allow Suharto to assume emergency command and control of Jakarta. The train of events that were set off by the failed coup led to Suharto’s power consolidation and Sukarno’s marginalisation, who was placed under house arrest soon after the transfer of power was completed. Peace negotiations were initiated during May 1966 before an agreement was ratified in August 1966 with Indonesia recognising Malaysia and officially ending the conflict. In March 1967, Suharto was able to form a new government in Indonesia that excluded Sukarno.

REFERENCES:

- Genesis of Konfrontasi : Malaysia, Brunei & Indonesia 1945 to 1965 – Greg Poulgrain (1998)

- Crossroads : A Popular History of Malaysia & Singapore – Jim Baker (2014)

- Chronicle of Malaysia – Philip Mathews (2007)