by Sarjit Kaur

Introduction

On Saturday 21 December 2024, 30 Museum Volunteers were treated to an educational guided tour of the Malay World Ethnology Museum (MEDM), situated above the Orang Asli Craft Museum and within the vicinity of the National Museum. This museum was officially opened to the public in March 2002 and fun fact, it occupies the first floor of a former Japanese Restaurant, Fima Rantei.

The idea for MEDM was mooted by the first Director General of Museums Malaysia, the late Dato’ Shahrum Yub, following a resolution at the 1989 Malay Civilisation Convention. The architecture of this building is similar to the National Museum. The museum provides visitors with a deeper understanding of Malay arts and culture.

Museum Scope

While the scope of the Malay world encompasses the Nusantara or Malay Archipelago, the MEDM focuses on Malay arts and culture in Malaysia. It:

- builds upon and expands the content in Gallery B of the National Museum, offering a detailed exploration of the Malay world artefacts and unique traditions by state.

- features and interprets the crafts and traditions depicted on the National Museum’s external West Mural on Malayan Crafts and Craftsmen.

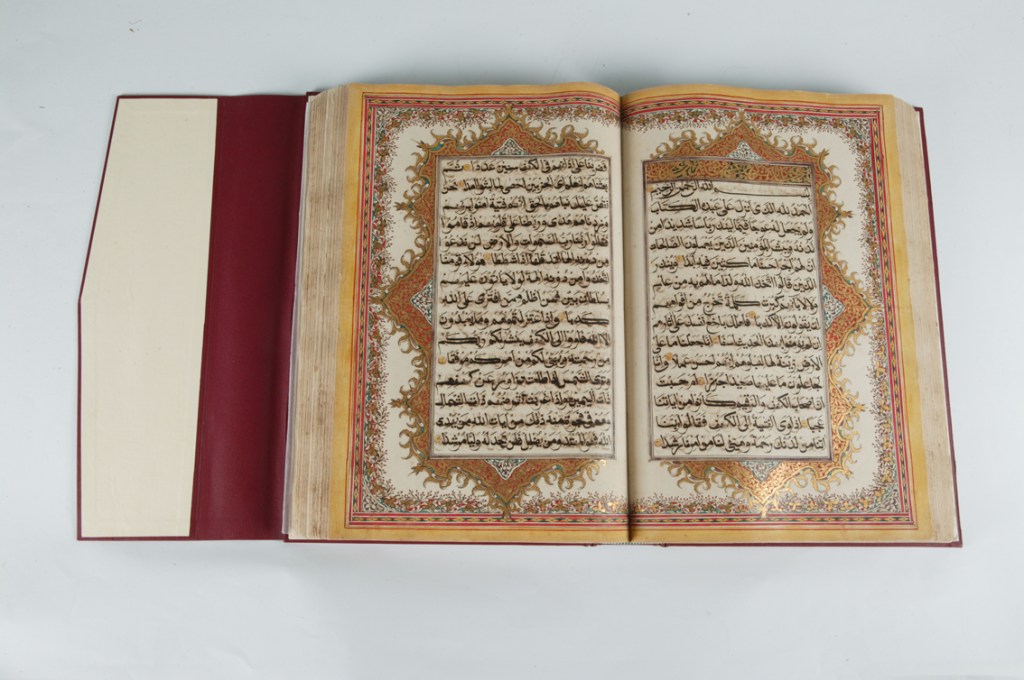

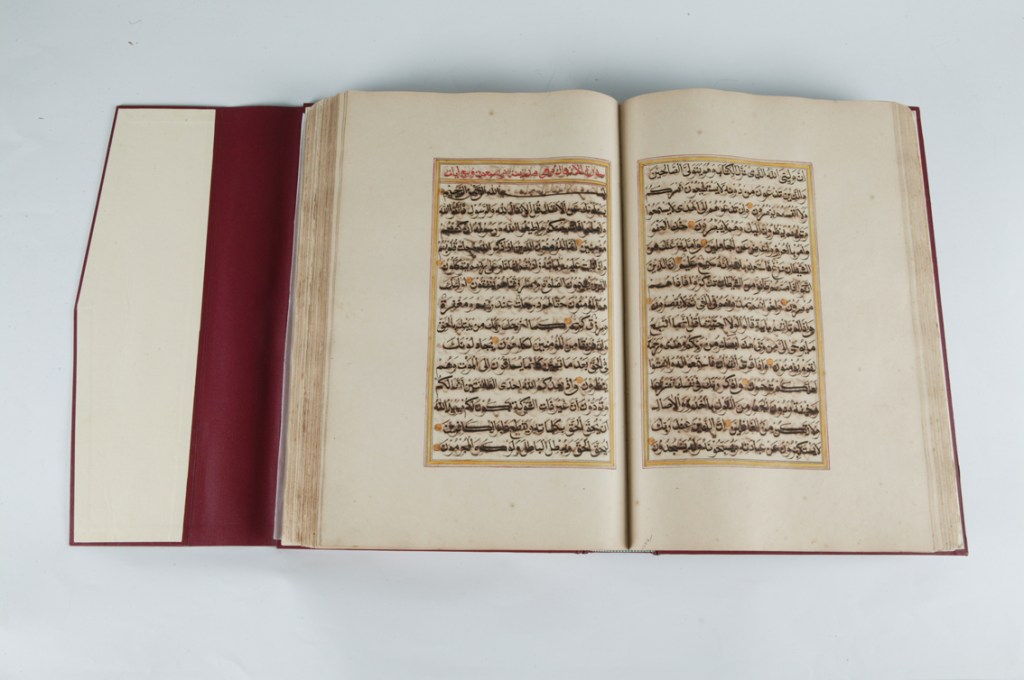

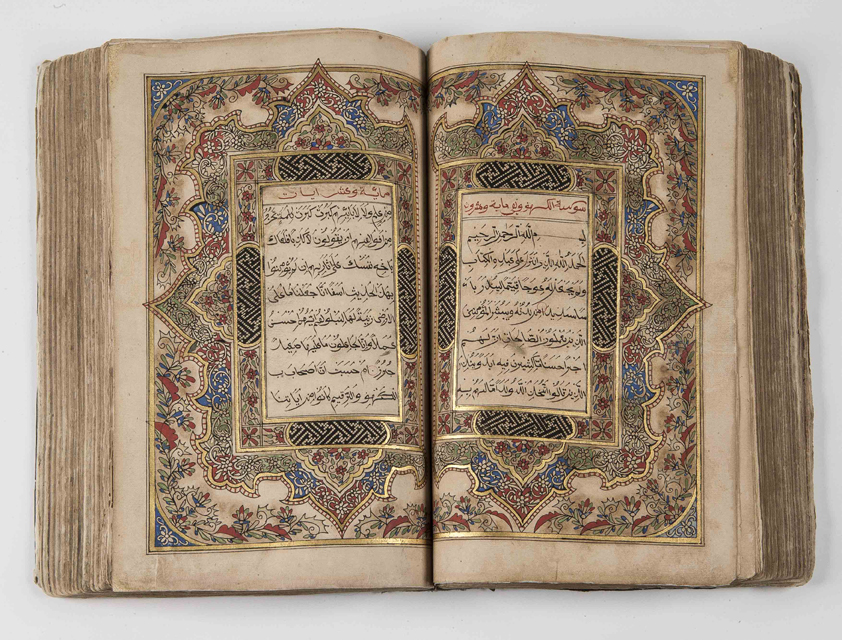

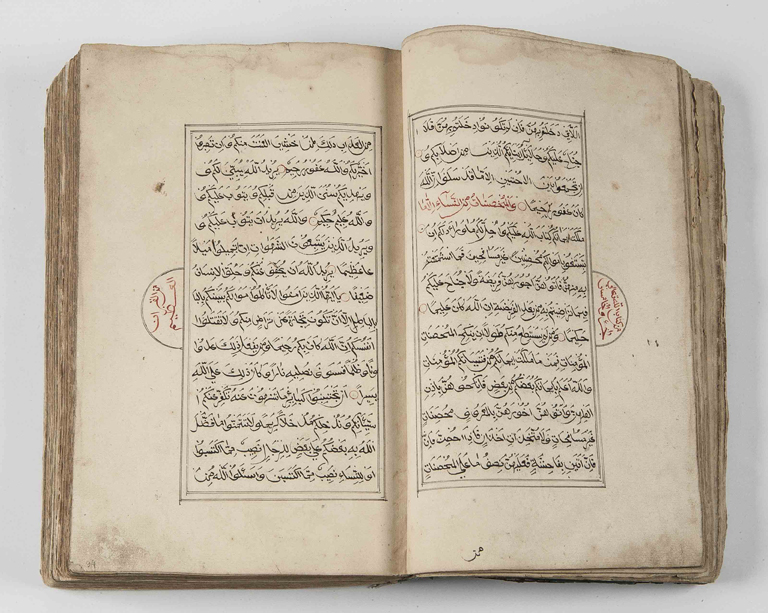

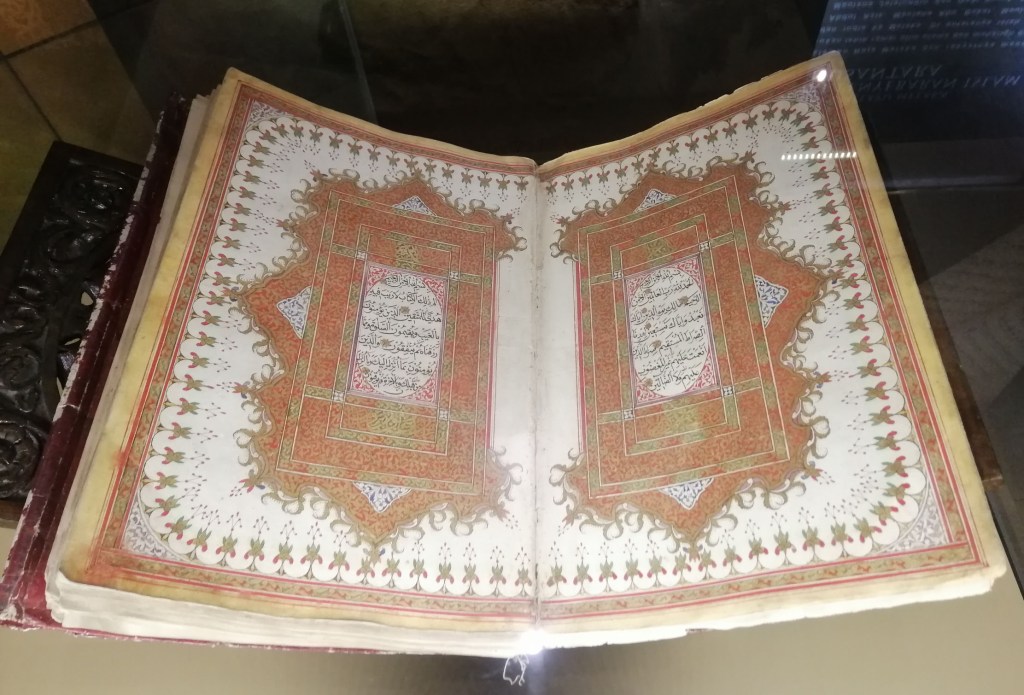

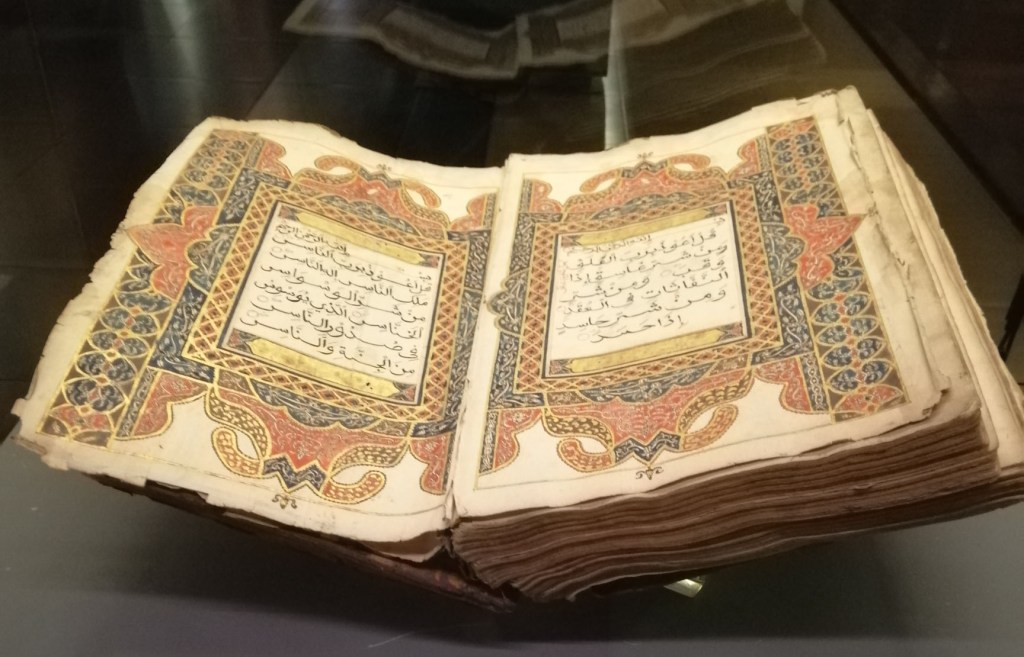

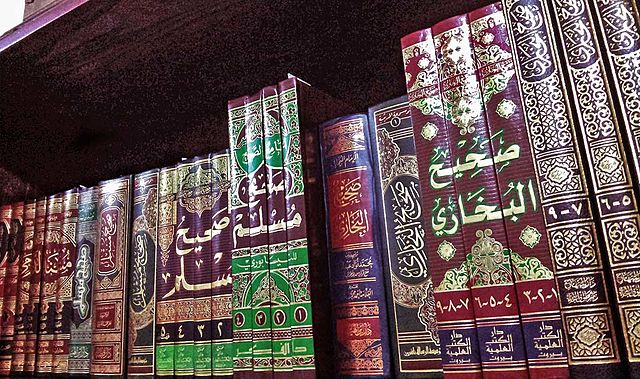

- reflects the evolution of the belief systems and practices in the Malay world, transitioning from animism to Hindu-Buddhist influences and finally to Islam, as seen in the essence of the exhibits, its iconography and representations. Islamic elements became the most dominant in shaping the final metamorphosis of Malay thought and culture.

Many Malay customs and traditions have stood the test of time, serving as a source of inspiration for contemporary practices, whether in the original, modernized or evolving form, while preserving their core essence.

Roots of Malaysian Culture

Various governments or Malay Sultanates once occupied the coastal areas of Peninsula Malaysia and to date, there exists nine Malaysian states with a monarchy in place (Perlis, Kedah, Perak, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, Johor, Pahang, Terengganu and Kelantan).

The Malay people in Malaysia comprise the Kelantan Malays, Kedah Malays, Perak Malays, Sarawak Malays, Kedayan, Jakun and Temuan, as well as other groups originating from other islands in the Archipelago such as the Javanese, Minang, Banjar, Rawa, Bugis, Bawean, Bangkahulu, Kampar and Achenese.

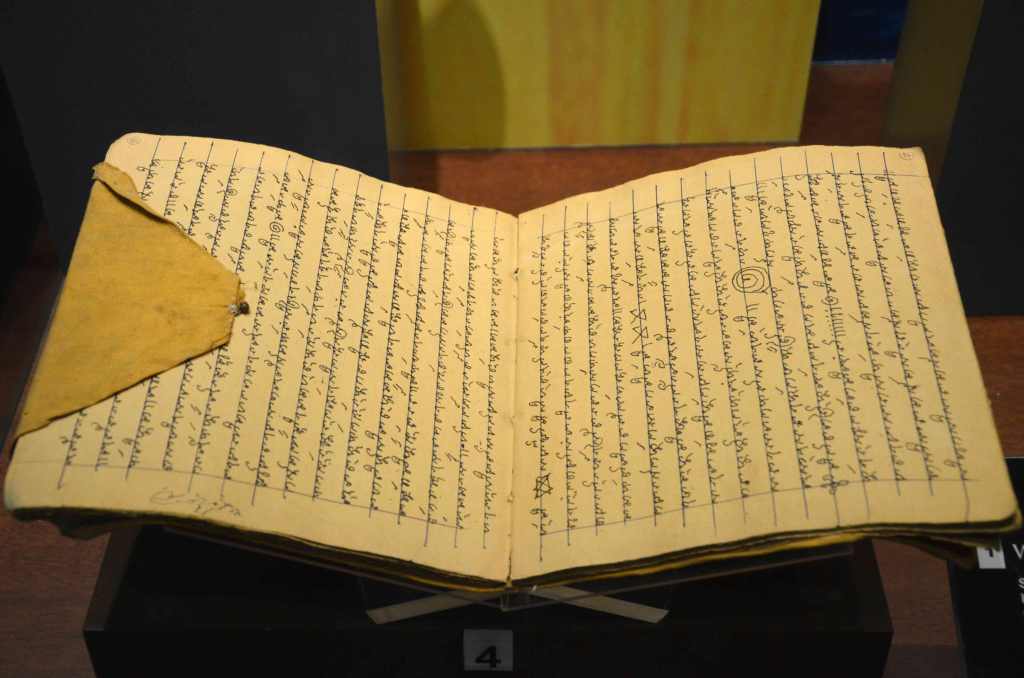

Malaysia is a successor of the Malayo-Polynesian civilisation, and its culture encompasses both physical and spiritual aspects, including tangible creations like buildings, clothing and weapons; and intangible elements like language, literary works and traditions.

Our visit began with a warm welcome from Puan Wan Noazimah Wan Kamal, Director of the MEDM. We were then guided through the museum’s exhibits by Puan Nik Maziela Idura, the Assistant Curator.

A. The Heart of Malay Culture: A Visual Exploration via Dioramas

There are six dioramas which showcase the importance of traditional crafts and deep-rooted values of family and community.

Diorama 1: Weaving and Traditional Kampung Life

The first diorama takes us to a serene Malay kampung or village, which can be seen in all parts of Malaysia particularly the rural areas. An elderly lady sits on the veranda, skilfully weaving a tikar (mat) from mengkuang leaves, used for sleeping, dining and social gatherings.

The traditional Malay house is raised above the ground to protect from floods especially for the eastern coastal areas. The space beneath the house is used to store boats; vital for transportation in riverside villages.

The kampung house features three main areas:

- The Serambi (Verandah or Front Hall) for welcoming guests and family gatherings

- The Rumah Ibu (Mother’s Room), the heart of the home

- The Dapur (Kitchen) at the rear

This diorama illustrates the architectural heritage and practical design of Malay kampung houses, which exist in harmony with its surroundings.

Diorama 2: The Art of Wau Making

The second diorama exhibits the intricate art of wau (kite) making. A skilled craftsman is seen constructing a wau using strips of bamboo, cut with a carving knife. Cut coloured paper is glued on, with designs that reflect the aesthetics of Malay art.

An important aspect of wau making is in ensuring the frame is symmetrically balanced so the wau will fly gracefully through the sky. With a distinctive head, body and tail, it symbolises a bird in flight and represents freedom and aspirations.

Each state boasts its own unique wau designs, such as the “Wau Kapal” of Selangor and the “Wau Bulan” of Kelantan. For frequent flyers, this Wau Bulan icon would be a familiar feature. Our local carrier, Malaysian Airlines’ iconic logo draws inspiration from the traditional Wau Bulan.

The diorama also features a traditional Singgora roof, originating from Thailand, featuring the cultural exchange that has enriched Malay architecture. These clay tiles are fired and placed on the rooftop to give a natural cooling effect. We see a harmonious integration of traditional building techniques with the natural environment.

Diorama 3: The Magic of Wayang Kulit

The third diorama brings us to the world of Wayang Kulit, a traditional shadow puppet theatre and entertainment. An ensemble of gamelan drums and other musical instruments fill the air as the Tok Dalang, the master puppeteer, weaves a captivating narrative.

Based on ancient Hindu epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata, the stories unfold as the carved leather puppets, mounted on banana trunks, are manipulated against a brightly lit white screen, using a kerosene lamp.

The Tok Dalang is a skilful vocal master who employs at least ten distinct voice tones to bring the diverse characters to life – heroes, villains, kings and even a jester, who adds a touch of comic relief. And this is where the magic begins, with the Tok Dalang bringing each character alive!

The diorama displays three styles of Wayang Kulit:

- Kelantanese: Characterised by puppets and manipulated with a single central stick or arm, often depicting the character riding a dragon-like vehicle. The performance begins with a symbolic gesture of waving the Pohon Beringin or Tree of Life, representing a tribute to mother nature, to start the theatrical journey.

- Javanese: Influenced by Javanese traditions, these puppets are manipulated with both hands. The character’s eyes provide clues about their nature – good or evil. They are commonly found in Johor, a state in southern Malaysia, located near the island of Java, separated by the Straits of Malacca.

- Gedek Talung: Found predominantly in northern states like Perlis and Kedah, this style reflects Siamese influences, employing a Siamese dialect and featuring puppet designs influenced by Thai aesthetics.

While traditional stories remain central, adaptations have emerged, incorporating elements of popular and current culture, such as Star Wars, Musang King and even using contemporary languages like Japanese and Korean, to connect with current audiences.

Diorama 4: A Celebration of Love: A Malay Wedding

The fourth diorama captures the vibrant and colourful atmosphere of a traditional Malay wedding ceremony. The bride and groom, adorned in exquisite songket attire, receive blessings as rose water and potpourri are gently sprinkled upon them.

The exchange of hantaran, or wedding gifts, is a momentous ritual, with the bride typically presenting trays of gifts, reciprocated by the groom at a lesser number, symbolising the greater contribution of the bride to the marriage. The offering of bunga telang flowers with hard-boiled eggs to guests, signifies fertility and good wishes for the newlyweds.

This diorama portrays the significance of customs, tradition and community in celebrating the union of two souls. The hantaran custom continues to be observed, even in modern day weddings today.

Dioramas 5 and 6: The Game of Congkak and Spinning Gasing

The fifth diorama features the traditional game of congkak. A young woman sits gracefully, her fingers moving as she plays the game on a carved wooden board. Congkak involves two players competing to collect the most seeds or marbles in their respective “homes”. In older times, holes were dug in the ground to create a natural congkak playing board.

The sixth diorama shows a man engaging in the traditional game of spinning the gasing or top spinning. Tops are also made from wood.

These dioramas depict the social and recreational aspects of Malay culture, showing how games like congkak and gasing, have not only been a source of entertainment but social interaction and intellectual stimulation. A pastime that has enriched the lives of communities for generations, it also emphasises the artistry and craftsmanship involved in developing these instruments.

B. The Vitrines: A Window into Malay Culture

Next, we explore the vitrines that showcase key themes of the Malay world.

1. Sailing and Seafaring

The different types of sea vessels

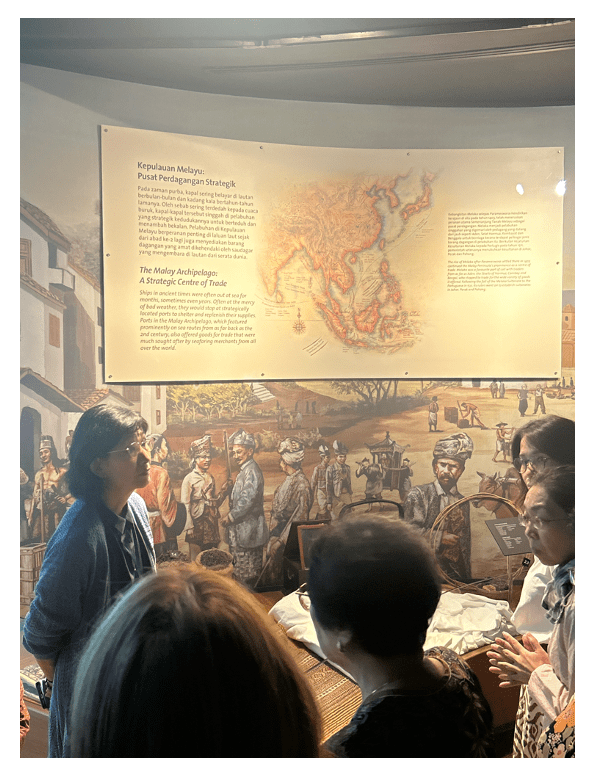

This vitrine explores the profound influence of the sea on Malay culture, evident in the concept of Motherland or Tanah Air – a connection to both land and sea. Skilled navigators, like Panglima Awang, navigated voyages by relying on the water, wind and stars, demonstrating remarkable seafaring skills without relying on compasses.

Malay boatbuilding was a sophisticated art. Vessels ranged from perahu (small fishing boats) to larger boats for deep-sea fishing and jongs capable of carrying hundreds of tons which played a vital role in regional trade. These vessels were meticulously crafted using wooden pegging, showcasing impressive engineering skill. Some of the key ports along their seafaring routes included Aceh, Padang, Palembang and Banten.

The vitrines reveal fascinating details. A wooden box, likely made from cengal or alternatively jackfruit wood, holds hooks, gadgets, knives and even a first aid kit. Carvings of rice grains and flowers adorn the box. Next to it, is a utility box in rectangular shape which also functions as a seat and a food box which is round in shape, possibly designed for the royalty, as it features intricate decorations.

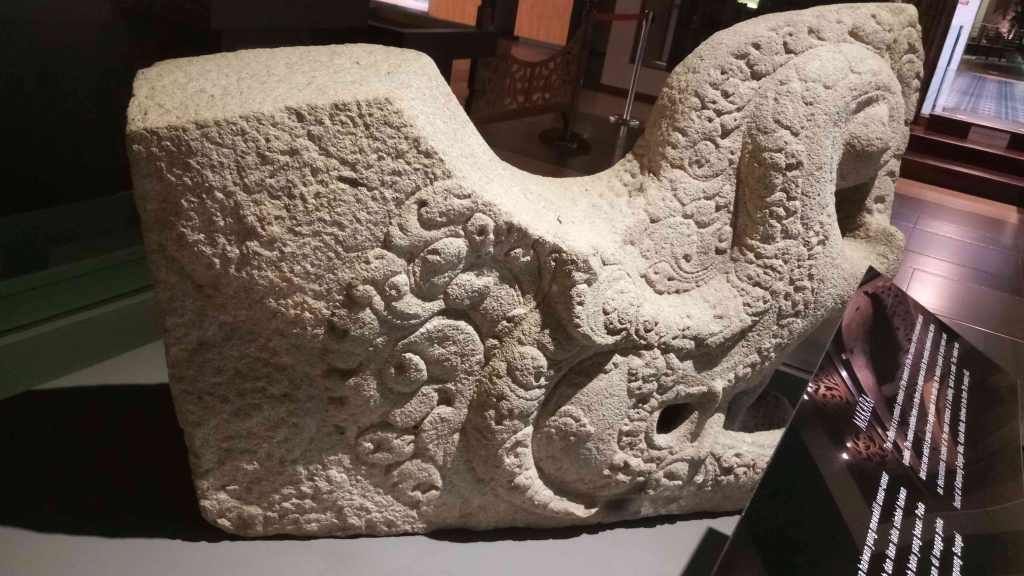

Motifs adorning the vessels

Cultural influences, from early indigenous beliefs to Islamic symbolism, are evident in the ornate carvings and mythical motifs adorning the vessels. We see the heads of boats ornamented with bangau (stork), okok and also makaras (mythical sea creatures). Historical accounts from China and the Netherlands attest to the scale and sophistication of Malay maritime activities.

2. The Sound of Music: Musical Instruments

Musical instruments explained

Musical instruments in the Malay culture were significantly influenced by Arab merchants who arrived in Melaka. These instruments were assimilated and found their place in various ceremonies, including weddings, the coronations of Sultans and Kings and traditional performances.

- The gendang is a drum made from animal skin, played with hands or sticks. It comes in various sizes and types, including single-sided and double-sided drums. Gendang are commonly used in ceremonies and cultural events.

- The kompang is a drum made from cow skin and was traditionally used to gather local people’s attention to their wares during trade activities.

- The rebab is a bowed string instrument, originally from the Middle East but became prominent in Malay music. It is worth noting that the rebab tunes were likely influenced by interactions among traders at various stopovers along a combination of maritime and overland trade routes.

- The gambus is a plucked lute from the Middle East, popular in Malaysia. It has 3-12 strings and a distinctive half-pear shape. It’s often used for entertainment, accompanying zapin dances and ghazal singing.

- Gong comprises large and small gongs, the integral components of gamelan and Wayang Kulit performances.

- The angklung is a traditional Indonesian bamboo instrument that produces sound when pulled and shaken at the bottom and often played in groups, accompanying dances like Kuda Kepang and Barongan.

- The serunai or flute is a woodwind instrument with Sumatran roots from Minang immigrants, often played during weddings, pencak silat martial arts and wayang kulit shows.

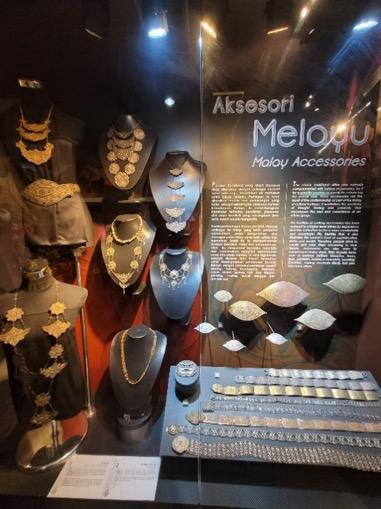

3. Malay Accessories and Ornaments

Malay Accessories

This section showcases selected elements of traditional Malay accessories and ornaments:

- Pending cutam: These are traditional buckles used in Malay attire, with the silver pending featuring ornate floral motifs worn by women, often indicating high social standing. The nielloware pending is used as a buckle for men’s silver belts and are crafted with ornate floral designs and the use of gold.

- Artisan Jewellery Brooch: The three-piece brooch holds symbolic or cultural significance, perhaps related to status or lineage.

- Caping: A silver protective covering functioning like a modesty cover for genitals worn by young children under the age of three, common among wealthy Malay families on the East Coast. These were associated to fertility beliefs or protection, reflecting religious and cultural practices.

- Pillow-End Plates: These decorative items, stitched with silver and gold-plated thread, further highlight the emphasis on aesthetics and wealth within the upper classes.

These accessories, along with their intricate designs, reflect the social stratification of the time, where access to fine clothing and adornments were often reserved for the wealthy.

4. Traditional Costumes

Malay attire reflects trade and cultural exchange, evident in the use of fabrics like Chinese Silk and Indian Petola. Songket, a prestigious woven fabric with intricate gold or silver threads, is particularly prominent in Kelantan and Terengganu.

Various traditional clothing styles, including Kebaya Labuh, Cik Siti Wan Kembang, Baju Kurung Teluk Belanga and Cekak Musang, each have unique characteristics and regional associations. Overall, Malay attire showcases the enduring influence of cultural traditions and craftsmanship.

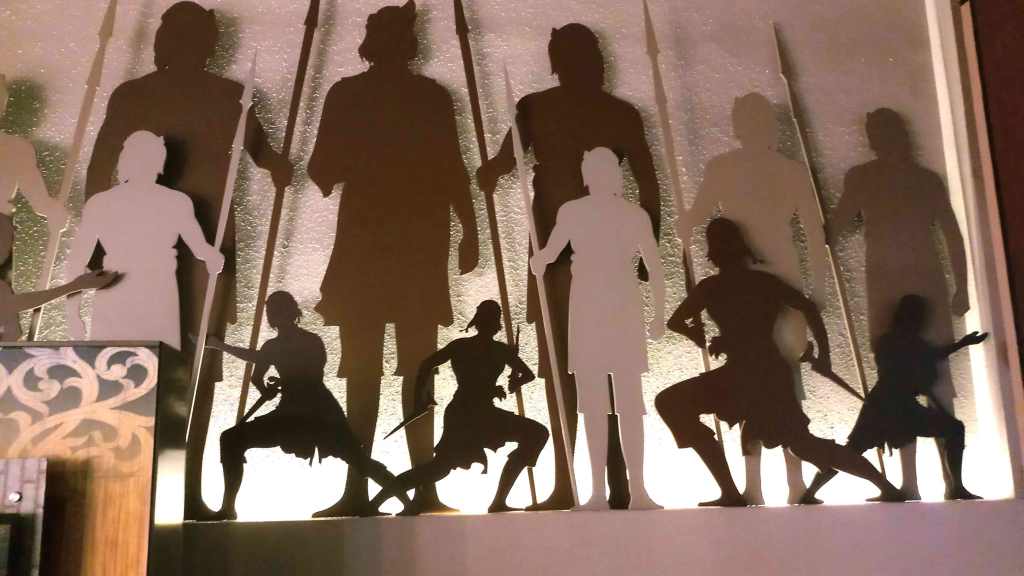

5. Weaponry: Malay Arms and Armour

This exhibit showcases the martial traditions of Malay society through a display of weaponry, including cannons, short weapons and long weapons.

- Cannons: Originally from Sumatra, these weapons were designed for portability and warfare. Smaller versions were even used as wedding gifts in Brunei.

- Short Weapons: The most notable is the Keris, a traditional dagger with a head, body and sheath. It served as a status symbol and weapon

- Long Weapons: The exhibit includes the tombak and the lembing, both types of spears used in warfare.

The Palace’s strict monitoring of weapons’ production highlights the importance of controlling weaponry within the royal court to maintain social order.

6. Utensils

Traditional Malay utensils

Traditional Malay utensils, often crafted from metals like silver and brass, are adorned with niello, a technique of inlaying metal. These functional pieces such as moulds for putu, bahulu and kuih kapit or love letters, hold cultural significance and evoke nostalgic childhood memories.

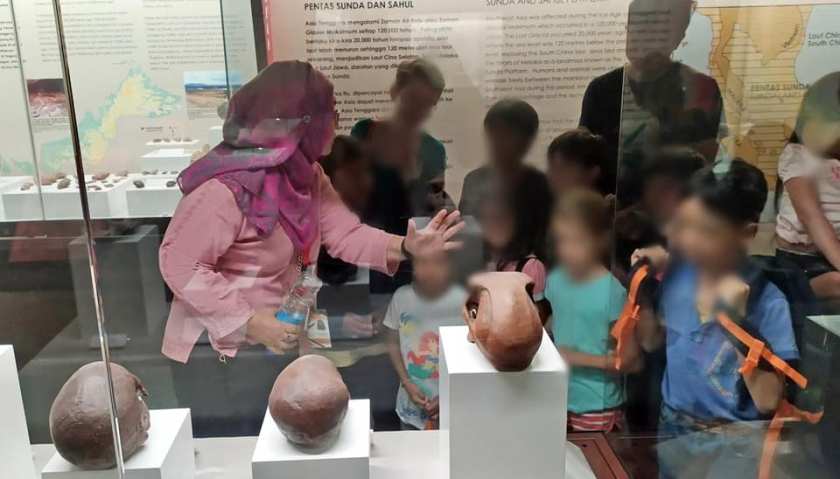

7. Pottery

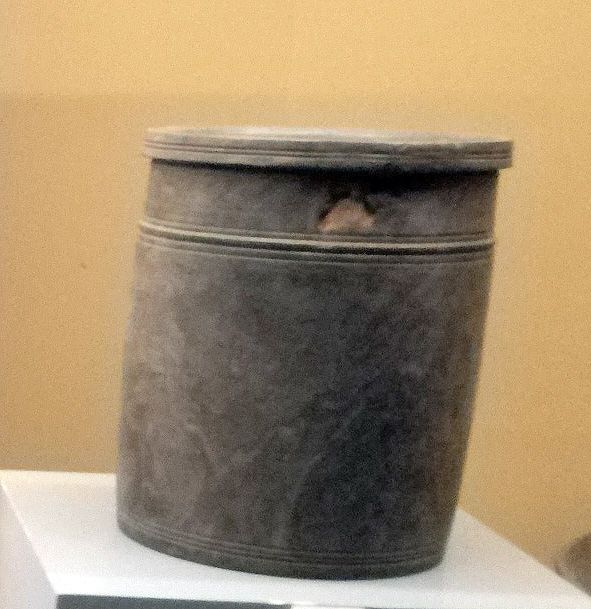

Pottery is a traditional Malay craft with key production centres in Kelantan, Kuala Kangsar, Pahang and Sarawak. One of the better-known pottery products is the Labu Sayong, used to store cool drinking water. It’s made from processed clay, shaped and fired to increase its durability and water resistance. The design of pottery often reflects its intended function.

8. Brassware

Malay brassware, a testament to skilled artisans, particularly in Terengganu, plays a vital role in Malay culture. From ornate ceremonial pieces used in royal courts such as betel leaf boxes, trays and tiered serving dishes, to functional household items like kettles, pots and decorative lamps, brassware reflects the rich Malay heritage and artistic traditions.

9. Nielloware

Nielloware, a luxurious silverware from southern Thailand, was traditionally used by royalty. Crafted from silver alloy often with gold, it features elaborate designs. It is common especially in Kedah, Kelantan, Perak and Pattani. Nielloware items include bowls, jars and accessories.

10. Silverware

Malay silversmithing, with a history rooted in royal patronage, produced exquisite items for both ceremonial and everyday use. From ornate royal regalia like sceptres and crowns to functional household items such as betel containers, trays, teapots and even decorative items like jewellery and hairpins, these silverwares often feature refined designs, reflecting the wealth and status of their owners.

11. Woodcarving

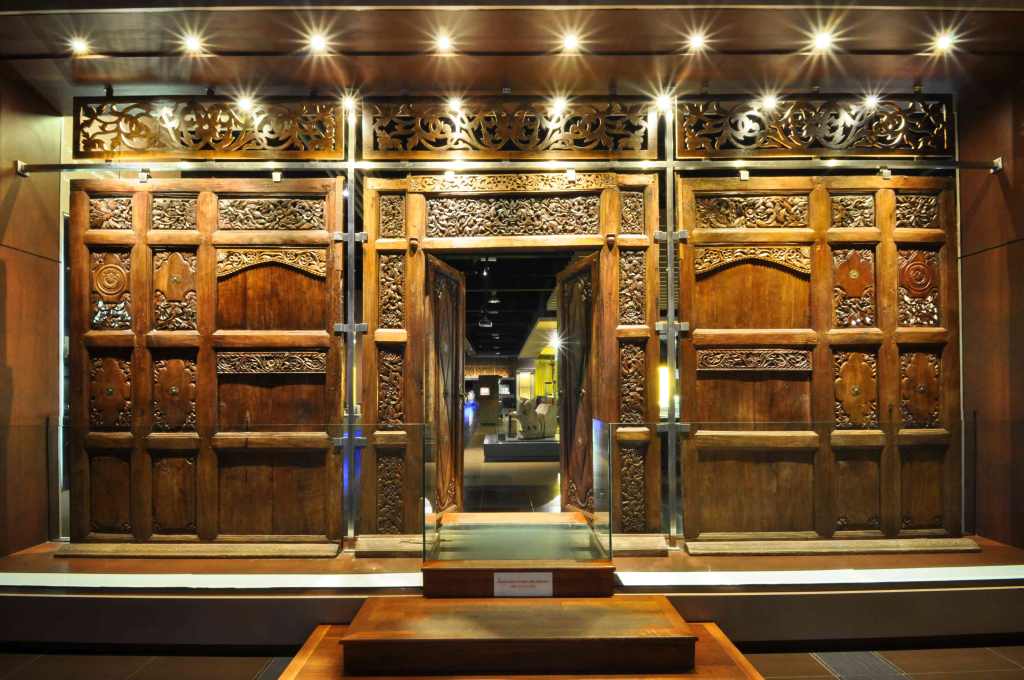

Malay woodcarving is a significant cultural art form, characterised by delicate designs inspired by nature, religion and philosophy. Skilled artisans utilise techniques such as ukiran timbul (raised carving) and ukiran tebuk tembus (perforated carving) to create stunning works of art.

These carvings adorn palaces, homes and religious structures, often featuring motifs like floral patterns, calligraphy and geometric shapes. Examples include ornate door panels, intricately carved window frames and decorative elements on furniture and household items.

Summary

The Malay World Ethnology Museum offers a captivating journey through the heart of Malay culture, providing valuable insights into the rich heritage, traditions and artistic expressions that define this vibrant civilisation. Through a combination of dioramas, artefacts and informative displays, the museum effectively communicates the legacy of Malay culture.

Visitors are encouraged to visit and immerse themselves in the museum’s diverse exhibits. This allows them to connect with the past, link to the present, and reflect on their own experiences, to gain a deeper understanding and appreciation of Malay values and traditions.