by Afidah Rahim

The Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia (IAMM) has an extensive collection of Malay Qurans, from which two samples will be examined here. Malay Qurans are only ornately decorated at the beginning, the middle and the end. Considering that my previous blog article had highlighted the illuminated pages found at the beginning and end of Malay Qurans, this article features the central illuminations instead. In his forward to Al-Quran: The Sacred Art of Revelation Vol. II (2014), the Chairman of IAMM invites us to contemplate the beauty of both the meaning and physical appearance of these manuscripts. This is because embellishment of the Malay Quran is done to assist recitation and to bring forth emotions, for Muslims believe the Quran relates specifically to the heart of man. Hence, building on ‘The Quran and the Sunnah’, we will briefly touch upon tafsir (Quran exegesis) of the central illuminated pages.

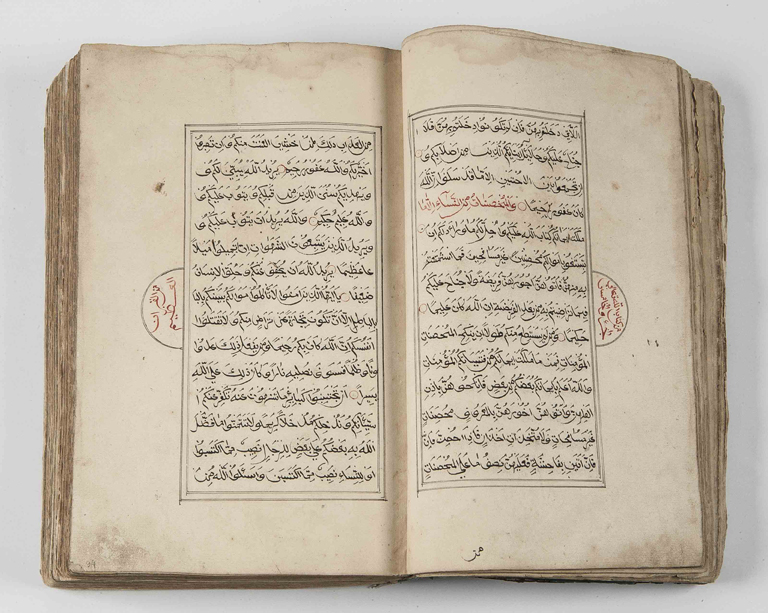

Malay Qurans are sometimes decorated in the middle, possibly influenced by Uzbek, Kashmiri and Indian Qurans. This is done to celebrate the reader’s arrival at the halfway point – the ‘heart’ of the holy text. The decoration style is similar to the front and back pages. A Javanese Quran, for example, could feature batik-style motifs throughout its illuminated pages. Different scribes and illuminators may use different methods to indicate the centre e.g. letter, verse, surah or word count. According to the tradition of Quran reading in the Malay world, the word ‘wa-l-yatalattaf’ in Surah Al-Kahf verse 19 is accepted as the centre word of the Quran. This translates to ‘and let him be careful’ that means to conceal himself as much as possible. Malay Qurans, like Terengganu Quran 2012.13.6, may emphasise this word with enlarged or gilded script to mark its midpoint.

As far as illumination is concerned, Surah Al-Kahf (the Cave) can be said to be the central marking. Both the Malay Qurans featured here are illuminated at the start of Surah Al-Kahf. With reference to Tafsir ibn Kathir, Al-Hakim recorded from Abu Said that the Prophet (s.a.w) said “Whoever recites Surah Al-Kahf on Friday, it will illuminate him with light from one Friday to the next”. Tafsir ibn Kathir is the most widely accepted explanation of the Quran, based on other parts of the Quran itself as well as hadith i.e. ‘tradition’ referring to the narration, account and record of actions and sayings of Prophet Muhammad (s.a.w.).

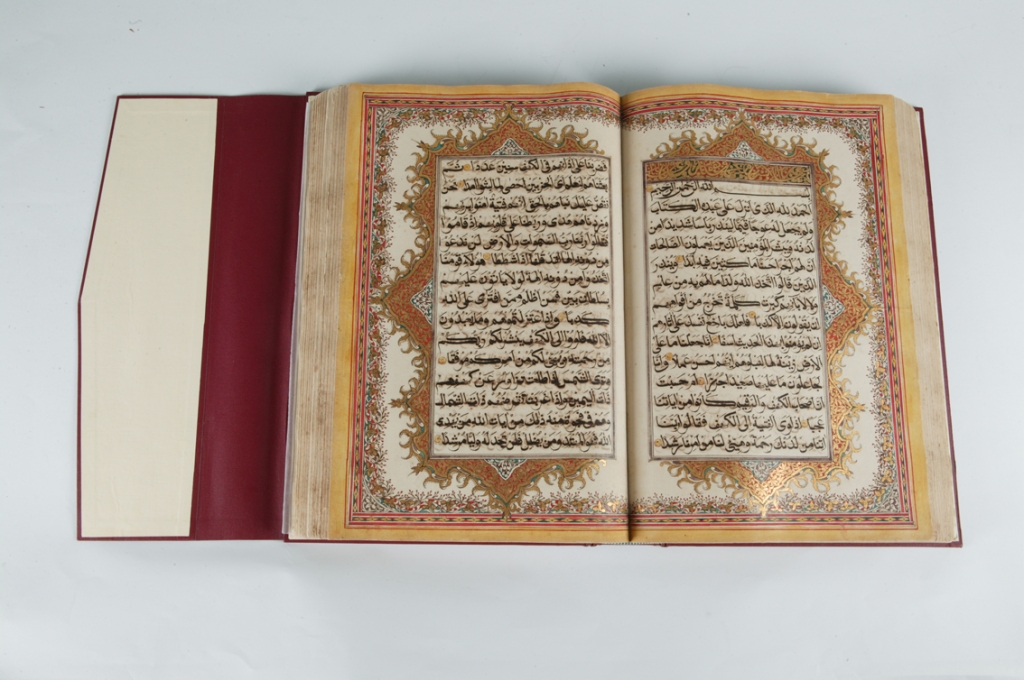

Our first artefact is a Royal Terengganu Quran 1998.1.3427 dated 1871CE/ 1288AH. It is considerably large, measuring 43cm by 28cm and uses naskh script for clarity. Terengganu style is deemed the finest and most delicate of Malay Qurans. This artefact would have been copied during the reign of Sultan Baginda Omar (ruled 1831; 1839-76) who attracted foreign students and artisans to Terengganu by encouraging learning and industry. Foreign artisans then passed on their skills to the locals.

Malay Qurans have rich and symmetrical decorations. Both our artefacts have double-decorated frames illuminating the central pages. Similar to Malay woodcarving, these decorations include sulur-suluran (vegetal scrolls) and gunungan (mountain-shaped) motifs. Arabesques and geometric designs from the broader Islamic world are complemented with the permissible plant-motifs; avoiding figural representations. The arch-shaped gunungan motif is a legacy from the region’s Hindu past, which continued into the Islamic era since it reflects the natural landscape.

Colours too were produced from nature. The most popular colours used on Malay Qurans were red (from brazil-wood), black (from soot or charcoal) and yellow (from turmeric). Our Terengganu Quran features much gold, traditionally reserved for royal patronage.

In Southeast Asia, copying the Quran was only entrusted to professional, religious scribes. These scribes were occasionally under the supervision of a royal atelier. The design of our Royal Terengganu Quran suggests a foreign artisan. The clues lie in the noticeable use of lapis lazuli blue along with non-local choice of floral and vegetal decorations. Lapis lazuli was imported from Afghanistan or China and was no doubt an expensive pigment. Nonetheless, typical of Terengganu style, there is an outer frame i.e. a border running along the exterior edges with curved corners.

The central pages here include verses 1 to 17 of Surah Al-Kahf. It is noteworthy that some Qurans have abridged tafsir annotations written in the white margins of the illuminated pages, even though such is not the case here. The main theme of this surah is letting go of materialism. It begins with praise to Allah for sending us the Quran. The first passage warns of great trials ahead but gives glad tidings to the believers. Subsequently, the story of the youths who fled to a cave is told. According to Tafsir ibn Kathir, these youths were sons of Byzantine leaders who lived under a tyrannical king called Decianus, who tried to dictate their religion. Refusing to believe in multiple gods, these youths hid in a cave and they were protected by Allah. In other words, the youths defied worldly authority to guard their tawheed (belief in the one and only God) and they were thus saved from persecution.

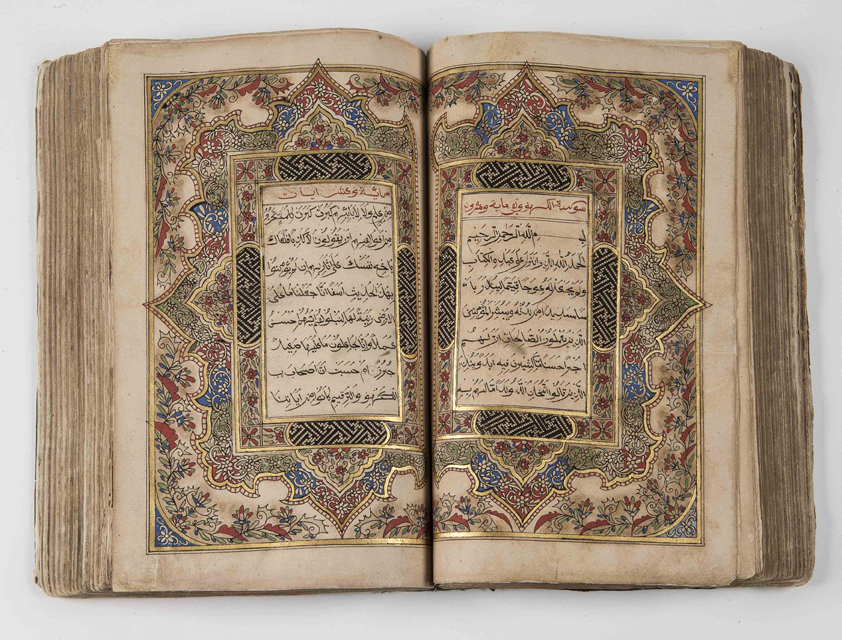

The central illumination of our second artefact, Quran 2004.2.3, also includes an outer frame with curved corners, which is unusual for Javanese Qurans. This Quran measures 30cm by 20cm and is therefore, smaller than our first artefact. Our Javanese Quran displays similar motifs to the Terengganu Quran including gunungan, floral and vegetal scrolls. In addition, this artefact shows an interlocking black pattern within its innermost frame, known as ‘banji’, suggesting its Cirebon (West Javan) origin. In Javanese Qurans, the banji (swastika) motif derives from the island’s Hindu-Buddhist history and is present because it resembles the regional craft of rattan weaving.

This Javanese Quran uses red, gold and black, along with a more striking blue. Blue is more prominent in Javanese Qurans in a variety of shades including indigo to light sky blue. The surah headings are in red thuluth script while its text is in black naskh. The European paper watermark shows a lion within a roundel, topped off by a crown, which dates this Quran to the 19th century CE. Synthetic (French) ultramarine as a substitute to lapis lazuli was available during this time, which may have been used here.

The illuminations here surround verses 1 to 9 but one word of Surah Al-Kahf. The word ‘al-kahfi’, which gives the surah’s name, occurs in verse 9. With the addition of verse 10, the illuminated pages and missing word ‘ajaban’ (wonders) would protect its reader from the false messiah. Referencing Tafsir ibn Kathir, Imam Ahmad recorded from Abu Ad-Darda’ that the prophet (s.a.w.) said, “Whoever memorizes ten ayat from the beginning of Surah Al-Kahf will be protected from the Dajjal”.

It is now clear that these central pages hold particular benefits for the Quran reader. Surah Al-Kahf is appropriately illuminated since spiritually, its reader can be illuminated with light for up to a week. The illuminated pages are indeed arresting amidst the normal pages of text. Nonetheless, even the normal pages may have ornamentation at regular intervals along the margins to indicate the reader’s position within the holy text e.g. juz’ or nisf markers. Both artefacts showcased above represent the exquisite craftsmanship and artistry of nineteenth century CE Malay manuscripts.

References

The Noble Quran translated by Dr Muhammad Taqi-ud-Din Al-Hilali and Dr Muhammad Muhsin Khan (1997) Riyadh: Darussalam

Abdullah Zakaria Ghazali (2011) Terengganu Sultanate, The Encyclopedia of Malaysia, The Rulers of Malaysia Vol. 16. KL: Editions Didier Millet

Gallop A.T. (2012) The Art of the Malay Quran. Arts of Asia. Jan-Feb 2012

IAMM (2020) Mirrors of Beauty. KL. IAMM

IAMM (2016) Introduction to Islamic Arts – Calligraphy. KL: IAMM

IAMM (2014) Al-Quran: The Sacred Art of Revelation Vol. II. KL: IAMM

IAMM (2008) Malay Manuscripts: An Introduction. KL: IAMM

IAMM (2006) Al-Quran: The Sacred Art of Revelation. KL: IAMM

Natasha Kamaluddin (2020)The Halfway Point. KL: Natasha Kamaluddin

Rajabi Abdul Razak (2009) The 19th Century Malay World Qurans in the Collection of IAMM. An Application and Analysis of the Colourants.

Ros Mahwati Ahmad Zakaria (2005) Manuscripts: The Word Made Manifest. The Message and the Monsoon, KL: IAMM

IAMM gallery storyboards & Wikipedia

IAMM curator – Dalia Mohamed